An article from KILDEN Information and News About Gender Research in Norway

Burning porn in Norway, fighting rape in France

Why did Simone de Beauvoir fight rape in France while Unni Rustad simultaneously became famous in Norway by burning porn magazines?

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Factors such as national differences and personal experiences may help explain why the struggle against sexual violence manifested itself so differently in the two countries.

“The publications produced by French feminists in the 1970s are pervaded with descriptions of rape,” says Trine Rogg Korsvik.

“They give the impression that women walking the streets of France were fair game. That women were saying no to men who insisted on having sex was regarded as part of an erotic game in France."

The sexologist Michel Meignant claimed that women subconsciously desire to be raped. Moreover, French research shows that the French society in general was remarkably tolerant towards rape.

Nobody in Norway thought that rape was ok. This made it easier to embark on the struggle against pornography, claims Korsvik.

"The French feminists were also against pornography, but they had to use their energy on convincing people that rape was wrong," she says.

Makes women’s history visible

In her PhD project Korsvik examines how the feminist movement’s fight against sexual violence manifested itself in the two countries in the period in question.

The political movements have been studied through careful readings of the feminist movement’s magazines, newspapers from the period, some radio- and TV recordings, and interviews with some of the Norwegian activists.

While the fight against rape in France has played a central part in the historical accounts of the French feminist movement, the fight against porn in Norway has been paid relatively little scholarly attention.

Moreover, as opposed to the struggle for abortion – which is to be regarded as a success – the feminist movement did not achieve what they wanted with the legal acts they had fought through concerning pornography and rape in the respective countries.

Rape is still a widespread problem and the porn industry is alive and well.

Porn captures public sphere

The Norwegian feminist movement also fought rape, but that was never the big issue. Where French women related horrible stories about rape, Norwegian women talked about dismissed rape cases.

On the other hand, porn came to be regarded as a big problem. In the mid-70s, three new porn magazines were launched: Nye Alle Menn (“New All Men”), Express and Leif Hagen’s Aktuell Rapport (“Current Report”).

“There was strong competition between the publishers and intense marketing in the public sphere. People were not used to this, and many were very provoked,"says Korsvik.

In the beginning, the women activists claimed that the problem with pornography was that women felt inadequate compared to the ideals as shown in the porn magazines.

Once they started to take action against porn they became aware of the porn models’ terrible working conditions, and thus started to connect pornography to prostitution.

French revolutionaries, Norwegian pragmatics

One of the major differences between the two countries’ feminist movements is that the Norwegian movement was more pragmatically oriented, claims Korsvik.

“The two countries had a very different political culture. Consequently, the two feminist movements operated differently. The French Mouvement de libération des femmes, MLF, had an uncompromising and revolutionary style. For them it was all or nothing."

"The Norwegian feminist movement, on the other hand, was down to earth and pragmatic. They were prepared to cooperate with others even though they did not necessarily agree on all things,” says Korsvik.

For instance, the Norwegian feminist movement formed an alliance with Christian women in the fight against porn. But, according to Korsvik, the Christian women in Norway did not manage to coup the anti-porn movement in the 80s, as they did in the US.

“The banners were never puritan. There were lesbian slogans and banners demanding sexual education. I find it fascinating that the conservative women and Christian activists were so open to radical feminist slogans," explains Korsvik.

"They stood side by side with the feminists and distributed flyers saying ‘no to the porn industry’s exploitation of lesbian women’.”

Korsvik’s studies also suggest that the Norwegian feminist movement was larger than the French, both in terms of number and breadth. Yet France legalised abortion as early as in 1975, three years before Norway.

Elite activists

There were also major ideological differences within the movements.

Both in Norway and in France there was a divide between those who gave precedence to the class struggle and those who cared mostly about women’s common experiences and the fight against the patriarchy.

However, many of the conflicts in France revolved around a third, distinctively French movement: The group Psychoanalyse et politique had a psychoanalytic perspective on their activism and believed that women, by virtue of their uterus, were fundamentally different from men.

The group was led by the intellectual celebrity Antoinette Fouque, was financed by a billionaire sympathiser and had its own publishing company and journal.

“Fouque fronted the business, she took mistresses and created her own entourage. This is fairly typical for French political and intellectual culture,” says Korsvik.

Fouque was, however, challenged by other intellectuals such as Beauvoir and Sartre. They emphasised gender as a social construct and they played major parts in the struggle against rape.

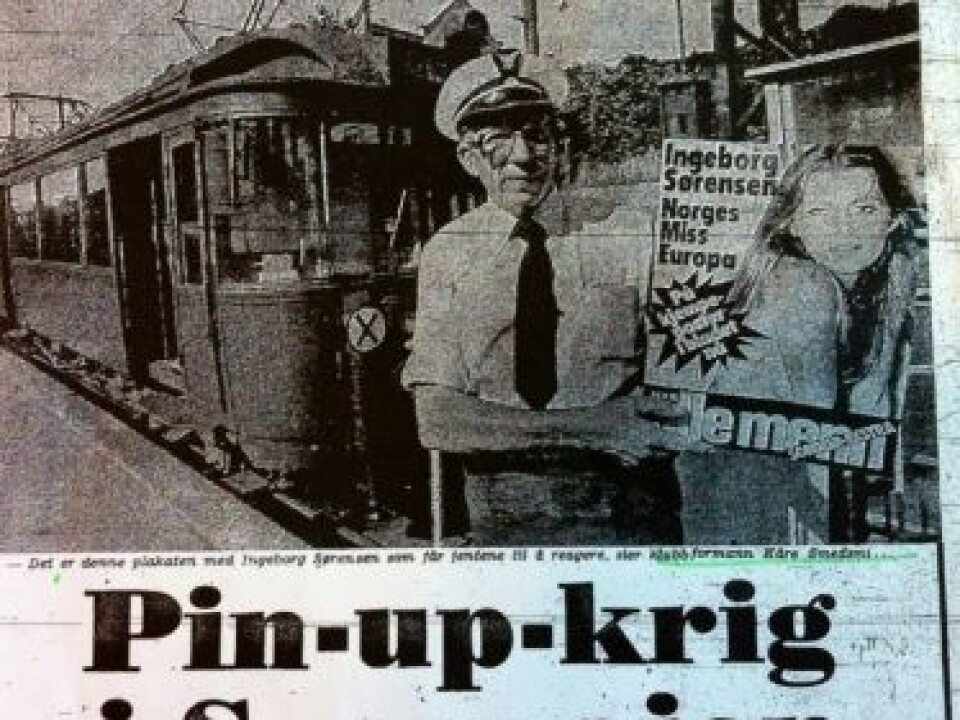

Porn on the tram

The fact that pornography and rape became the main issues on the agenda was a consequence of two particular incidents.

During the summer of 1977, tram conductors in Oslo protested against advertisements for porn magazines on the trams.

A national newspaper wrote “The feminists are raging: Pin-up war on the tramways”. Two summer temporaries were suspended after having removed advertisement posters.

“Various women’s associations formed a solidarity demonstration for the two temporaries. And as they started to study the contents of the porn magazines, they found everything from child porn to animal porn and abuse. This upset them”, says Korsvik.

The incident which became the symbolic main issue in France happened in 1974, when two lesbian women from Belgium were raped on a camping site just outside Marseille. The two women took the unusual step to report the incident to the authorities.

“This connection to concrete figures and incidents was important. Only then, these problems became major issues that reached the public sphere. Furthermore, these women – both the Belgian tourists and Liv and Ranveig – were actively taking part in their own cases.”

Gisèle Halimi, the two Belgian women’s lawyer, was a French celebrity.

In Norway, Unni Rustad became the public face in the fight against porn. She travelled around the country giving lectures about pornography, she burnt porn magazines, participated in debates on television and were portrayed in the Saturday newspapers.

Porn struggle sells

The Norwegian struggle against porn became a media sensation.

“The struggle against porn in France received hardly any media attention at all, although women activists attacked porn shops with iron rods and broke windows,” says Korsvik.

One explanation may be that France is so much bigger than Norway; there are more people and more things going on, which makes the fight for the media’s attention much harder.

More importantly perhaps, is the fact that France did not have tabloid newspapers such as Norway.

“The fight against porn was perfect material for the tabloids,” Korsvik comments.

However, the French papers wrote very detailed about rape cases, especially before trials. In Norway, a rape was hardly covered by the newspapers at all unless it was in connection to a murder trial.

A real porn pig

Another factor which made the fight against porn so visible, both for the tabloids and the women activists was the porn dealer Leif Hagen.

“The effect of having such a prominent enemy as Leif Hagen should not be underestimated. Following an incident where women activists protested by burning porn magazines in public in 1977, he threatened them with gangsters through the media," says Korsvik.

"He named several well-known feminists and more or less encouraged people to rape them. He became the incarnation of a porn pig, a rich boy who appeared on photographs with a big white fur coat and naked women in the background. And he never tried to conceal that he did it for the money.”

The triumph’s defeat

In France the fight against rape won territory. The newspapers wrote about traumas which had previously been ridiculed, and the penalties imposed on rapists became harder and harder.

Nevertheless, the French activists regarded their struggle as a defeat. They were hassled by the political left side who argued that their campaigns contributed to suppression and legitimised and strengthened bourgeoisie institutions.

Not only was the image of the enemy in the French rape trials unclear, also, due to the extremely harsh penalties imposed by the French judiciary, many people felt sorry for the convicted rapists.

“Nobody felt sorry for Leif Hagen when he was deprived of the right to conduct his business. But when an unemployed immigrant was sentenced to 20 years in prison for rape, it was not regarded as a victory. It was much easier to accept such penalties if the convicts were directors in leading positions,” says Korsvik.

Moreover, getting acceptance for their struggle with the authorities was not regarded as a victory by the French feminist movement. It was rather the opposite. According to Korsvik, the French revolutionaries regarded recognition from the state, the institutions and the established political parties as a sign of failure.

It implied that the struggle had lost its radicalism, which was seen as a defeat.

The Norwegian activists, on the other hand, regarded it as a breakthrough when they managed to convince the politicians and the police to take their side. It was a triumph for them when the authorities decided to pounce on hard-core porn.

Although the results of the struggles in Norway may not be seen as a great success today, Korsvik is of the opinion that the feminists in the 70s and 80s achieved much.

“It altered the way people talk about porn. The same arguments against pornography are still in use, and even members of the Christian Democrats (KrF) are using feminist arguments when they are discussing pornography.”

Reference

Trine Rogg Korsvik: ‘Pornography is the theory and rape the practice’: Women’s struggle against rape and pornography in France and Norway ca 1970-1985” (Norwegian title: “Pornografi er teori, voldtekt er praksis”: Kvinnekamp mot voldtekt og pornografi i Frankrike og Norge ca. 1970-1985").

Translated by: Cathinka Dahl Hambro