This article was produced and financed by NIBIO - Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research

Forest fires tell a 700 year old tale

Dead trees come alive and tell their story on how climate and human activities have shaped our boreal forests during the last 700 years – from the Black Death to present day.

The change of season encountered in northern boreal forests leaves a mark in the form of annual increment rings in the trees. Such annual tree rings from old wooden stumps show how old the tree was when it was felled, or damaged by forest fires. Forest fires can also scar the annual tree rings and leave marks that tell scientists whether the fire burnt early or late in the growth season.

By collecting and analyzing old tree stumps scientists can use the history of the forest trees to reconstruct events several hundred years back in time.

In a recent article in the journal Ecological Monographs scientists at NIBIO, the Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research, have done just that. Together with former PhD-student Ylva-Li Blanck at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences, researchers Jørund Rolstad and Ken Olaf Storaunet collected and analyzed tree rings from fire-damaged pine tree stumps in a boreal forest nature reserve in Southern Norway.

The old wooden stumps tell a 700-year long history of man's use of a northern boreal forest – about climate and forest fires – from the end of the Black Death to present day.

Tree rings

"The tree rings show how high summer temperatures and human activity – in the form of slash-and-burn cultivation and rangeland burning – have affected the number and extent of forest fires in the forest over the past 700 years," explains NIBIO Senior Research Scientist Ken Olaf Storaunet, one of the authors behind the study.

In a research project financed by the Norwegian Research Council, the forest researchers collected 459 wooden samples from old, burned pine trees and stumps from a 74 km2 area of Trillemarka-Rollagsfjell nature reserve in Southern Norway.

Storaunet explains how the collected samples were cross-dated using dendrochronology, a method where tree rings in wooden samples are compared with a known chronosequence from many other collected and dated year ring series. This way scientists can determine the date and location of forest fires with great accuracy. Based on where in the year ring the damage occurred, forest researchers such as Ken Olaf Storaunet can also tell at what time during the growth season the tree burned.

The research area, Trillemarka-Rollagsfjell nature reserve, was established in 2002. Although the nature reserve appears relatively unexploited today, humans have left their marks in the form of old tracks, settlements, historical records, and, not least, in fire scars on stumps from burnt trees.

Fires cause dramatic changes

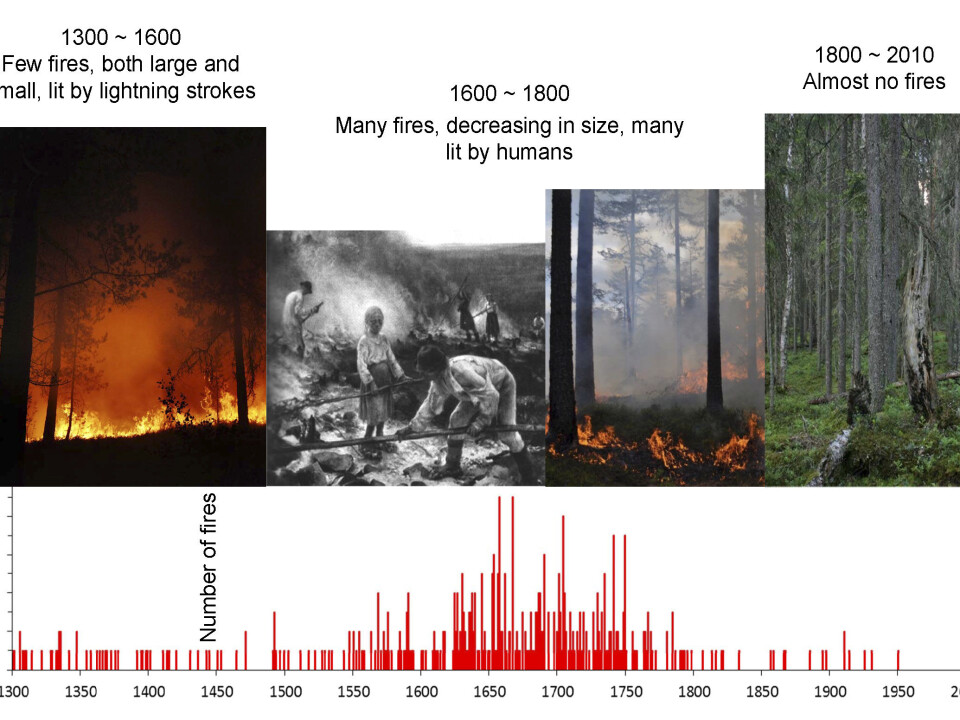

The collected wooden samples revealed 745 fire scars from 254 different forest fires. The oldest forest fires preceded the Black Death (1350 AD). The results from the analysis of the wooden stumps revealed a pattern where climate affected the number of forest fires in the period up to 1625. After 1625 there were many human-set fires. From 1800 to present the frequency of forest fires was reduced due to stricter rules against burning forests, and due to a higher timber value.

Lightning was the main culprit behind the forest fires from the time of the Black Death towards 1625, and mainly in years with warm and dry summers. The forest fires took place at the end of the growth season, in July-August – the months with the highest number of lightning storms. The forest area affected by forest fires was also greatly increased in years with higher summer temperatures.

During 1600s and 1700s the number of forest fires increased dramatically. On average, the period between each forest fires was reduced from 73 to 37 years. Many of the fire scars where also observed early in the trees’ growth season, something that did not happen in the years preceding 1600. The increased number of early season fires coincided in time with humans starting to use fire, probably to increase conditions for grazing animals.

Not happened in thousands of years

"Ecologically, the period from 1625 and onwards to today is probably unique, and something that perhaps has not happened in thousands of years," Senior Research Scientist Ken Olaf Storaunet explains. Storaunet is one of the authors behind the fire history article.

Rangeland burning and slash-and-burn cultivation lead to a strong increase in the number of forest fires. With the increased timber prices comes a law against burning on forest land, something which drastically reduces the number of forest fires. After 1800, fires almost ceased to exist in the studied research area.

The dual role of forest fires

Forest fires can be catastrophic and damaging for both house owners and the forest industry. In Canada each year, on average, 8600 forest fires burn 25 000 km2.

At the same time forest fires play an important and integrated part of our northern boreal forests.

"Yes, forest fires play an important role in the turn-over of nutrients and global carbon dynamics," Storaunet explains.

Forest fires create a mosaic of burnt and unburnt areas, something that affects the species composition and the age distribution of the forest.

"Manly people believe that natural forests consist of a continuous expanse of old trees. This is not correct. Many of today’s forest reserves have perhaps never been as unnatural as they are today," Storaunet points out.

Forest fires are important for biodiversity

A forest fire opens up the tree canopy, lets light in, releases nutrients to the understory, and strengthens the regrowth. Charcoal from the burnt wood changes soil structure, and charred tree trunks become habitats (living areas) of great importance for the biological diversity of the forest – both above and below ground. Many rare species, especially fungi and insects, depend on the variation forest fires create.

"Our historical study in Trillemarka-Rollagsfjell nature reserve shows that fire has been a natural, and very dynamic, part of the forest ecosystem throughout history. And this ecosystem is affected by climate, vegetation and not least the way humans use forest land," Storaunet concludes.