This article is produced and financed by Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences - read more

Sustainable tourism: Can your oyster safari make a difference for our planet?

A new innovative way of looking at sustainable tourism development shows how leisure and caring for our planet may be one and the same – and how even the smallest acts add up to global impact.

The quantitative fallacy, also known as The McNamara Fallacy, is a logical fallacy that holds that only things that can be measured quantitatively have proven value for decision-making. This may lead people to misjudge or disregard complex situations – attempting to reduce them into something straightforward and simple.

This has been the case for the concept of “sustainability” – It has been viewed as a goal-oriented process, with a starting and a finishing line. While this may be an enticing idea, reality proves more complex.

“In sustainable development, it is usually assumed that one is facing a linear endeavour, and most often the focus is on the outcome – and is overtly financially oriented – rather than adding a focus on the process and the values involved,” says Eva Duedahl, a PhD candidate at INN University.

Together with Arvind Singhal of the University of Texas at El Paso and INN University she has looked into some of the complexities of sustainable development. The two have looked for and found interesting cases that can illustrate how small acts can generate cumulative effects.

“Sustainable development has to be looked at as a transition, a process of constantly becoming, rather than a goal with a distinct start and finish,” says Duedahl. “We also wanted to look into things with unpredictable and maybe even surprising outcomes. The whole point of this way of considering innovation is exploring how novel ideas may lead to outcomes that couldn’t have been fully predicted and planned in advance.”

Harvesting invasive oysters

Duedahl and Singhal have studied two cases of sustainable tourism development.

The first case, called “Picking our oysters” follows the oyster safaris in the UNESCO World Heritage Wadden Sea National Park, Denmark. The national park has opted for a creative approach in which it has established a programme allowing local stewards to host oyster safaris. In these safaris international and national tourists – under guidance and tutelage – harvest invasive Pacific oysters.

In the 1980’s the Japanese Pacific oyster was released on a German barrier island in the Wadden Sea as part of a managed agricultural experiment. Overtime the oysters made it to the Danish side and have pushed shellfish and blue mussels on which many birds feed, out of the birds’ reach. The oysters themselves cannot substitute these sources of nutrition as they are too tricky for the birds to crack open.

The oyster safaris allow tourists to pick oysters (under instruction), as well as learn about their preparation, storage and consumption. While the growth in the oyster population is more rapid than what tourists can harvest, their efforts are still helpful in mitigating the problem, according to the national park.

Taking pictures of whale sharks

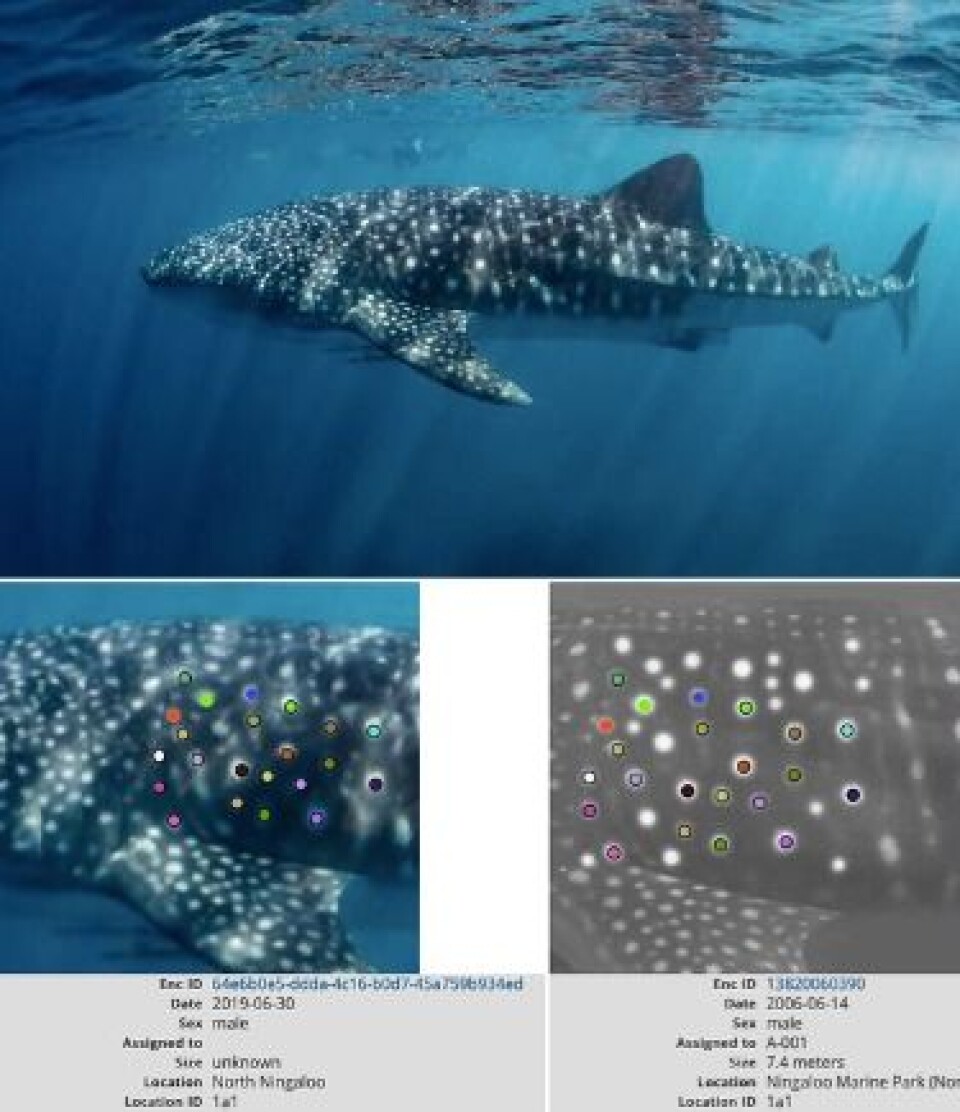

The second case, “Swimming with our whales,” revolves around a sustainable tourism initiative born at Ningaloo Reef off northwest Australia. There, tourists have the unique opportunity to dive and swim alongside whale sharks. They also get to photograph them.

Brad Norman (of Ecocean, an Australian NGO) who leads these expeditions had been trying to catalogue shark photos to keep track of the endangered animal. Struggling to catalogue the photos by looks alone, Norman met Zaven Arzoumanian, a NASA astrophysicist, who used an algorithm to identify star patterns in the night sky. As it turned out, the same algorithm could be used to identify individual sharks using their unique spot markings.

Nowadays, tourists around the world get to photograph whale sharks and upload the images to a database where the advanced 3D software helps catalogue them. Each individual photo may seem like a drop in the ocean, but the database makes a vital contribution to the conservation efforts of the whale shark.

“These two cases feature things that are not immediately obvious,” says Duedahl. “It’s about opportunity, emergence and surprise. Through focusing on the journey – and on values – we can reach unexpected outcomes.”

A deeper reverence for nature

Sustainable tourism development isn’t a gimmick or an attempt to guilt people into undesired free labour. The idea is that it benefits the environment and also the participants. Yes, the activities are enjoyable in and of themselves, but it is much more than just that. As Duedahl and Singhal note, tourism has traditionally been an activity that has tended to exploit nature, rather than have no effect on it or be beneficial to it.

Sustainable tourism development is also not a lip-service to the notion of being “one with nature” as a shallow concept, according to the researhcers.

In the cases studied humans interacting with others and with nature through local tourism not only sparked cascading beneficial effects of growing communities of nature-care, they’ve also gained a deeper reverence for nature through their first-hand interaction with it.

From waddling on the beach, to learning about oysters, to finding the perfect ones to consumption, intimate engagement is created.

By swimming alongside the majestic whale shark tourists experience an irreplaceable interaction while doing their part for natural preservation.

The uniqueness of both cases is that you can’t experience them anywhere but their natural environment, while becoming part of a caring community of nature sustaining ambassadors.

Tourist and research assistant

The cynics among us may still tilt their heads and wonder whether the cumulative effect is significant. Sure, we know that when we all recycle plastic bottles less of them end up in the ocean.

But can a lone tourist with a camera really make an effort outside of a state-regulated effort?

According to Norman, the answer is “absolutely.” With the limited time and number of scientists dedicated to field work and the vast area in need of coverage, he views each tourist with a camera as a research assistant. According to him, their input is a major part of the global whale shark monitoring system. On a grand scale, efforts like this can mean the difference between extinction and preservation for a species.

Small actions do matter

Looking into the specific cases has been illuminating. The researchers hope this sparks both an interest in sustainable tourism development and more research on the topic.

“We want to spark the idea that we can all contribute to sustainable development and that small actions do matter.” Says Duedahl.

“We want to promote the value of dwelling in the here and now, and seizing opportunities, rather than overly prescribing processes and planning outcomes in advance. This is what innovative tourism practices mean here.”

The researchers believe that if we do that, we may begin unfolding the complexities and values of tourism, and nurture even more latent opportunities. They caution that an important thing to remember is that values can lead to choices that harm, and they can lead to choices that benefit.

“It’s about living with more awareness, more responsibly. It’s about knowing that a personal choice to care for our oceans and nature in general does matter”, says Duedahl.

Part of something bigger

She hopes the study also can serve as a thank you to those who currently engage in nature sustaining activities. Distant tourism practitioners have sent thank you messages to the researchers, for showing the importance of such activities, and for demonstrating that all these efforts are a part of something bigger.

With the corona-crisis still not resolved on a global scale, while long-distance travel is not an option, small acts of care can be implemented during local nature exploration or domestic travel and still have a global effect.

Perhaps, a new way of vacationing will slowly become the norm, and a growing number of people will incorporate sustainable efforts into their leisure time.

Would you consider a small positive gesture in your next vacation?

Reference: