This article is produced and financed by the Institute of Marine Research - read more

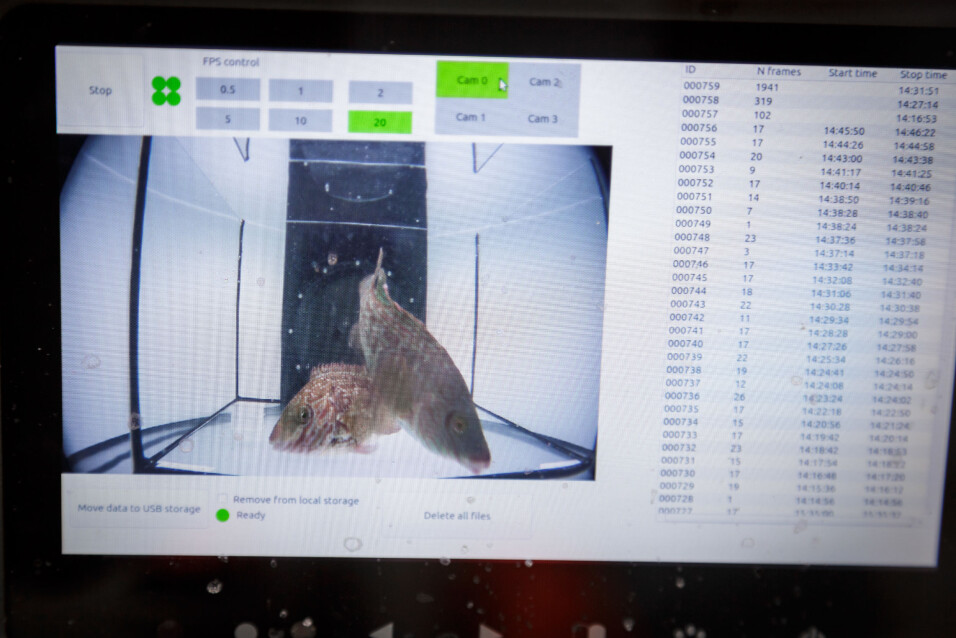

Facial recognition of fish is just one way artificial intelligence is used in marine research

But there are many other possible applications.

Even just a few years ago, a camera system to identify fish would probably have seemed like science fiction. And who wouldn't want a robot to perform time-consuming and monotonous tasks during long voyages?

Artificial intelligence is here to stay, if we are to believe the researchers Nils Olav Handegard, Ketil Malde and Howard Browman. In an article collection that precisely deals with machine learning and marine research, the Institute of Marine Research is represented by two articles on the possibilities offered by machine learning.

"There is great potential for machine learning to improve and expand the scope of marine research, by identifying underlying patterns and links," says Browman.

He believes that machine learning is particularly useful when dealing with large quantities of data that are hard to make use of in other ways.

"The possibilities offered by machine learning make it inevitable that it will be used in marine research and marine resource management," he adds.

Large data sets

The branch of artificial intelligence known as machine learning is the one that provides most opportunities for marine research.

The researchers have drawn inspiration from the structure and workings of the human brain in order to find the best way to train algorithms. This allows you to feed in large data sets and discover patterns that would otherwise have remained hidden or hard to detect.

"This technique can be used to find patterns in large volumes of historical acoustic data, which is difficult to do manually," says Handegard.

Thanks to technological progress and greater computing power, it has become cheaper to build up large data collections. Consequently, the use of machine learning will only increase, according to Ketil Malde.

The Institute of Marine Research is in a unique position to introduce new methods. We have the technical expertise, the large volumes of data and, perhaps most importantly, the big questions that need answering.

More possibilities

However, species recognition using images is just the start. Once the technology is in place, it is possible to monitor fish over extended periods, and for example, study how the climate and other factors affect their patterns of behavior.

At the Institute of Marine Research, machine learning has been used to analyze otoliths and fish scales. Otoliths are found in the ears of fish, and together with their scales they tell us a great deal about the ages and life stories of the fish – in fact, they're rather like tree rings.

Machine learning has proved an effective tool in this work, with its accuracy sometimes matching human analysts.

"Although ideally you want that kind of accuracy, there are also many applications in more limited scenarios," explains Handegard.

He points out that a function to weed out irrelevant data, for example, can be just as important. Partly because it saves time, but also because it makes the scientists' work more rewarding.

"By reducing the number of trivial routine tasks, it allows the human experts to concentrate on more interesting and rewarding work," says Ketil Malde.

Not all plain sailing

In other words, using machine learning in marine research has the potential to both increase efficiency and free up the time of researchers.

But there are still some challenges to overcome.

"The technology has enormous potential, but you need large quantities of data to 'train' the models. Often there is more work involved in collecting and organising the data than in developing the system itself. In order to exploit the work that has been done, we must start using these systems in our research and advisory activities. That requires good cooperation across the institute," concludes Malde.

References:

Ketil Malde et.al: Machine intelligence and the data-driven future of marine science. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsz057

Cigdem Beyan & Howard I Browman: Setting the stage for the machine intelligence era in marine science. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsaa084