This article was produced and financed by the University of Bergen - read more

Storm tracks. The warm, moist conveyor belt that delivers storm after storm to us.

PODCAST: "It's not unreasonable to expect fewer storms, but the ones we get will be stronger, more intense," says professor Camille Li.

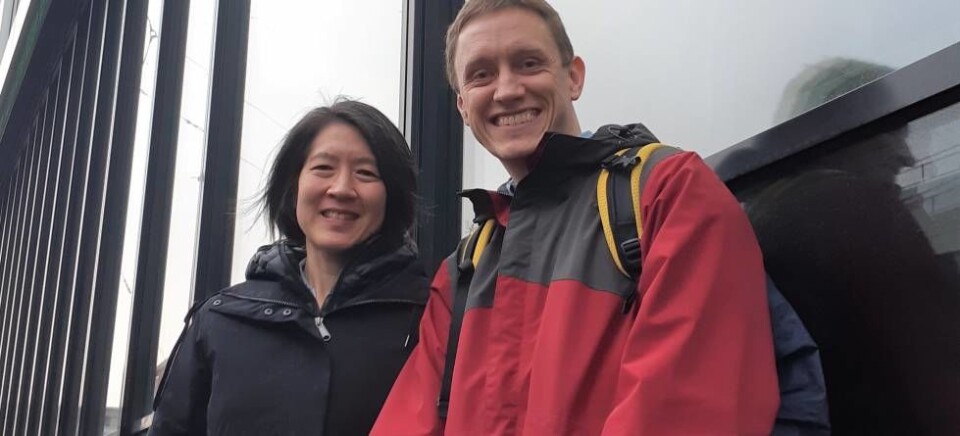

Professor Camille Li works on storm tracks, the warm, moist conveyor belt that deliver storm after storm to us here in Western Norway and the British isles.

Learn how these storm tracks work, how they will change as well as the research Camille Li and her colleagues are conducting at the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research:

"Storm tracks are corridors, where the storm systems like to travel. They are mainly over the oceans – there is one in the North Atlantic, one in the North Pacific – as well as in the southern hemisphere," says Li.

"We're at the tail end of the North Atlantic one here in Norway."

Many of these storms are located around the mid-latitudes, where we tend to find the largest contrasts between cold and warm – imagine the cold air of the poles meeting the warm air of the tropics – which works as the fuel for storms.

The other ingredient for kicking off storms are jet streams, strong air currents running around 10 kilometers above ground.

What about climate change?

The heat followed by a warmer climate means air can hold more moisture, which in turn should produce stronger storms. At the same time, the chancing climate is reducing the contrast between the warm and cold air, as the Arctic is warming faster than the rest of the globe.

"It's not unreasonable to expect fewer storms, but the ones we get will be stronger, more intense," says Li.

She has been working on the HAPPI simulations, in support of the IPCC 1.5 degree report last year. HAPPI used many different models, and ran many experiments on present climate, 1.5, and 2 degree warming to find differences between the two scenarios. Some areas – like the Mediterranean – saw larger changes.

"They are semi-arid, they really depend on their winter precipitation, most of their rainfall comes in winter. If they get one dry winter, or several in a row, it can have devastating impacts. The storm track there weakens over that half degree of warming."

In general the changes aren't that large from present day to 1.5 degrees in terms of storm tracks, but from 1.5 to 2 degrees the chances of dry decades become much higher.

"It's still a warmer, wetter world. Norway will get wetter, Bergen will get wetter, if you can believe that. What is normal rainfall today, would still be considered dry in a world with 2 degree warming."

On the other side of that, what is now considered a bad winter storm, would then be normal.

———