THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY the University of South-Eastern Norway - read more

Warmer climate enables ticks to survive in the high mountains

Researchers have found ticks living at 1000 meters above sea level in the Norwegian mountains and say that a warmer climate is the reason.

The discoveries have been made at two different locations in Southern Norway, and Nicolas De Pelsmaeker from the University of South-Eastern Norway believes that ticks may be found at even higher altitudes.

“Before this discovery, ticks had not been found at altitudes higher than 583 masl, so a dramatic development has taken place over a short period of time, and we do not know where it will stop. Further studies can tell us if ticks are present even higher up in the mountains,” says De Pelsmaeker.

He publicly defended his doctoral degree in Ecology on 5 March.

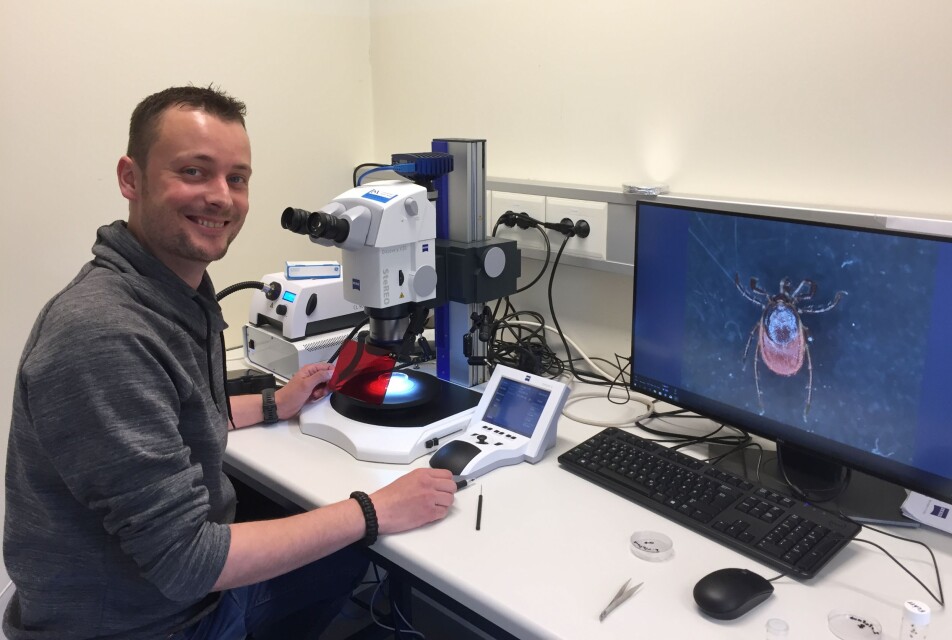

De Pelsmaeker has mapped the prevalence of two different types of tick: Ixodes ricinus (castor bean tick) and Ixodes trianguliceps (vole tick). The investigations took place in Lærdal (Vestland County) and at Lifjell (Vestfold and Telemark County).

Tick larvae on small rodents

The researchers captured well over 3500 small rodents during field work in the mountains. They found over 15,000 tick larvae on these. Larvae and nymphs are dependant on small rodents and other small animals, while adult ticks can attach themselves to large animals. Both nymphs and adult ticks can attach themselves to humans.

It is well documented that small rodent populations vary in the mountains. De Pelsmaeker is unsure how this will affect young ticks and larvae. Because variations in small rodent populations increase the higher in the mountains you get, this may become a limiting factor in relation to how high ticks are able to establish themselves.

De Pelsmaeker believes that regardless of the findings from the doctoral work, we need to readdress the risk of disease posed to humans and animals in the mountains.

More animals and humans will be bitten

“Many Norwegians spend a lot of time in the mountains. An increase of ticks at greater heights will increase the risk of being bitten, and therefore also the transmission of tick-borne diseases.”

Between four and five hundred cases of infection caused by the Borrelia burgdorferi bacterium are diagnosed in Norway each year. This bacterium causes the disease borreliosis, Lyme disease, or Lyme borreliosis, and the bacterium is transmitted via tick bites.

“Sheep farmers, goat farmers and anyone who grazes their cattle in the mountains will also be able to notice that there are more ticks at higher altitudes,” says De Pelsmaeker.

“We already know that morbidity and mortality among sheep can be caused by tick-borne anaplasmosis. The social and economic consequences of tick-borne diseases have so far been limited to lower-lying areas, but prevalence at higher altitudes combined with a longer tick period may lead to increased damage to the livestock industry,” says De Pelsmaeker.

He also fears that the role of livestock as tick hosts could contribute to more ticks in the mountains and that ticks could spread to even more areas.

Carried by migratory birds from the south

There are approximately nine hundred different species of ticks in the world. At least eleven of these have been recorded in Norway. Unfortunately, that number could increase in years to come. Migratory birds carry along other types of ticks when they arrive in Norway. In the past, these species have not been able to survive here, but a warmer climate enables airborne ticks from southern regions to bring tropical diseases to Norway.

Ticks survive (almost) everything

Most people will say that ticks are a real pain in the neck and we are better off without them. However, De Pelsmaeker believes that all animals have a place in nature, and even he is fascinated by the tiny creature.

“Ticks are capable of many things, but there is something that it really excels at, and that is its ability to wait. If no host is available or the air is too cold or dry, it will simply wait. For a very long time if necessary. The castor bean tick, which is the most common species in Norway, can live for up to seven years, and ticks have been known to live as long as twenty years.”

De Pelsmaeker says that ticks are incredibly tenacious and are able to survive extreme environments over long periods of time. Experiments have shown that when completely immersed in water, female ticks can live without air for up to thirteen days while showing no signs of weakness. Newly hatched larvae have actually survived as long as a month and a half immersed in water.

Surviving winter in the mountains

But what about the harsh winter in the mountains? Won’t that put an end to the ticks?

De Pelsmaeker was also unsure about this. That is why he set up a survival experiment during the 2019-2020 winter. He placed ticks in small tubes made of fabric so that they would not be able to escape but would still be affected by external environmental factors. The tubes remained outdoors throughout the winter and were checked once the snow had melted. The researchers found a lot of live ticks when they checked the tubes.

“We see high survival rates at all altitudes,” says De Pelsmaeker. He emphasises that the results are preliminary and not yet published, but they show that ticks can withstand both low temperatures and long periods without food.

Vestland ticks remained active in the fridge

“They hibernate when the temperature falls below five or six degrees Celcius. They virtually stop all their bodily functions. As soon as the temperature rises, they become active again. I have been testing this with ticks in my fridge at home for several months, and it actually turns out that castor bean ticks from Lærdal behave differently than the ticks from Lifjell,” says De Pelsmaeker.

The Vestland ticks remained active much longer in the fridge before going into hibernation, while ticks from Lifjell went into hibernation much more quickly. De Pelsmaeker does not know what actually causes this.

Life-saving tick saliva

No matter what you may think of ticks, the little creatures may one day actually prove to be of use to humans. Researchers have discovered that tick saliva contains a large amount of complex organic molecules. Some of these have the function of preventing the host’s blood from clotting. Other substances enable ticks to almost superglue themselves to the host.

“Because ticks often drink blood over the course of several days, they do not want to be detected by the host. Therefore, special molecules are also present in the saliva that prevent skin irritation and itching,” says De Pelsmaeker.

“There are several promising results related to the substances found in tick saliva. Perhaps the saliva may one day be used in the treatment of human diseases,” De Pelsmaeker says.

The molecules that prevent irritation and itching could be useful in the prevention and treatment of Myocarditis. Myocarditis is an inflammation of the heart muscle that often affects young people under the age of 30 and can lead to heart failure. Researchers are also looking at whether the substance that enables ticks to attach themselves to their host can be used to glue together human skin after operations, on wounds and injuries, and prevent critical blood loss.

“Mother nature is an endless classroom for those who are curious and who want to observe and discover,” says Nicolas De Pelsmaeker.

Reference:

Nicolas De Pelsmaeker: Altitudinal Distribution and Host- Parasite Relations of Ticks in Norway, USN Open Archive, 2021.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

See more content from the University of South-Eastern Norway:

-

Urban development involves much more than buildings, roads, and green spaces

-

School refusal: 8 out of 10 kids perceive school to be an unsafe place

-

We become less polite when we are shopping

-

Humans are 99 per cent the same, yet so different

-

Norwegian researchers reject that Northern Norway is part of the Arctic

-

Community response is vital for social recovery from mental health and substance abuse issues