This article is produced and financed by NIVA - Norwegian Institute for Water Research - read more

Sea urchin grazing of kelp may worsen negative effects of oil spill in the Arctic

Heavy sea urchin grazing of kelp forests along the coast of Northern Norway has worried fishermen, researchers and others for decades. Together with the increased oil activity in Arctic waters, sea urchin grazing poses an additional hazard: will an oil spill in an area already overgrazed by sea urchins mean the end of the intertidal communities as we know them?

“The oil activity in Northern Norway has increased the last years. Land terminals and new traffic routes have been established along the coast, leading to an increased risk for accidents and oil spills. This demands for action plans that are customized for the Arctic coast and ecosystem,” says marine biologist Trine Bekkby, senior researcher at the Norwegian Institute for Water Research (NIVA).

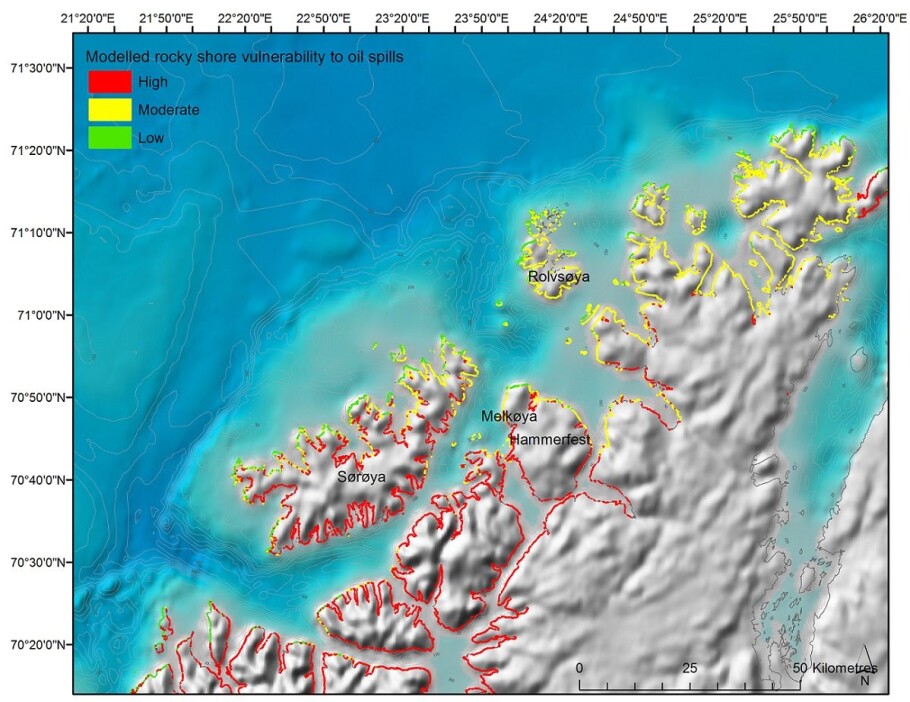

Together with research colleagues from NIVA, the Institute for Marine Research, Akvaplan-niva and the Norwegian Polar Institute, Bekkby has studied the combined effect of oil spill and sea urchin grazing on the coastal communities off Hammerfest in Finnmark, Arctic Norway.

Wave sheltered kelp communities are the most vulnerable

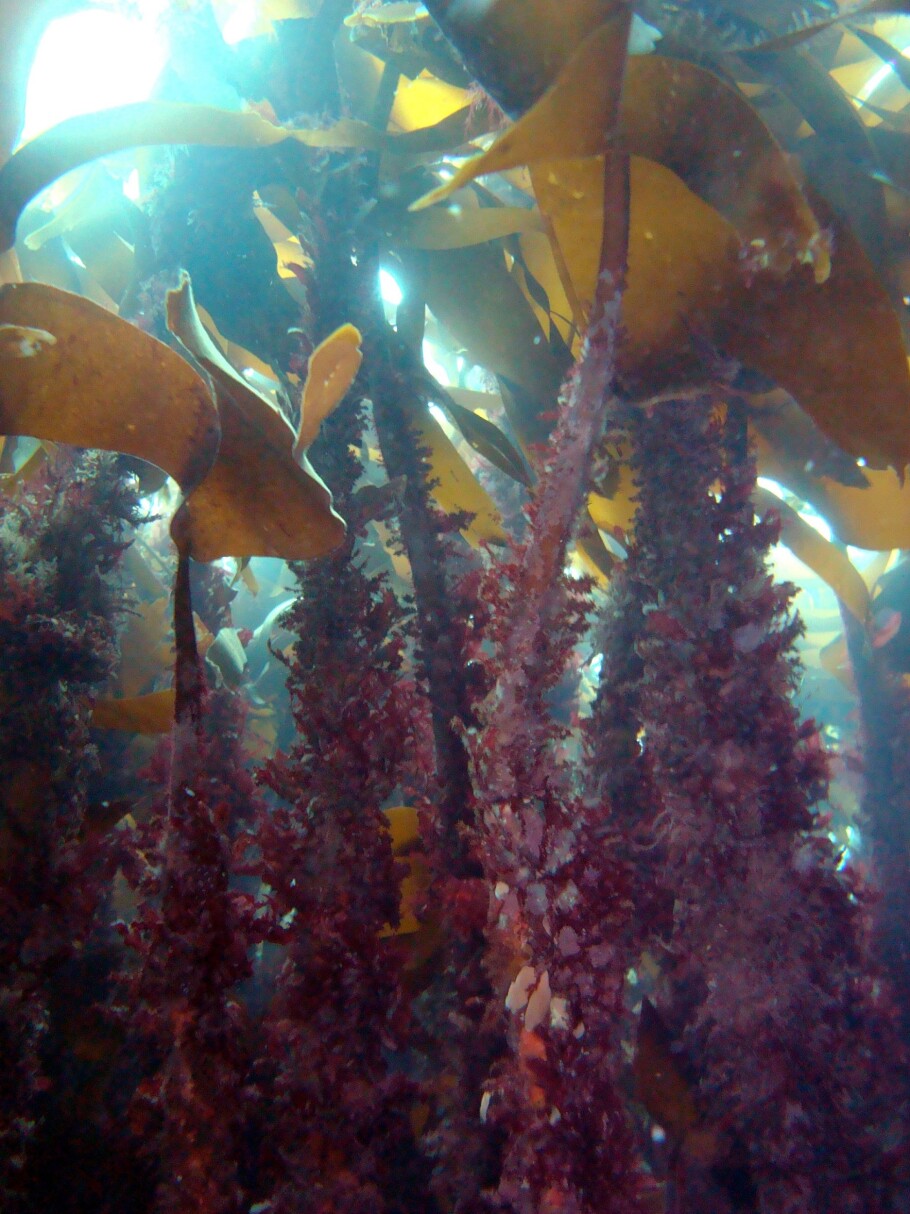

Using underwater camera and GPS, the researchers registered kelp distribution at more than 450 different sites around Hammerfest in Northern (Arctic) Norway. They also dived and snorkelled in the kelp forests, in sea urchin grazed areas and in the intertidal zone, collecting samples of the animal life living there. The researchers also deployed artificial substrates, or fauna traps, to investigate how fast small animals, such as crustaceans, polychaetes and molluscs, are able to colonize new habitats.

“In the last 40 years, there has been a shift from rich kelp forests to naked barren grounds dominated by sea urchins. We only find intact kelp forests in the most wave exposed areas,” says Bekkby.

Sea urchins are not abundant in wave exposed areas but they thrive in sheltered waters. Sheltered waters are also where it would take the longest for the oil to be washed away should there be an oil spill.

“Oil is especially harmful for crustaceans, polychaetes and molluscs. Their living grounds are kelp forests and seaweed bed, and those who live in the intertidal zone are particularly exposed to oil spills. If the animal life in one area is destroyed due to an oil spill and grazing from urchins have removed the nearby kelp and seaweed habitats, there is no place where the animals can recolonize from, and they will not be able to re-establish,” the NIVA researcher explains.

Crustaceans, polychaetes and molluscs appeared to be numerous in healthy kelp forests and in the intertidal zone. If these animals disappear, an important link in the energy transfer of the food web would be lost.

Hence, coastal areas without nearby kelp forests are especially vulnerable to oil spills and were classified as «highly vulnerable» by the researchers in their evaluation of the coast. More than 50 % of the coastal areas belonged to this category, according to the researcher’s models. Only 10 % of the areas belonged to the category «low vulnerability», and those were exclusively exposed coastal areas.

Tailormade actions at the right time

At the most intensive, Bekkby and her colleagues found more than 20 sea urchins per square meter. However, even in these areas, they found small patches of remaining kelp; small oases of kelp and associated wildlife with the potential to spread and re-establish forests when the day arrives that the conditions are suitable, and the sea urchins have disappeared.

“Our mapping of kelp abundance and vulnerability towards oil spills should be the basis for the clean-up strategy in the case of an oil spill,” Bekkby says.

Hence, a potential oil spill in sea urchin dominated areas does not necessarily mean the end of the intertidal communities. However, to prevent this to happen, managers should be prepared with customized action plans and apply them at the right places.

This project was a cooperation between researchers from NIVA, the Institute for Marine Research, Akvaplan-niva and Norwegian Polar Institute, and was a part of the project Arctic Seas Biodiversity (ASBD), receiving funding from Eni Norge (contract P289).