An article from Norwegian SciTech News at NTNU

Beer and a calf’s head yield gold and silver

Scientists striving to recreate the 500-year-old technique of mint masters found their solution in a boiled calf’s head and good beer.

Were mint masters in 16th-century Trondheim able to make their own equipment to determine how much silver their coins contain?

“If it’s simple enough for us to figure out, the coin masters of 500 years ago no doubt could do it too, because they were professionals,” says NTNU’s professor emeritus Otto Lohne. Lohne and engineer Paul Ulseth have recently been testing their goldsmithing and minting skills, simply because they are curious.

The two researchers have even crafted their own bone-ash cups, or cupels, from animal bones. These bowls were an important piece of equipment in the early mint masters’ work.

They’ve also made two different metal alloys to test the old method on. One mixture is a gold alloy consisting of gold, copper, and silver. The other is a silver alloy.

They already know the silver, gold and copper content in their test compositions. Now they’ll see if they can achieve accurate measurement results using the old method.

Collaborating with a jeweller

Even today, jewellers use a variation of the old method to ascertain the gold and silver content in mixtures of metals.

“This is a well-known method,” says experienced goldsmith Helge Karlgård.

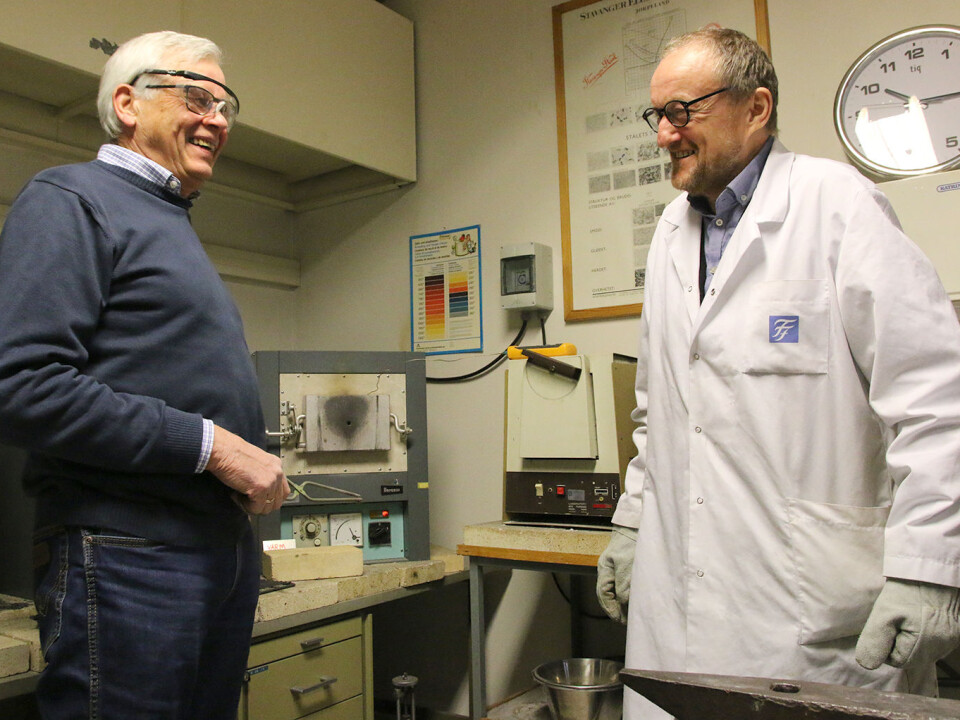

But Lohne and Ulseth aren’t content to use the modern variation on the method. The researchers have therefore teamed up with Karlgård to see if they’re on the right track. He came with gold and silver alloys and joined them on NTNU’s Kalvskinnet campus in Trondheim to follow along as the researchers try out the old method.

“Do you think it will work ?” the researchers ask Karlgård.

Discovering mint workshops

In the 1990s, archaeologists conducted excavations at the Archbishop’s Palace in Trondheim. There they came across workshops that minted coins in the 1500s.

The production of coins included very clear and very strict requirements for how much silver coins should contain. So coin masters had to know how to measure, or assay, the metal they used.

In the Archbishop’s Palace, the archaeologists’ finds included 200 used cupels made of bone ash. These cupels, which you can see pictured, were porous bowls that goldsmiths and coin masters used when they analysed the composition of the precious metals contained in alloys. (See fact box.)

But was the coin master in the Archbishop’s Palace able to create these cupels himself, or did he import them?

Beer and calf

The researchers wanted to find out. To do this, they had to clean and burn a calf’s head. The forehead bone is reputed to be the best part of the calf for making the bone-ash cupels.

“I boiled the head on my patio,” says senior engineer Ulseth, and Lohne burned the bones in his woodstove one day when his wife was away.

The fired bones were broken into pieces, crushed and sifted three times before being washed and dried. Despite many opportunities to make mistakes in the process, Ulseth and Lohne successfully produced the bone ash.

Then they had to figure out which beer to use. According to the old recipes, beer is used to lightly moisten the bone ashes, so that the ash can be formed into a bowl in a device specially designed for the task. The beer binds the ash. Not too much moisture. Not too little.

They concluded that bottle-fermented beer was the right choice. The law prevents us from telling you exactly which beer the researchers used, but if you’re tempted to replicate the process, you can find a full description here (in Norwegian): Fremgangsmåten med kontakter.

“The cupels look good,” says Karlgård, who is happy with the final products Lohne and Ulseth have pounded and pressed into shape.

Apt learners

Ulseth is the senior engineer at NTNU’s Department of Chemistry and Materials Technology. Lohne has been employed at NTNU since 1980 and is connected to the Department of Materials Science and Engineering. These are no beginners.

But even with their deep academic background, they are apprentices in this context. As compensation, they are apt learners.

“This is one of the oldest methods for determining the chemical composition of metals,” says Lohne.

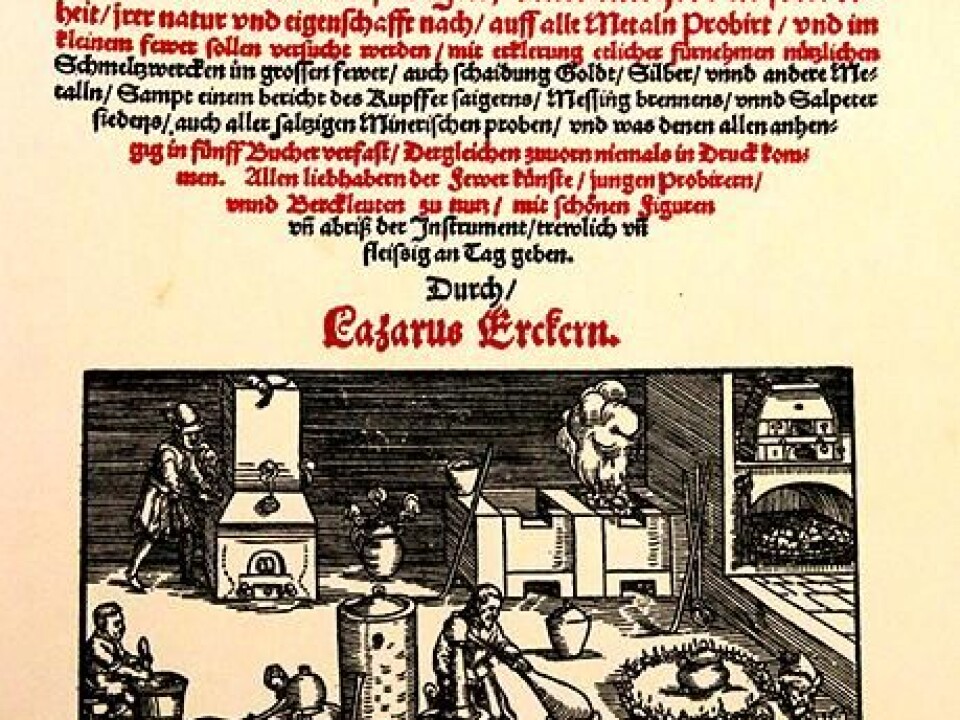

The researchers found several old recipes on how to produce bone-ash cupels, but they have selected one recipe from the book “Treatise on Ores and Assaying” by the Saxon and Bohemian coin master Lazarus Ercker from 1574.

“The more we worked on this, the better we understood the drawings,” said Ulseth.

The researchers used trial and error where the instructions weren’t entirely clear. For example, they tried to dry the cupels in the furnace, but that didn’t result in the right consistency. Probably the cupels dried too fast. Storage at room temperature for a week gave better results.

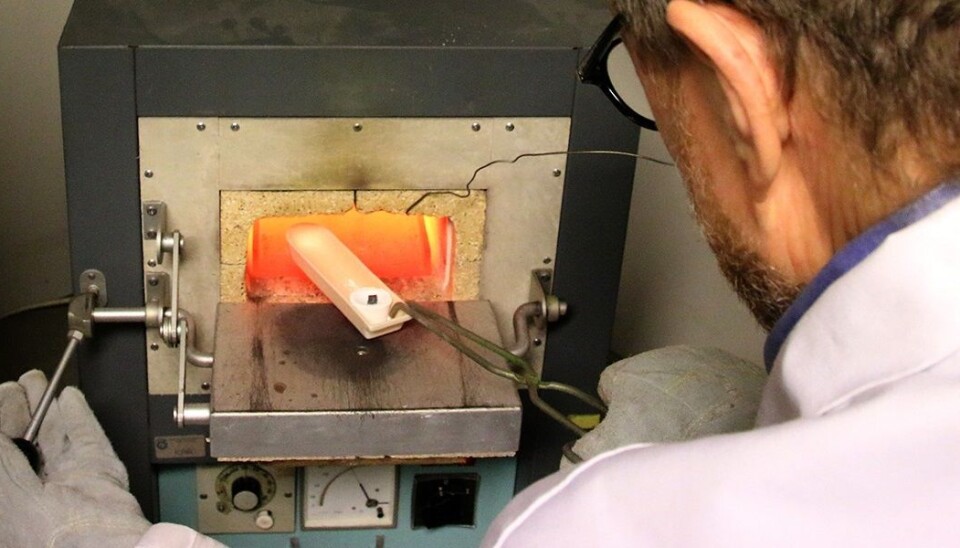

Into the furnace

The furnace temperature is up to 918 ° C. Lohne and Ulseth have set two cupels into a bowl. They added the silver sample and 10 times as much lead to one cupel, and to the second cupel a mixture of gold alloy and lead. They insert the dish with the cupels into the oven.

“Lead melts fast, at less than 350 degrees,” says Lohne, who knows perfectly well that the precise melting point is 327.46 ° C. The other metals melt at much higher temperatures.

As the samples heat to 900 ° C, the gold and silver retain their elemental form while the lead oxidizes. This lead oxide melts at 888 ° C and is drawn into the cupel’s porous bone ash by capillary action. The precious metals remain in the cupels, silver in the one with the silver alloy and a mixture of gold and silver in the other.

At least, this is how the process should go if Lohne and Ulseth have done all the steps correctly.

They peek into the furnace a few times during the heating. A glowing bead of the precious metals forms in the bottom of each cupel. Around them the bone ash starts to change colour as the lead oxide is absorbed.

After only a few minutes, it’s time to take out the bowl with the cupels. Eagerly, the researchers examine them and can conclude that beads look better than during the first trials. Ulseth places the cupels under the microscope. He loosens the precious metal beads and readies them for weighing.

The results

Before melting the silver mixture, the researchers added 0.15 grams of alloy 925, which refers to a purity of 925 ‰. This was mixed with 1.40 grams of pure lead.

After cupellation, the resulting bead weighed 0.14 grams. A little quick figuring yields a silver content of around 933. The small discrepancy is probably due to some impurities from the cupel surface on the underside of the small bead.

Into the gold mixture they added 0.18 grams of alloy 585, which in this case means 585 ‰ gold and 166 ‰ silver. This was mixed with a 1.59 gram lead plate.

After cupellation, the bead weighed 0.14 grams. This means that the silver and gold content is around 778 ‰. Also this bead had some impurities on the bottom, which explains the deviation from the perfect result, which would have been 753 ‰.

“Does this pass the test?” Karlgård is asked.

“Yes, very much so!” the jeweller replies.

Coin masters used same approach

So, could the mint master at the Archbishop’s Palace actually do this, too? Yes, say the researchers, who have now summarized both the process and their conclusions.

“It’s highly likely that the coin master had access to everything he needed to manufacture good cupels and was able to carry out the cupellation with dependable results,” they conclude in their summary.

The researchers have no doubt that coin masters in the 1500s had all the necessary ingredients, the technical tools and stoves that reached a high enough temperature. And Lohne and Ulseth could probably have found jobs if they had lived 500 years ago.

“So we got it to work! exclaims a clearly pleased Lohne.

Yes, they did.