THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY NUPI - Norwegian Institute of International Affairs - read more

Controversial calories: How do we measure hunger?

Today, it seems obvious that food, and consequently hunger, is measured in calories. But how did this unit of measurement emerge, and why is it more controversial than one might expect?

For most of us, the calorie is a familiar concept – something we count on food labels or burn off at the gym.

In a new academic article, senior researcher Thor Olav Iversen explores how the calorie evolved from being a tool for controlling workers to a global indicator of hunger and development.

However, this development has not been neutral. The way hunger is measured has been shaped by political interests and institutional needs.

The origins of the calorie

The calorie was not solely developed to measure hunger. It was meant to improve labour efficiency.

In the late 19th century, during the industrial revolution, factory owners wanted to calculate the minimum amount of food a worker needed to remain productive.

“Originally, the calorie measurement was inspired by combustion engines. The goal was to quantify how much energy humans expended in order to calculate the precise minimum food requirements – and, thus, the lowest possible wages,” says Iversen.

Over time, the calorie became a standardised tool that allowed for comparisons of nutrition across countries and regions.

“The League of Nations first began using the calorie as a standard for food requirements, and after the second world war, it became a cornerstone of the UN’s work on food security,” says Iversen.

Since 1946, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has used calorie data to estimate global hunger. While this has made hunger and food security visible across borders, it has also simplified a highly complex issue: how people relate to food.

One billion hungry?

Despite the long tradition of using calorie intake to measure hunger, Iversen’s research shows that FAO’s methods have changed significantly over time – with major political consequences.

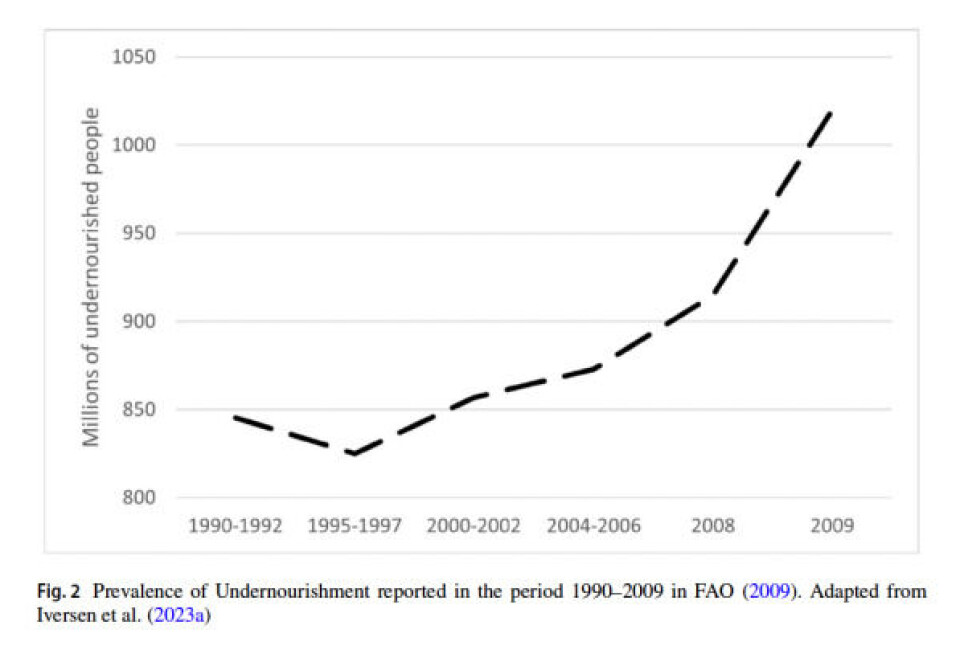

“Until 2010, FAO’s statistics indicated that global undernourishment was increasing. However, at the same time, the World Bank reported that global poverty was decreasing. How could hunger rise while poverty was declining? This created a methodological and political conflict,” he explains.

Undernourishment and poverty are usually seen as connected. The UN faced particular criticism for reporting that more than one billion people in the world were undernourished. FAO responded by revising its methodology.

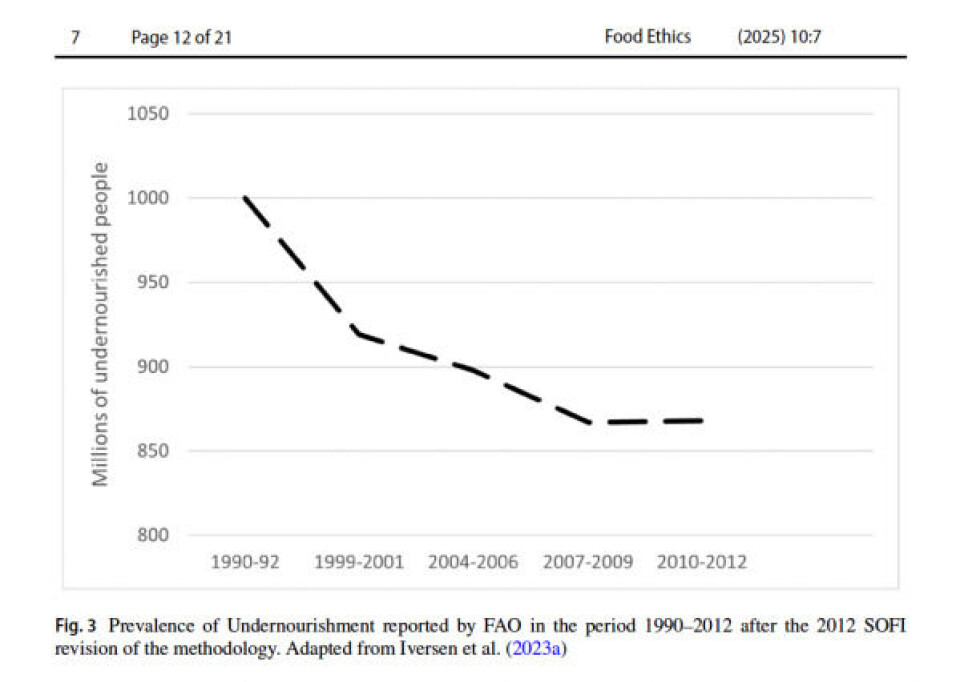

“In 2012, FAO adjusted its model, and the trend completely reversed. Suddenly, the numbers showed that global hunger had actually been declining since the 1990s,” explains Iversen.

This shift happened just as the UN’s Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) neared their 2015 deadline. The new numbers gave the impression that the global fight against hunger had been a success.

China’s impact

Another drastic change came in 2019, when FAO gained access to China’s hunger statistics for the first time in 20 years. Until then, its estimates for China were based on outdated data from the 1990s.

“China only gave the UN access to new data after the country succeeded in having a Chinese leader of the FAO elected for the first time in 2019. This led to the estimated proportion of undernourished people in China dropping from 10 per cent to approximately 0 per cent,” says Iversen.

Given China’s massive population, this caused a significant drop in global hunger numbers.

This sudden revision highlights the instability of hunger statistics. The numbers depend not only on how many people are actually hungry, but also on the data used, how it is calculated – and who has the power to decide what counts and when.

From numbers to reality

Today, the UN uses two main indicators to track hunger as part of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Prevalence of Undernourishment (PoU) and Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES).

PoU, which was introduced by the FAO in the 1960s, is a model-based estimate derived from the available calorie supply in a country. FIES, on the other hand, is a newer measure based on household surveys where individuals report their own experiences with food security.

“The PoU indicator is designed for global analysis but provides little insight into local or individual experiences of hunger,” says Iversen.

The countries with the lowest food security often have the least survey data available.

“This is concerning seeing as those most in need of assistance and support are often the least represented in the statistics,” he says.

Iversen argues that measuring hunger exclusively through calories reinforces a production-focused view of food – one that prioritises how much food is produced, rather than how it is distributed or whether people receive the types of food necessary for a healthy life.

The future of hunger statistics

Simultaneously, the SDGs are under pressure. At a recent session of the UN General Assembly, the US representative stated that the SDGs no longer align with American national interests.

Hunger statistics are also tied to conflict. In Gaza, famine has been used as a weapon of war.

“This demonstrates the importance of viewing hunger not just as a statistic, but as a politically created reality,” argues Iversen.

His research highlights the challenges of using the calorie as a measurement tool, showing that it is shaped by norms, values, and political interests.

“Hunger measurement is never neutral. If we truly want to combat hunger, we must ask critical questions about how we count the hungry,” he says.

Reference:

Iversen, T.O. Care, Control and Calories: A Genealogy of Measuring International Undernutrition, Food Ethics, vol. 10, 2025. DOI: 10.1007/s41055-025-00164-2

This content is paid for and presented by NUPI

This content is created by NUPI's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The Noprwegian Institute of International Affairs is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

More content from NUPI:

-

The war in Ukraine: "France and the UK clearly stand out"

-

How Iran’s regime exploits emotions to crush protests

-

Improving the impact of the UN Peacebuilding Commission

-

How Norway and the EU can collaborate in the minerals and battery sector

-

Nigerian authorities plan to close refugee camps housing a million people

-

How Central Asia can help the global energy transition