An article from KILDEN Information and News About Gender Research in Norway

Online computer games force women into the closet

Women conceal their gender in order to avoid harassment in the gaming community and in the outside world.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Female gamers choose male avatars and gender-neutral names. They choose not to talk when they wear headsets, or they use a voice changer. They refuse to answer personal questions.

The consequence of revealing your gender may be extensive harassment, sometimes also outside game world.

A new survey on sexual harassment in online computer games shows that approximately half of the women have actively concealed their gender to the gaming community and their fellow players.

According to a male gamer who was interviewed in the survey, indicating that you’re a female player is like asking for extra attention.

“You’re not only heterosexual until proved otherwise, in many circles in the game world you’re also male until proved otherwise,” says Kristine Ask.

“Some circles actually force their female players into the closet.”

Ask is a self-confessed gamer and lecturer at the Department of Interdisciplinary Studies of Culture at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). Together with researcher Stine Helena Bang Svendsen she recently published the report "Bug or feature?" Seksuell trakassering i online dataspill (“Bug or feature?” Sexual Harassment in Online Computer Games).

Both being female gamers, they have experienced much of what the report uncovers.

“The project came about as a result of a discussion concerning how we perceive the use of abusive words in the computer game World of Warcraft differently. So this is a concern which comes from inside the gaming community.”

Half of the gamers are girls

There is a strong stereotypical notion that most gamers are young boys. This is in spite of the fact that, according to The Entertainment Software Association, 48 percent of the gamers are women. Moreover, most of the gamers are adults, not teenagers.

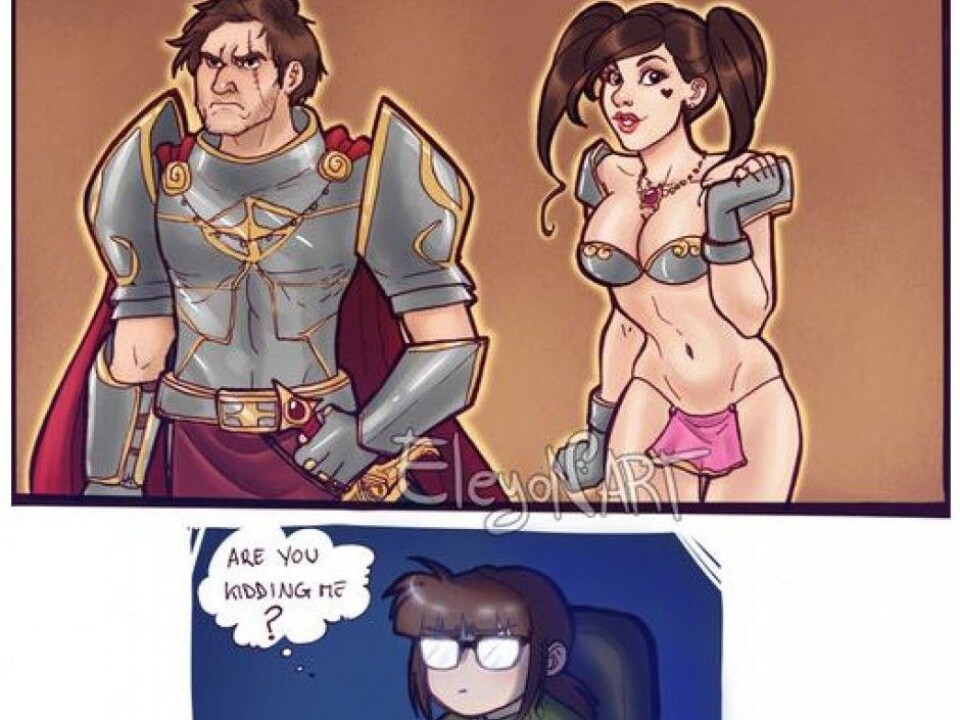

Part of the explanation to why computer games are still regarded as boys’ toys is, according to the researchers, the design and the marketing of the games. Although the typical idea of the gamer is a young, pimply male nerd, the game world is in reality excessively masculine, according to Ask.

The report describes game fairs where computer games are promoted by half-naked women without any clear connection to the product. Half-naked women are also often depicted on the game covers.

The characters in the games are normally men. These male characters are often equipped with armour covering the entire body, while the female characters’ armour may look like a bikini. The women are sexy, with huge breasts, while the men are white and well built.

The plot normally revolves around the white male warrior who must kill a large number of people with a different skin colour. Eventually, he gets his reward, which is a beautiful, sexy woman.

“A consequence of online games with sexist design and stereotypical representations is a lower threshold for sexual harassment,” says Ask. However, she emphasises that a change of the design alone is not enough to solve the problem.

Harassment is common

Ask and Svendsen’s survey received 935 responses. Moreover, they have carried out qualitative interviews with three women and five men.

The participants are between 18 and 40 years old, and they are all active gamers. Two thirds are men, while one third are women.

Nearly 80 percent of the participants have seen words like “gay” and “retard” being used in an abusive manner. Just over half of them have seen the words “whore”, “pussy” and “cunt” being used, in addition to “rape” and other expressions which involves threats of violence.

However, the use of sexually abusive words is not necessarily the most important find. What is interesting is the gamers’ explanation to why these words are being used.

“Half of the participants didn’t regard it as a problem; to them it is just a part of the game. The other half regarded it as a problem,” says Ask.

“It is not a surprise that more women than men think of it as a problem.”

Destroys the joy of gaming

Ask thinks it is important to understand those who defend the harassment that is taking place. According to their arguments, the harassment is part of the culture and the fantasy. If you take offence in being called whore or retard, you haven’t understood the gaming culture. If you refute these expressions, you destroy the fantasy and the joy of gaming.

“For many people, entering a role which is not socially accepted in real life seems to contribute to the joy of gaming,” says Ask

“I can understand the appeal. Having a place where you can do and say anything you’d like without having to fear the consequences gives a fantastic sense of freedom.”

One informant thought it would be absurd to try to change the use of abusive language as long as the game revolves around killing the other virtual character. Since killing someone in a computer game has no repercussions, neither should harassment, since:

“That world is so different, it’s a fantasy. I hate violence in real life. But I love explosions and chain saws on film, because it is great fun, and it provides a safe way of giving vent to your darker fantasies.”

Harassed also in the real world

“But these arguments don’t hold water,” says Ask.

“The harassments are transmitted from the fantasy world of the gamers into the real world.”

One of the men in the study told a story about a girl who was not a very aggressive player, but she received a lot of attention because she was a girl. She had a delicate voice and sounded sweet. A few of the others in the game group found her Facebook profile and some photos of her. When she left the group as a result, they tried to search for her.

“In light of such incidents, claims saying that the harassment stays within the game don’t seem very trustworthy,” says Ask.

Moreover, more than half of the survey participants have heard about people who have been chatted up in online games. 15 percent had experienced being asked through an online computer game whether they wanted to meet in order to have sex. 36 percent of the men and as many as 87 percent of the women found it annoying.

Sexualised hate campaigns

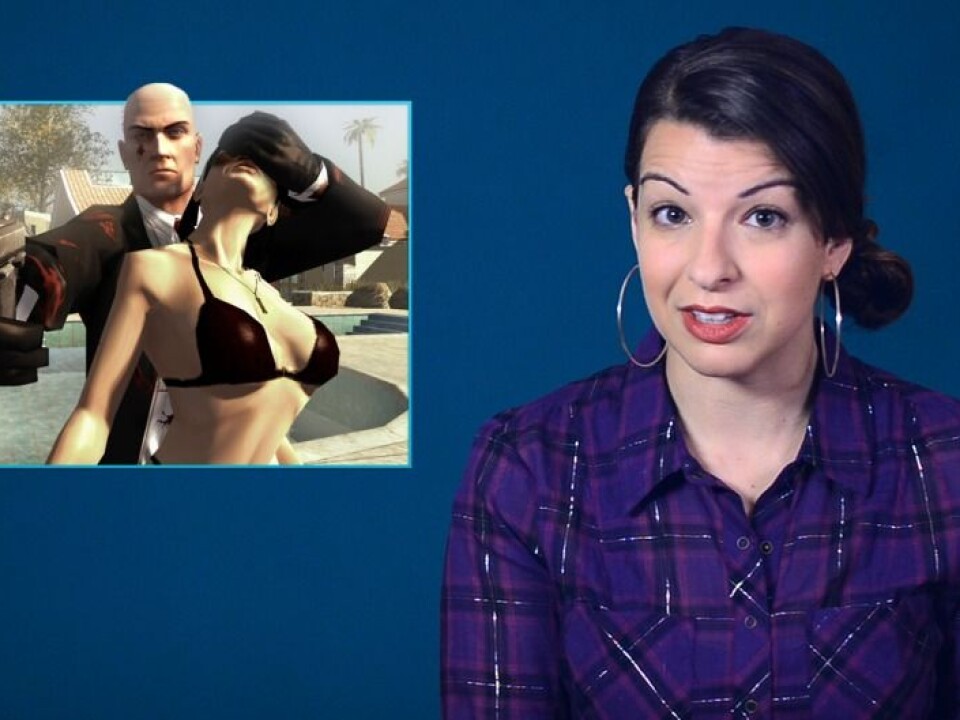

In their introduction, Ask and Svendsen presents two extreme cases that clearly illustrate the point they’re making in the report. Game critic Anita Sarkeesian and game creator Zoey Quinn have both received death threats which forced them to leave their homes in August 2014.

Sarkeesian was threatened due to her feminist critique of the representation of women in computer games, while Quinn received threats after her ex-boyfriend accused her of offering sex in return for a positive review of a game she had recently developed.

The two women were exposed to enormous hate campaigns both online and in life offline. For instance, Sarkeesian repeatedly received manipulated photos of herself in the mail where she was pictured being raped by known game characters. Moreover, a game was developed in which every click on her face represented a punch.

The extent and the coarseness of this harassment has given rise to the term «Anita’s Irony»: Online discussions on sexism and contempt for women quickly result in an excessive amount of sexism and contempt for women.

The debate concerning women and the game culture has been boiling over the last months under the hashtag #gamergate. This is partly due to these two cases.

“Gamergate and the harassment of strong female game personalities are much worse and much more extensive than what we have studied,” says Ask.

“But it proves our point that what goes on in the game fantasy is not isolated from the real world.”

The harassment of the two women is clearly gendered. The threats are sexualised and the comments revolve around looks and the women’s bodies. And it is explicitly anti-feminist.

And yet, despite this harsh harassment: even in gamergate, there are differing opinions as to whether this type of harassment must be accepted as part of the game or whether it should be opposed.

A changing gamer identity

According to Ask, the debates show that the gamer identity is changing.

Online gaming has become so common, which makes it more difficult to hold on to a subcultural identity.

“I believe many male players feel that this space of fantasy is threatened,” says Ask.

“The gamers were never as homogenous as they thought they were. But until recently, those who were not white, heterosexual men remained quiet. An important effect of the sexual harassment which is going on in the game world is that it maintains the existent myth that gamers equals heterosexual men.”

The gamers and researchers Ask and Svendsen belong to the 50 percent who are in favour of a change in the game culture. They think the avatars should be less gender stereotypical and more diverse, the plots should be more varied, and the opportunities for reporting bad conduct should be better.

Moreover, they wish the media would become better at considering game culture as proper culture, not only as subculture.

“Although the debate concerning gender and computer games has exploded over the past years, it has received little or no attention in Norwegian media. This strengthens the notion that gaming is different from other media. Like other cultural expressions, gaming needs to be discussed within the public sphere. The discussion shouldn’t be left only to those who have an enthusiasm for gaming.”

Critique creates better games

Although nearly 60 percent of the survey participants had noticed sexist and stereotypical representations of gender in the games, only 15 percent had thought of the game design as racist.

According to the researchers, people’s competence at recognising ethnical stereotypes or stereotypes based on race and the universalisation of whiteness is relatively low in Norway and in the Nordic countries.

“There has been an on-and-off debate concerning gaming and gender over the past twenty years. The fact that there has been a debate has made more people aware of the problem,” says Ask.

“We haven’t had a similar debate on race and ethnicity in Norway yet, but hopefully that will follow.”

According to an American survey, 80 percent of the game characters were white and the representation on non-white characters are as stereotypical as the big-breasted, half-naked female avatars.

“The good news is that the critique has had an effect,” says Ask.

“Particularly the independent game developers seem to understand the importance of inclusion. So objecting to established practices does help.”

Translated by: Cathinka Dahl Hambro