This article was produced and financed by The Norwegian School of Sport Sciences - read more

Oslo Marka Forest: the story of the city residents’ refuge and playground

The Oslo Marka Forest transformed from a agricultural area for the few to a wilderness park for the many. As the public’s perception of the forest changed, so did the physical landscape.

It is said that Oslomarka – the forested and hilly areas surrounding Norway’s capital – makes Oslo unique, with its vast forested areas both within and right on the city borders.

The term marka connotes a landscape that is either wilderness or to some extent cultivated for agricultural use but still strictly zoned as non-residential.

But how long has Oslomarka actually existed, out there in the forests? In many ways, it was not until the interwar period that the people of Oslo became aware of Oslomarka and that the area became a part of their surroundings. With time, a modern recreational area emerged.

Iver Mytting recently defended his doctoral dissertation entitled The forest’s ‘blue blazes’ – The emergence of Oslomarka as a recreational area – describing the creation of Oslomarka, and the people and factors that played important roles in this transformation, from an extensive area of forestation to a park.

History in progress

This transformation came about by means of several processes occurring on parallel. One of these was the establishment of several new organisations for so-called friluftsliv, outdoor pursuits, in the 1920s, such as the “Frilufts-klubben” (Outdoors club) and the “Foreningen til fremme av friluftsliv og kropskultur” (Association for the promotion of outdoor pursuits and physical culture).

The Norwegian term friluftsliv isn’t just about being outdoors, it can be defined as “physical activity in open spaces during leisure time to experience diverse natural environments and foster experiences of nature”.

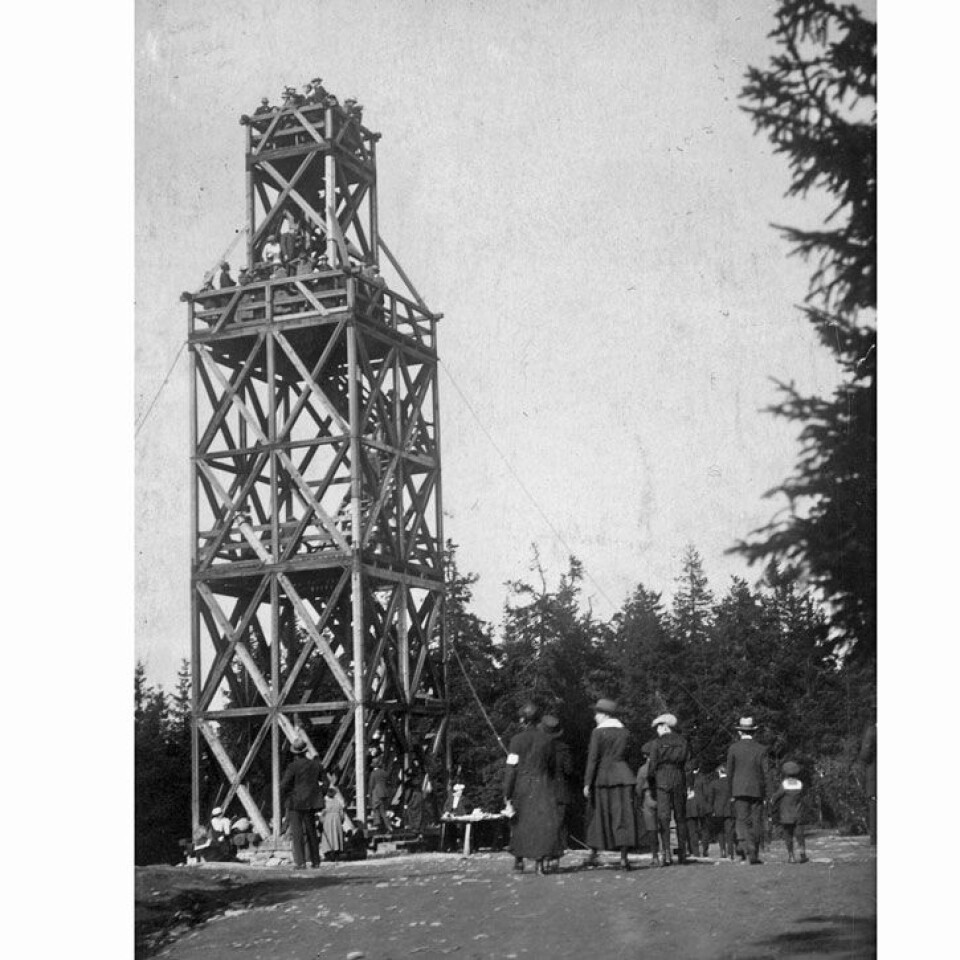

These new friluftsliv-organisations discovered new areas in the forests and wanted to share their “discoveries” with the general public. They told stories and displayed photographs of beautiful spots and wonderful adventures, printed in magazines.

“Throughout the interwar period, these stories from Oslomarka grew in number, with an increasing level of embellishment. All these descriptions made Oslomarka what it is, it attracted people to visit and presented the landscape to the world at large”, says Mytting. “Oslomarka was literally picked up and transported outside its borders into people’s homes.”

On a parallel with this, the outdoor pursuits organisations and forward-looking individuals helped make Oslomarka national property. The forests acquired a new role as an area for walking and recreation, as a park.

But none of this would have been possible unless the people could afford it, and they were not able to afford it until the interwar and post-war period. Iver Mytting explains that new regulations governing working hours were introduced in 1919 with the Act relating to leisure time, and this played an important role also.

“It is relatively easy to interpret the increase in written descriptions of Oslomarka as, quite simply, evidence of some underlying growth in interest. But these texts can also be interpreted as a force in themselves. The view that the landscape has been shaped by the texts written by these friluftsliv organisations.”

Blue blazes

In Iver Mytting’s dissertation, which he himself describes as a hypothesis on an historical development, he writes that these written descriptions can also include waymarking and preparation of maps with new routes. Waymarking is the creation of links to and in the landscape – the landscape is organised by means of characters, language and routes, and gains a whole new infrastructure.

“This new practice helped shape Oslomarka. When the outdoor pursuits organisations wanted to start describing routes through Oslomarka in the 1920s, they quickly found that it was not enough to write things down and draw them on paper. They also had to create a number of symbols on the ground. Without signposts and the blue blazes on the trees, the route descriptions would be practically impossible to write, or follow”, he says.

Iver Mytting explains that the focus point for his dissertation has been this closely interwoven link between what has been written down on paper and the symbols on the ground, and that he has studied how this has contributed to changes in the landscape.

He believes that these not only helped visitors find their way in the forest, they also provided a completely different view and new perspective of nature.

“What’s more, this infrastructure was a connecting link for the landscape, and played a final, decisive role in determining what belonged to and what did not belong to this unit of land that emerged and was subsequently named Oslomarka.”

Purchased Oslomarka as a national property

But Oslomarka is not really a park, so why does Mytting use this word?

“My dissertation describes the historical links between the phenomenon of a park and Oslomarka,” explains the researcher.

Today, most people probably think of Oslomarka as a natural area of countryside, but it is also – at the same time – a cultural product. During the first half of the 1900s, debate emerged regarding the preservation of Oslomarka – initially only parts of it and, with time, the entire area. The phenomenon of a park was a clear part of this debate. The term “park” provided a reference point with which to understand this recent phenomenon. Many people also saw Oslomarka as an historical extension of parks, both public and private. This coincided with extensive and more romantic notions of the forest as free land.

“This was a complex debate, evolving from several historical origins. One part of the dissertation is a study of the dynamic and tension between culture and nature in the development of Oslomarka. This cultural “fabrication” that took place was entirely decisive, so it is safe to describe Oslomarka as a type of park”, says Mytting.

One of the arguments in the debate was that Oslomarka should play a role in the lives of Oslo’s inhabitants. This was a modern administrative notion, establishing Oslomarka as a public recreation area for the weary urban citizens, just like the city’s parks. The landscape was made accessible for recreation and leisure pursuits. Oslomarka was shaped as an area of respite for the city.

Park roads and cabins

In 1936, Oslomarkas Friluftsråd – which changed its name to Oslo og Omland Friluftsråd in 1946 (Outdoor Council) – emerged on the scene, taking on a key role in this history. In the 1920s, the organisations realised that there were new discoveries to be made in Oslomarka; the forest area positively grew with an ever-increasing number of new explorations and new symbols and descriptions.

This trend took a new direction, however, as early as the 1930s, with the promotion of preservation of the area and the obstruction of destructive powers. It became more important to protect the landscape.

The Outdoor Council (Friluftsrådet) had two main tasks: To take measures to protect Oslomarka as a recreational area and to ensure the establishment of roads and ski trails linking the city to Oslomarka. The remains of these roads are still evident today, for example in Havnabakken and Damefallet.

Several cabins were also erected for hikers, but the history behind the excursion spots we know today is complex. Some date back to the early days while others are more recent.

Paths or gondolas?

Iver Mytting does not believe it is negative that this former area of wilderness has become a constructed landscape, with many features in common with parks.

“I provide nuanced descriptions of Oslomarka and other recreational areas as so-called free nature. The landscape is preserved and administered in very specific ways, and this shapes how we understand and use the area.”

But where to draw the line for the limits of positive adaptations? What about gondola cable cars, steel bridges over waterfalls, ski lifts?

“This is not something I covered in my dissertation, but people tend to easily forget how much infrastructure has already been established. The signposts and paths are examples of this, and some of these create problems, such as erosion. Such adaptations are often followed by methods to preserve nature.”

Iver Mytting believes that one lesson we can learn from the story he has told is that we should not take nature for granted. “Nature is not just something lying around and ready for us to use. Someone has taken measures to provide access, and we can be thankful that they had such foresight and had the public interest in mind. This kind of preservation work for the public interest is also something we should keep in mind today, for example when working on extensive developments along the coast or developing areas for cabins and holiday homes.”

A future on social media

Mytting believes that Oslomarka is extremely important for the city’s inhabitants, and that it shapes their self-image. It is just as important as the city itself, and Oslo’s citizens should be grateful for its administration, for the fact that the area has not been over-developed with satellite communities or extensive numbers of holiday homes.

So what about more recent communications, people’s descriptions of trips on Facebook, Instagram and other channels? Do they have the same function as the descriptions from the pre-war and interwar periods?

“I would say so, yes”, says Mytting.

“Nowadays, we have an even greater range of media on which to talk about and experience nature. People can enjoy outdoor pursuits from home. They can experience skiing, mountains and coastal landscapes in a much more lifelike way. But actual experiences in the outdoors are and will continue to grow in strength and will always be something that attracts people. Input from social media will only reinforce this.”