This article was produced and financed by Norwegian centre for E-health research - read more

Mobile health tools should be studied using new methods

By analysing how patients use mobile health technology it is possible to understand the health affects of the apps and those who they affect. Researchers believe that traditional research methods are not suitable.

Patients with diabetes type 2, who register their blood sugar, diet and physical activity on mobile phones, have the possibility to reduce their long-term blood sugar levels.

This is one of several results of a study conducted by researchers at the Norwegian Centre for E-health Research and Oslo Metropolitan University.

One study participant says that the collection of data over a prolonged period of time allows one to see how their blood sugar behaves.

“I have the possibility to correct my blood sugar if it is too high or low. In this way, I can reach my goal of having the lowest possible blood sugar levels. Not only do I record how my body is reacting, but I also receive good tips and feedback while collecting data without noticing it. I’m very happy about this,” he says.

101 diabetes patients

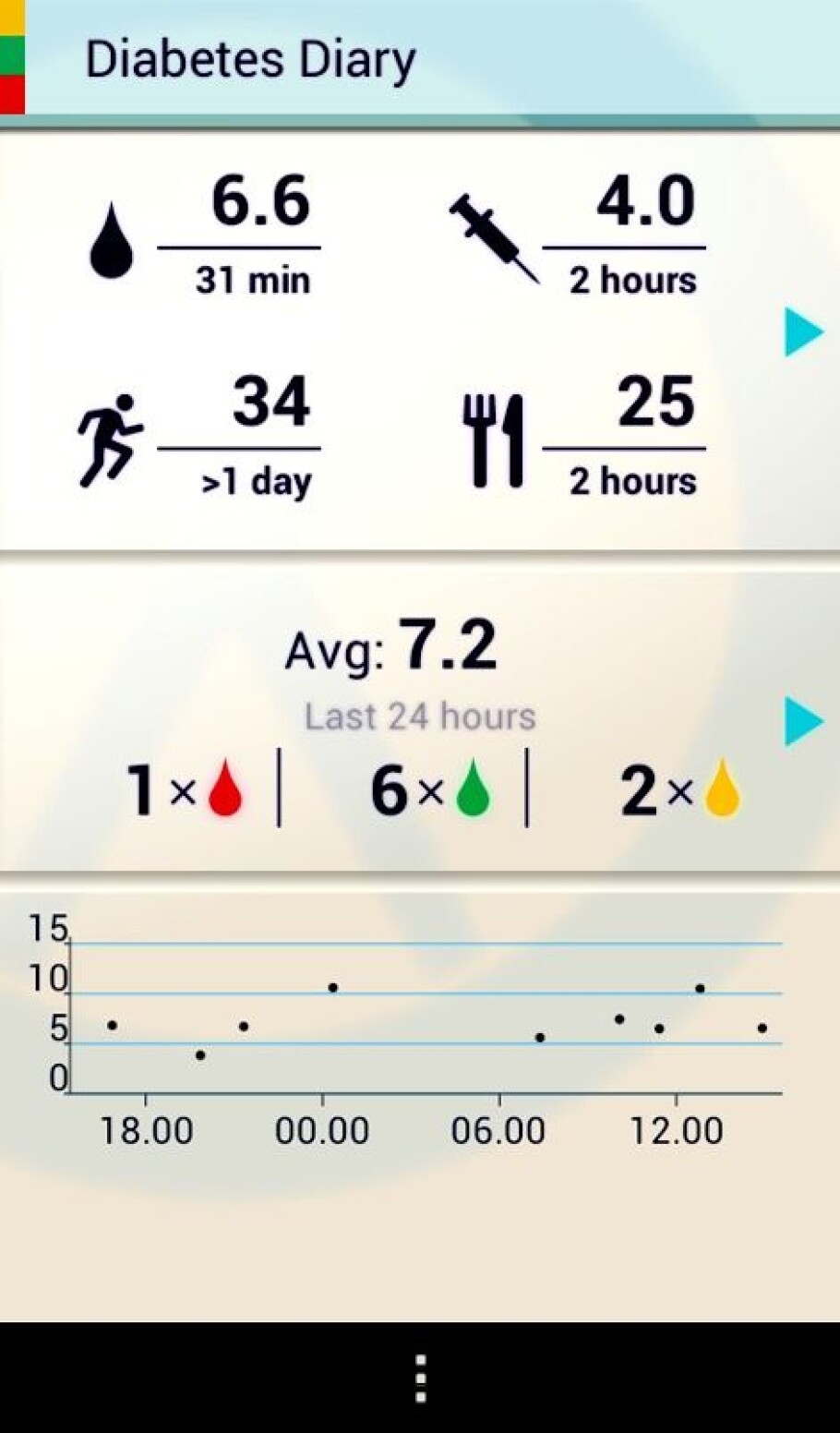

PhD student Meghan Bradway, her advisers and cooperation partners, have analysed the user logs of 101 people with diabetes, who used an earlier version of the Diabetes Diary app.

Researchers have recently published an article on the subject where they conclude that the traditional way of conducting randomised controlled studies (RCT) is not suitable for researching mobile health technology.

The work was carried out as part of a project financed by the Norwegian Research Council.

“Traditional research methods are based on the analysis of before and after results, for example, when one group is given a pill containing medicine and another a placebo. Thereafter, one looks at who it worked on. Randomised controlled studies are considered a golden standard within medical research, but with the introduction of mobile health technology, researchers should also use new methods,” says Eirik Årsand, professor and project manager at the Norwegian Centre for E-health Research.

Many factors when using technology

Randomised studies do not take into account that patients have mobile health technology with them wherever they go – collecting and using information from activity trackers, smartphones and medical devices to help them self-manage their health.

“Since there are so many factors, it is complicated to analyse. It depends on which smartphone or smartwatch the user has, whether they even want to use health apps or fully understand all the collected information. RCTs do not give all the answers and sometimes no answers at all when users approach mobile health technology so differently,” says Meghan Bradway and then adds:

“If we are going to understand what is happening, we need to analyse each click on the screen.”

Reduced long-term blood sugar levels

Based on the usage logs from a recent study, the researchers divided the patients who received mobile health tools, into two groups.

Those who used the app a lot, occasionally or never. Of the 101 patients with access to the digital diabetes diary with wireless transmission of blood sugar data, 29 did not use the system at all, 11 used it occasionally and 61 used it a lot.

While not statistically significant, the results were astonishing: The 61 long-term users reduced their blood sugar levels by 0.86 per cent on average.

“This shows what can be discovered when new methods are used to analyse what happens when patients start using this technology. Not only did we find that the amount of app-use can affect one’s health, there were also great differences in how various features of the app were used,” says Meghan Bradway.

Those who were active, reduced their blood sugar levels the most

The blood sugar values of the patients were automatically recorded in the app. They had to manually record what they ate and how physically active they were.

They could set personal goals and search for information about diabetes in the app. Of the 61, who used it the most, there were two sub-groups: one mainly recorded food and physical activity and the other mainly used the blood sugar feature and reviewed previous data in the app.

“When we plotted the two groups and saw how their long-term blood sugar developed during the year, we noticed that those who spent the time to record food and physical activity reduced their long-term blood sugar levels more than the second group. We wouldn’t have found this out if we hadn’t looked at the logs on the app and analysed user patterns,” emphasises Årsand.

Diet and physical activity

Mobile health technology could, for example, include body sensors that send information to your mobile phone about your blood sugar.

You could have a physical activity tracker in your watch or a Fitbit watch that also logs your sleep pattern. For diabetes patients, medication devices can even send information to apps or other devices automatically, making it easier since they do not have to remember to record it themselves.

For patients with diabetes type 1, diet and activity are often important factors in coping with the disease.

Mobile health technology can help them self-monitor their activity or what they eat. Also, health personnel and researchers can help the patient monitor this and even adapt treatment based on the data.

“By analysing the users’ logs, you can find out so much more than is possible from just using questionnaires and medical measurements, taken only during consultations a few times a year. It’s stated in black and white whether the users are physically active, not just what they can remember they have done,” says Bradway.

Mobile app training

There could be many reasons why some patients manage to reduce their long-term blood sugar levels.

They may be more motivated or have the personality and drive that makes them use their mobile health technology more actively. Psychological factors also play a role for those with significant health problems.

Since everyone is different, the technology should be adapted to motivate the users and not make them feel controlled.

“For example, the completion of a smartphone training course before using the app to cope with health conditions, could be a good idea. Whilst, those who already use such apps could receive even more information about their own health,” Årsand suggests.

More research is being conducted

The Norwegian Health Service will gradually become drowned with data from apps and sensors that patients use independently, but it is not fully ready for this.

Researchers at the Norwegian Centre for E-health Research are now conducting a study to test how diabetes patients can share their data with health personnel during consultations.

“Today, they can bring their apps, such as the Diabetes Diary, to show health personnel, but in the project they can send the data via the Internet during a physical consultation or a remote consultation. It will be exciting to see how this develops in the future,” say Bradway and Årsand.

—————

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no