THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY the Western Norway Research Institute - Read more

Your mobile phone is a climate culprit

The number of smartphone users is nearing half the world population. This is not great news for the planet.

On average, Norwegian households purchase a new mobile phone each year. By the end of 2021, half of the world’s inhabitants will have a smartphone.

“A single mobile phone is not very harmful to the environment, but whenever a product is produced in high numbers, there will be problems. The high pace in which we replace our smartphones, adds to the negative impact,” says Hans Jakob Walnum. He is a researcher at Western Norway Research Institute, and has recently looked into the environmental consequences of the ever-growing numbers of smartphones in the world.

Walnum applied a life-cycle perspective, which means that he included the environmental effects caused throughout the product’s life, starting at the factory and ending at the garbage heap.

“By including the entire lifespan, we avoid a common mistake in comparing products: leaving out significant sources of impact. The method requires a bit of detective work on the part of the researcher. We must scrutinize the origin of various sub-components and ask the industry how how they distribute their goods to customers across the world.”

The researcher also needs to work out what smartphone users like you and me do with our phones every day - and for how long, not to mention where our electronical waste ends up.

“Production is one thing, but the entire life of the smartphone must be examined in order to gain a complete picture,” Walnum says.

Lots of different metals

Let’s start with the gorgeously sleek and colourful touchscreen. As your fingertip glides elegantly across the glass surface, you might want to thank a handful of rare-earth metals that were most probably dug out of the ground somewhere in China.

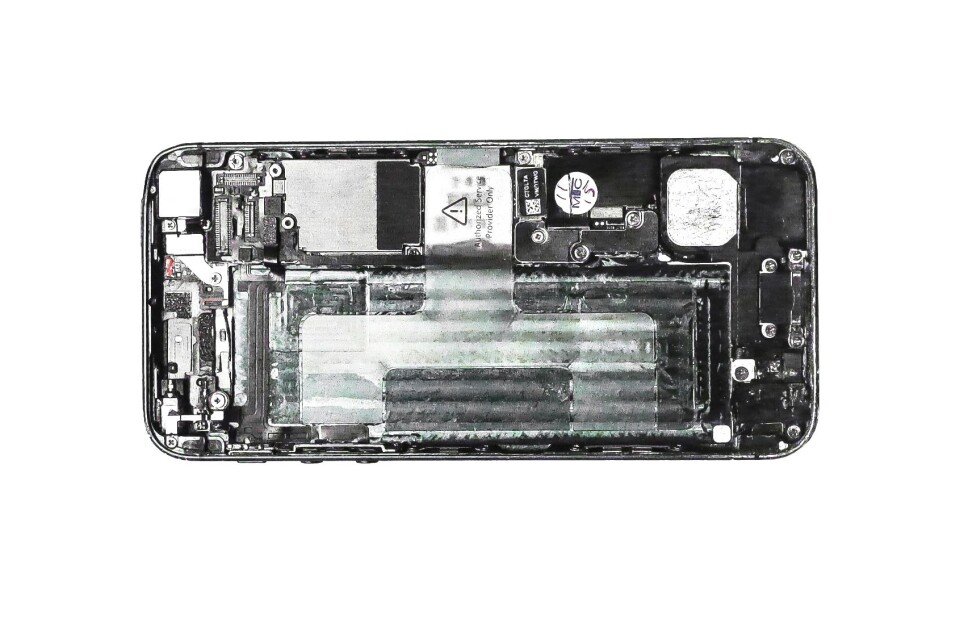

The list of substances that are required to make your phone work, might take you by surprise. Whereas a familiar metal, aluminum, is most common on the phone's outside, the inside offers a whole range of less known metals, including neodymium, praseodymium, and dysprosium. This is a trio of metals that provides sound and vibration.

Your phone’s battery relies on cobalt, graphite, and lithium. Inside the processor, there is silicon with a long list of additives, such as phosphorous, antimony, arsenic, boron, indium, and gallium.

Did you know that an average iPhone contains almost half of the periodic table of elements?

Miserable mines

“Unfortunately, these resources are not renewable, meaning that they are gradually depleted. Only a tiny share of what is inside a scrapped smartphone is recycled and put back into use,” Walnum explains.

Most of the chemical substances needed to produce a smartphone, are extracted from mines in South America, Africa, and Asia – some of them notorious for dire social and environmental conditions.

A well-known example is Congo’s cobalt mines where children work under extremely dangerous conditions. In 2019, a group of Congolese parents whose children had perished, took legal action against American technology companies.

A multitude of production sites

As you are probably beginning to realize, the family tree of a smartphone is complex. Even if we move on from the various substances and concentrate on the individual components that make up a mobile phone, we would be hard pressed to say it comes from a specific factory in a single country.

“A typical mobile phone contains components from something like five factories on three different continents,” says Walnum.

Most manufacturers both produce and assemble their phones in Asia. This leads to a great deal of transportation, which causes high carbon emissions. These factories also spend quite a lot of energy from non-renewable sources, meaning that we must add carbon emissions to our calculations.

Metal cleansing also requires great quantities of water, and the process renders the water harmful to the environment. In addition, all the regular emissions associated with transporting goods must be counted.

Flying is the new transport mode

Since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, Western countries have become more aware of the vulnerability associated with products being manufactured in Asia. Whether our heaps of freight goods travels to us, from thousands of miles away, in a container ship or by plane, should perhaps be added to our list of worries.

“I have been informed that air freight has replaced ship freight as the dominant mode of transportation, which came as a great surprise,” Walnum says. The reason for this shift is a sharpened competition between manufacturers.

The problem is that emissions literally skyrocket the minute you put smartphones on a plane:

“In terms of greenhouse gas emissions, air freight is about 100 times worse,” Walnum explains.

Clouds and data centers

You have probably noticed that as smartphones has become faster and better, your range of use has widened. On an ordinary day most of us stream videos, listen to podcasts, and use social media. We text, we check our e-mail, take pictures, read the news – and so much more.

Added up, and in the long run, all this screen time adds to the world’s climate emissions:

“Streaming contents for an hour a day equals an annual carbon emission of 10 to 20 kilos of CO2-equivalents,” says Walnum.

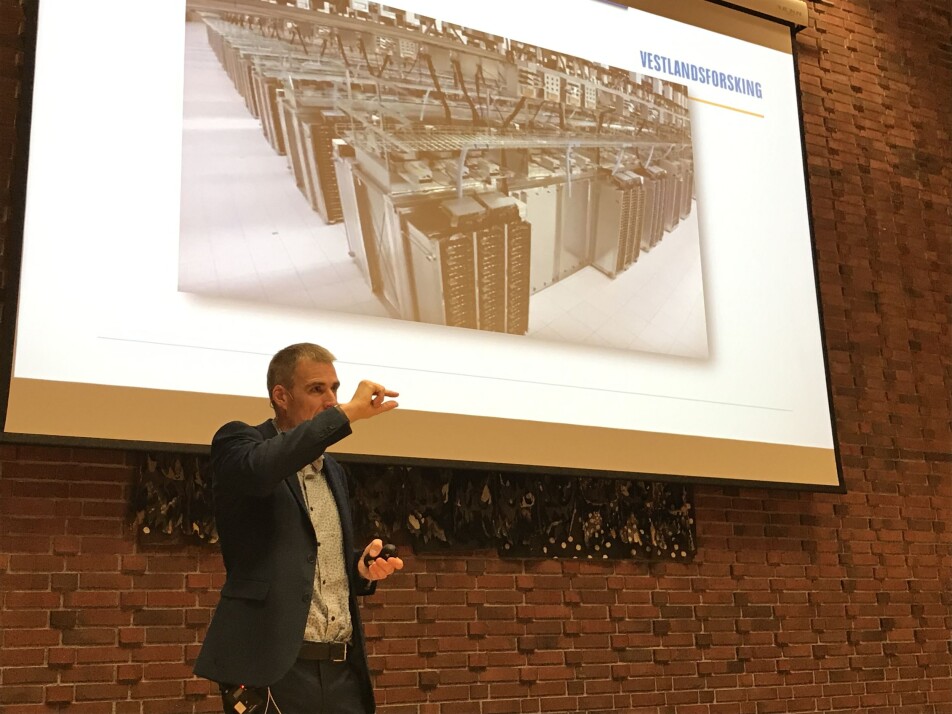

When you store content on your mobile, it means storing it in the cloud. The physical manifestation of the cloud is actually a giant data centre somewhere in the world. In such halls, large line-ups of computers are continuously at work, fueled energy that may either be renewable or non-renewable, depending on the location, and leading to carbon emissions. The more we store and stream, the larger the carbon emissions.

Streaming boom

The exact size of the environmental footprint of everyday mobile usage is hard to determine. This is because the researchers lack the required figures regarding the environmental impact of data centres. An educated guess? Streaming contents for an hour a day doubles your carbon footprint compared to not streaming at all.

“What we know, is that data centres are currently responsible for about one percent of the world’s energy consumption, and that smartphones are among the main drivers behind an increase in this share,” Walnum says.

The researcher is eager to see whether the continuous effort to make phones more energy efficient, can keep up with the ongoing streaming boom.

“The new 5G network will enable us to stream incredible volumes of data per second, probably amounting to 10 to 15 times more than today,” he adds.

Closing the loop

When your old mobile needs to be replaced, the ideal thing to do would be to hand it in at the electronics store. This way, you could allow some of the non-renewable substances to be retrieved. and the rest to be safely disposed of.

This part of the mobile’s life cycle, however, looks nothing like the closed loop it ought to be in a world of circular economics. Although Norwegians often hand in used phones, far too few do in the rest of the world.

There is another problem, too:

“Smartphones have become so complex that it is growing ever more challenging to retrieve, not to mention, recycle, their contents,” Walnum says. Consequently, recycling units tend to give priority to a couple of substances, leaving the rest to be thrown away – paradoxically whilst the world heads towards depletion of several minerals.

But then there is the black market in the developing world. In cities like Ghana’s capital city, Accra, unprotected from dangerous fumes, people are working on the remnants of iPhones and other disposed electronics, aiming to retrieve tiny parts and sell them on. Tragically, this recycling effort poses a great risk to both human beings, animals, and the environment.

Keep your phone a little longer

Whose responsibility is it, then, to deal with the giant environmental footprint of our dear companion - the smartphone?

“ The manufacturers, of course, should take action to ensure that social and environmental conditions meet international standards, also at their subcontractors. Our governments should work harder to close the loop that makes disposing of a mobile phone feel less like a criminal action," says Walnum.

But what can we, the consumers, do?

“As consumers, we should have better access to repair than we have now,” he says.

Controlling our own appetite for new products would also contribute positively. As your phone starts approaching the point where you think of replacing it, stop and think. Perhaps a new battery or a replaced screen could buy you some time?

“Our most important contribution as consumers is to keep our phones a little longer,” Walnum says.

References:

Hans Jakob Walnum & Anders S.G. Andrae: The internet: Explaining ICT service demand in light of cloud computing technologies. In Rethinking Climate and Energy Policies (pp. 227-241). Springer, Cham., 2016.

Louis-Philippe P.-V.P.Clément et.al.: Sources of variation in life cycle assessments of smartphones and tablet computers. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 2020. (Summary)

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

See more content from the Western Norway Research Institute:

-

Restrictions and climate change: Tourism in Svalbard will change in the coming years

-

1% of people cause half of global aviation emissions. Most people in fact never fly.

-

Researcher believes people should be allowed to travel abroad this summer

-

A Norwegian dilemma: Is it possible to get a second home in the mountains and maintain a clean, green conscience?