An article from NVE - Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate

World’s most claustrophobic lab

Two hundred metres below a Norwegian glacier, researchers take samples while the laboratory melts slowly over their heads.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

In a tunnel system in the mountain scientists have direct access to the bed of the glacier, under 200 metres of glacier ice. However, they need to work quickly because the extreme pressures at the bottom of the glacier gradually shrink the tunnel as they work.

"The glacier laboratory provides a unique opportunity to do glacier research while actually inside the glacier," says Miriam Jackson at the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE).

"This gives us new information about how glaciers move and helps us to fill in the gaps in our knowledge about the impact of climate change on large ice sheets such as Greenland and Antarctica," she says.

She describes how the glacier laboratory provides direct access to the base of the glacier, where the ice meets the rock.

Here they can set out instruments or take ice samples without first drilling through several hundred metres of ice, which is how they would normally do this type of work. The instruments can be left in place to collect data for days, weeks or even years with fairly easy access for downloading the data and for maintenance.

"The ice samples that we can get are not disturbed by atmospheric processes," she explains. "It is also much easier for us to get these kinds of samples than for scientists who drill for ice cores in Greenland, for example, where the diameter of the drill limits the sample size."

In the glacier laboratory scientists can test theories and models, making it an important part of Norwegian and international research infrastructure. The research findings also provide new knowledge that can be used in industry, such as power generation from sub-glacial water intake and climate effects on energy production from glacier runoff.

It’s also possible to perform research that can be used for modelling the ice dynamics of small glaciers, for developing technology for the search for life on small icy planets and moons, and for the underground storage of nuclear waste.

The glacier laboratory is owned and operated by the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE).

NVE is the national centre for expertise in hydrology and has measured the mass balance of Norwegian glaciers since 1949. The laboratory was established in 1992 during excavations for tunnels for a large hydroelectric plant.

Shrinks to half size in one day

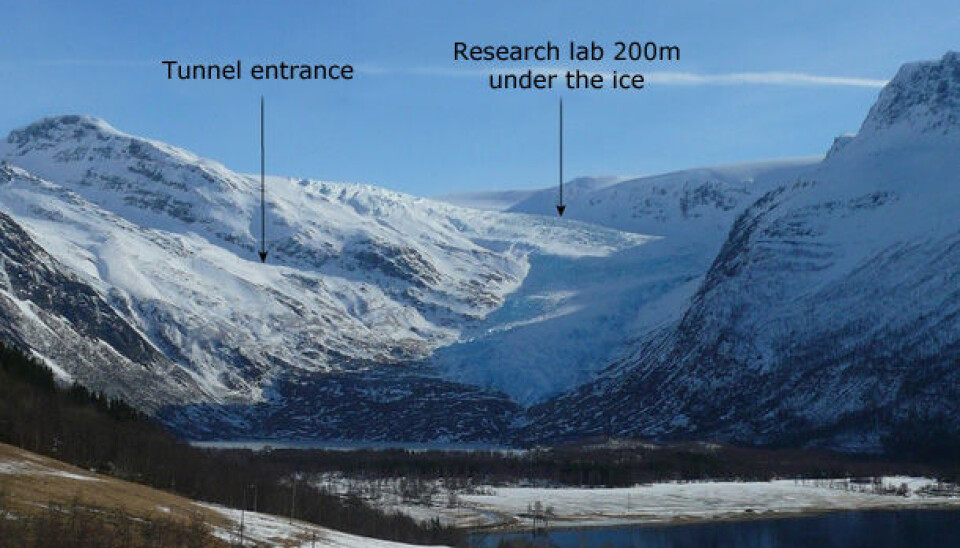

The laboratory is not the kind of place where you can just drop in. Normal access is by boat and then by foot to the tunnel entrance some 500 metres above sea level or by helicopter.

The opening to the ice itself is usually closed with steel beams that are removed when researchers need access.

Research activity takes place mainly in the winter when there is little water under the glacier.

To access the base of the glacier, researchers must use fire hoses with hot water to melt an opening in the ice. Scientists then have a tunnel that is about 2 m high in which to work. However, after the tunnel has been melted out researchers must act quickly because it shrinks to half its size each day.

For security reasons, tourists are not allowed in, but exceptions have been made for various television crews.

In extreme company

In an informal poll conducted by Science Illustrated in 2011, Svartisen subglacial laboratory was declared the world's most claustrophobic laboratory.

Together with a number of other laboratories in special locations, it was presented under the title "Extreme laboratories."

Miriam Jackson does not think the award as the worlds most claustrophobic was undeserved.

"It can feel rather strange to know that while you are working deep in the ice tunnel the weight of the glacier above is gradually shrinking the tunnel. If you are not careful and keep one eye on the time, then you can end up being trapped in the ice", she says.

She hastens to add that all researchers have come safely out again.

-------------------------------------------------------

Read the article in Norwegian at forskning.no