This article was produced and financed by The Norwegian School of Sport Sciences

Why are they playing with death?

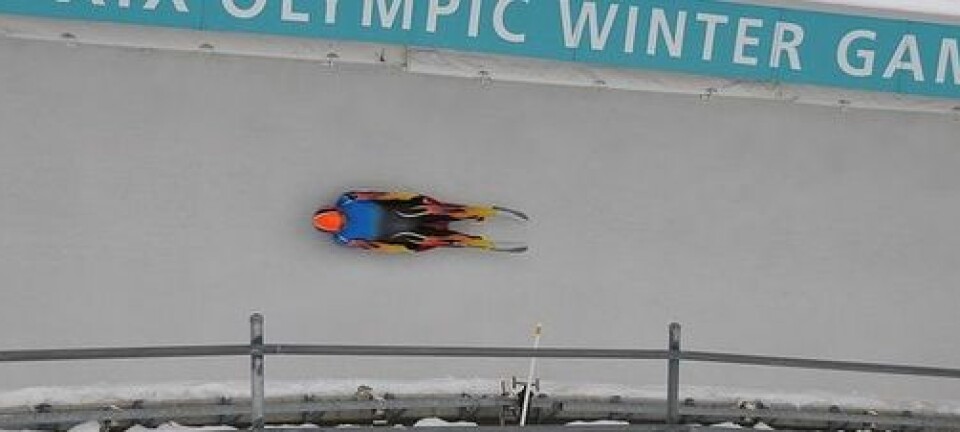

Do they throw themselves off cliffs to achieve status in the base jumper community or to simply feel good? Researchers disagree.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Performing dangerous acts results in increased status and more recognition within the community, says Tommy Langseth.

"No, they are driven by their perceived coping," says Audun Hetland.

Langseth and Hetland are both PhD-candidates in extreme sports. They both explore what motivates base jumpers. They are both from Rogaland in the west of Norway, and they met each other collecting data in 2008. But the similarities stop there.

Seeking risks

Tommy Langseth is a doctoral research fellow at the Norwegian School of Sports Sciences and is completing a PhD in sports sociology. He has studied how some subcultures, like base jumpers or surfers, develop their set of values.

His dissertation is based on interviews with people doing different kinds of extreme sports.

"Extreme sporters seek risks. By taking risks, they achieve higher status. Recognition from your peers is the most important driving force for doing extreme sports. The most daring jumpers receive the most credibility and recognition," he says.

Audun Hetland is completing a doctoral degree in psychology at the University of Tromsø. He won the Researcher Grand Prix in 2011 for his lecture on the minds of extreme sporters.

He has measured the level of satisfaction and dissatisfaction in the minds of base jumpers prior to, during and after the jump.

"They are not driven by risk taking, but by the satisfaction they get from mastering very difficult tasks," Hetland says.

"Base jumpers are always trying to minimise the risks. They practice and invest in better equipment to make the jumps more safe. A person who takes too many risks, like not using safety equipment, would be regarded as an idiot by most of the extreme sporters."

Recognition loses value with experience

Hetland believes status and recognition become less important as the extreme sporters become older and more experienced.

"One example is the climbing community in Romsdalen, in the north of Norway. Many complete extremely difficult climbs without telling others. It's all about you enjoying the activity, not impressing your community."

Langseth also knows of Romsdal climbers, who keep quiet about their most dangerous climbs.

"Climbers know that you receive the most recognition from doing difficult climbs without disclosing it to anyone. But somehow, the right people in the climbing community are always informed about the latest accomplishments," he says.

In his dissertation, Langseth discusses how the extreme sport communities develop their own set of values. The tasks with most status among key people in the community, are the ones other members are most happy to master.

"This is perceived as an internal motivation. But, the motivation is established by the community, not the individual," he claims.

Hetland disagrees.

"As a person gains more experience, status becomes less important. This is something he has achieved already. You can draw parallels to other sports, like running. Why does someone chose to compete in the New York Marathon every year? It is expensive, time consuming and very painful."

"And, regardless of how fast you run, you will most likely be left behind by an African runner. You will not achieve higher status, but the feeling of making it to the finish line, perhaps a bit faster than last year, is amazing," he says.

A central bank for symbolic capital

New media platforms have emerged as extreme sports have become more popular. Hetland has for many years documented expeditions and trips. A number of his adventures has become TV-documentaries.

"The main goal is not to show off what you have accomplished. It is about reliving the satisfaction you get, for example from base jumping. Also, it is rewarding to share this experience," he says.

"That is nonsense," replies Langseth.

"If you ask people directly, they might answer something like that, but that does not make it true. I refer to YouTube as a central bank for symbolic capital. Conventional capital can be amassed and saved. It is only recently, that the capital which is valued the most in extreme sports communities, namely the experiences and achievements, can be saved," says Langseth.

He claims that no one would do extreme sports if there were no spectators.

"Every healthy person relates to others through social structures. A few individuals or some select subcultures define what is cool. Other people develop feelings tied to this."

"These values become intrinsic, and we are no longer aware of the fact that they are shaped by a value system. You do not make a conscious decision to make it to the top of the chain, but everyone strive to cope. We seek recognition."

Disagreement or nuances

Hetland and Langseth do not disagree on how motivation is perceived by extreme sporters, but they disagree on what creates the motivation.

"Psychology is based on the individual, while sociology examines social networks. Our findings are not polar opposites but can serve to complement each other," says Langseth.

Hetland is happy to see that this research field is being approached differently:

"Extreme sports is not a new trend, but a complex and intricate field. I focus on some of its aspects from my academic viewpoint and Langseth examine others," he says.

Tommy Langseth defended his dissertation at the Norwegian School of Sports Sciences November 30th 2012. For Audun Hetland, a couple of years remain of his doctoral studies.

---------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Thomas Fagerlid