This article is produced and financed by University of Oslo - read more

The world with viruses: The coronavirus crisis is increasing the risk of political instability

“I believe that there are many leaders around the world who are currently at risk of putting a foot wrong,” says Tore Wig. As a political scientist he has been conducting research on the reasons for the collapse of regimes.

Over the last few years Tore Wig, an Associate Professor at the Department of Political Science at the University of Oslo, has been involved in designing a comprehensive collection of data on democracies and dictatorships. He possesses expert knowledge about what makes individual forms of governance successful, while others fail and perish.

Accompanied by two other researchers, Vilde Lunnan Djuve and Carl Henrik Knutsen, Professor Wig has collated information about how long such regimes last, how they break down and why they collapse. Their list dates back to 1789.

“We have also linked this data to political and economic development trends in several different countries. One of the main findings of our research and that conducted under another research project is that economic crises often result in the collapse of regimes,” says Professor Wig.

Financial crises led to political protests

According to Professor Wig, most armed rebellions in recent times have benefitted financially from poverty. The upsurge of IS in Syria and the Sunni areas in Iraq was dependent on being able to use black market oil money to entice unemployed young people. The Arab Spring came about when young people without jobs took to the streets. The financial crisis in 2008 resulted in high unemployment and political protests in countries such as Spain and Greece.

Based on his research on political instability, Professor Wig maintains that there are good reasons why we could start to see social unrest and political upheavals as a result of the coronavirus outbreak.

“We are talking about simple mechanisms: when people start to suffer, they have less to lose from causing unrest, ending up in prison and joining a local militia.”

“If you risk losing your job if you protest in the streets, the chances of rebellion are less likely. We are also talking about the fact that rapid economic decline creates frustration and anger because people’s visions of the future clash with reality. Hope is replaced by resentment,” says Wig.

An impossible dilemma

“Heads of state around the world are now having to perform a challenging balancing act. Public health needs to be weighed against business interests and jobs. The health services should not be overloaded, while at the same time the economy needs to be protected. It is like having an impossible dilemma: the more we try to stem the tide of the virus, the greater our economic problems will be at the other end. And the more we place priority on jobs, the more the virus will grow,” says the professor.

“Our research shows that it is hard for political elitists to predict what might trigger a rebellion and when it will happen. I believe that many global leaders are now at risk of putting a foot wrong,” he says.

He also refers to the fact that dictators and political leaders in countries with weak democratic systems often take advantage of crises to introduce a state of emergency and consequently new legislation.

Professor Wig points to Hungary, where Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has introduced a state of emergency with no time limit, which gives him powers to dictate the country’s legislation. Similarly, Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Nethanyahu is in the process of closing the country’s courts.

“Several global studies have looked at how states of emergency are linked to the introduction of dictatorships. States of emergency, crises and transitions to authoritarian regimes often go hand in hand,” says Professor Wig.

Democratic decline

The Global State of Democracy 2019 report shows that half of the world’s democracies are being eroded. The new, ERC-funded research project, ELDAR, will address the rise of authoritarian regimes. Tore Wig is a member of the research team. Even though he is worried about democracy’s decline in status, he emphasises that any upheavals resulting from the coronavirus pandemic can just as easily affect autocratic regimes.

“A dictatorship could also fail in its handling of the pandemic. Any faulty steps could cause people to mobilise and maybe even result in democratisation as well if the incumbent regime is overthrown.”

The coronavirus crisis is actually increasing the risk of political instability. In response to a request, Wig presents a list of states which he will be following closely during the time ahead:

- Bolivia, because there has been considerable unrest in the country, even well before the coronavirus outbreak occurred. Evo Morales resigned as president following pressure from the armed forces and protesters. Heads of state in other Latin American countries have called this a coup. Recently there have also been major protests because people want to return to work. So far there have been few deaths related to the coronavirus in Bolivia, so people are not really perceiving the virus as a real threat. So when they are not allowed to go to work, people take to the streets.

- Brazil, because President Jair Bolsonaro is playing down the severity of the coronavirus, and the pressured situation is causing increased discontent with his leadership. If the crisis escalates, more dramatic things could rapidly occur in this country.

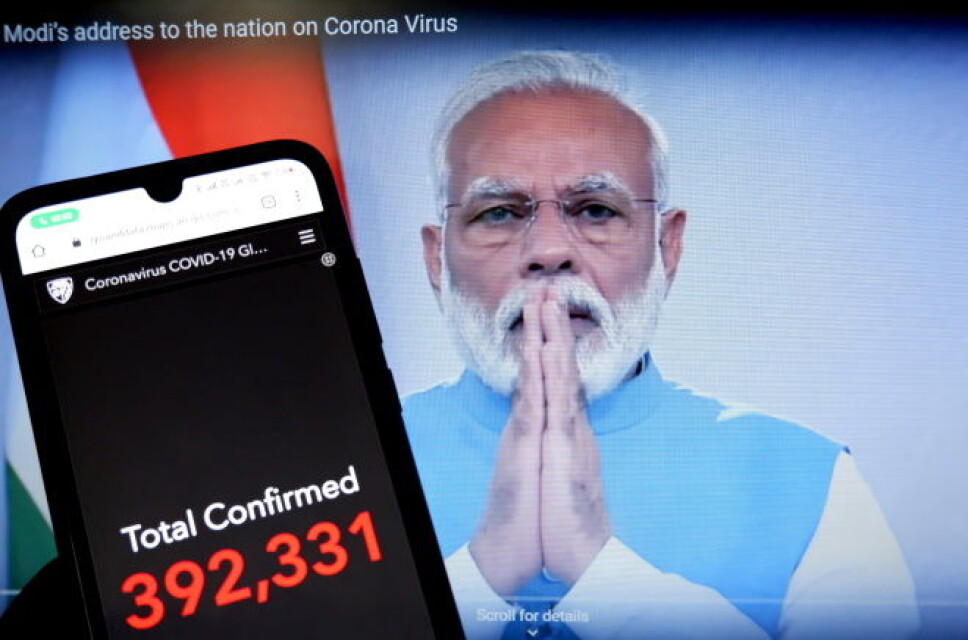

- India, because there have been massive protests against Prime Minister Narenda Modi after the new Citizenship Act was introduced on 11 December. Critics of the Act claim that Modi, who represents the Hindu nationalist BJP party, is marginalising the Muslim share of the population. There are many historical examples of heads of state who use crises to fuel existing ethnic tensions in a country.

- Iran, because the authorities have so far not handled the crisis very well. Many people have died, a lot of misinformation has been provided, and confidence in President Hassan Rouhani appears to be low. Several members of the political elite in Iran have been infected by the virus, including the Vice President and the head of Iran’s Emergency Medical Service. This is a country where there has already been a certain amount of political instability, and the coronavirus situation – combined with low oil prices – is creating a potent mix of factors which could lead to further unrest.

Democracy - autocracy

One common feature of the countries on Professor Wig’s list is that they are nations with weak state capacity which simultaneously lack democratic tools.

“Many people believe that pure dictatorships, such as China and Singapore, have the best conditions for dealing with this type of crisis”, he says.

“In Wuhan we have seen brutal but extremely effective closures, with people being dragged out of their homes and placed in isolation, or where the doors of blocks of flats hit by the infection have been welded shut by officials. Singapore has taken advantage of extreme digital surveillance in order to control the spread,” says Wig.

However, he is able to refer to just as many examples of countries which have used democracy to deal with the crisis, in a quick, convincing manner. He says that democracies generally have the advantage of being transparent, the media are able to criticise government policy and people believe what politicians tell them.

“One example is Taiwan, where there have been almost no deaths. This is the result of infection tracking and home quarantine, combined with general confidence in Taiwanese society and respect for the country’s politicians. The same applies to South Korea where we have seen a spirit of voluntary cooperation similar to that in Norway."

Little unrest on the home front

The government’s ban on travelling to holiday cabins has created a certain amount of turmoil in Norway’s public discourse. Questions have also been raised about the differences between the recommendations of the Norwegian Institute of Public Health and the strategy adopted by Norway’s politicians.

The proposal to introduce comprehensive emergency legislation which would abolish the Storting’s role as a legislative power was met by criticism from several quarters.

Wig believes that dissent is a healthy sign when we consider our democratic system. Equally he believes that there is considerable public support for the Norwegian measures.

“This crisis has shown us that the Norwegian state is competent and that our bureaucracy is working well. It comes as no surprise that Norwegians have great confidence in the experts. Our political leaders are wise to seek the support of the experts, and the Institute of Public Health has retained its academic integrity,” he says.

Wig emphasises that the economic situation and health policy are factors which the government needs to take into account, and these do not fall under the mandate of the Institute of Public Health.

“In the same way we can look at closing the schools as a measure implemented by the government, not exclusively to limit the spread, but also so that the population can feel safe and looked after,” says Professor Wig.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no