An article from University of Tromsø – The Arctic University of Norway

Spruce and pine survived the last ice age in Norway

Spruce and pine were able to survive the last Ice Age in Norway, and thus have a much longer history here than was previously thought. These conifers are much hardier than researchers believed, and will be able to tolerate climate change more than previous research suggested.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Botanists have long debated as to whether or not certain plants were able to survive the last Ice Age in Scandinavia, and so far it has been assumed that pine and spruce were not among the survivors.

Now, new research shows that these species may have existed in Norway as long as 22,000 years ago.

“Our research reveals that it is very likely that were trees in the northwest during and immediately after the last Ice Age,” says Ellen Elverland, a PhD candidate at the Tromsø Museum - University Museum, and one of many researchers who participated in the study.

“We’re definitely not talking about a forest here, but small stunted individuals that managed to survive unfavourable climatic periods. It’s possible that trees migrated to Scandinavia much earlier than we thought was possible.”

Better able to tolerate climate change

An understanding of the trees’ ability to disperse and their adaptability to climate is important to explain both the distribution of the individual species, and to help in predicting how ecosystems will respond to climate change.

“This is very relevant in light of current climate change, and will help us understand how can we adapt to global warming in terms of exploitation of natural resources and conservation of biological diversity,” says Elverland.

“If some individuals of these trees were able to survived the Ice Age in the north, that means that we have underestimated the ability of these species to survive at a minimal level and their rate of dispersal.”

Elverland points out that the discovery can have a significant economic impact on forestry, for example.

“The unique genetic resources that have been identified in spruce are important for the improvement of Norwegian spruce,” she explains.

Sediment samples from a pond

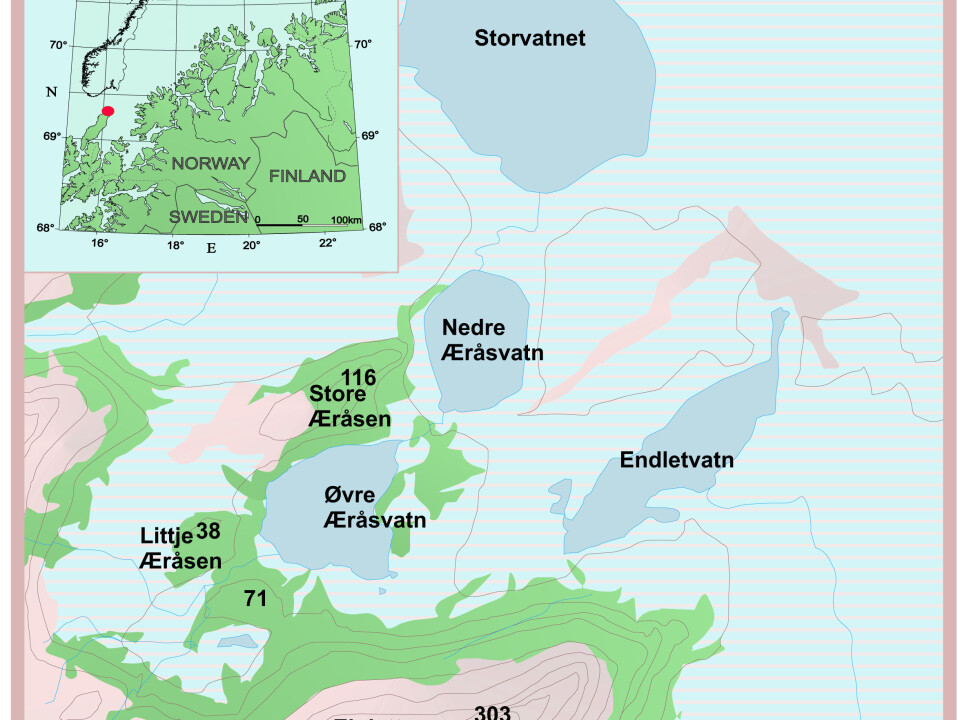

The findings are based on a three-part study in which researchers analyzed DNA from the existing spruce and fossil DNA in combination with more traditional studies of pollen and macrofossils from plants in sediment samples from a pond in Trøndelag and in Andøya in Nordland.

“The results show that much of the spruce in the north and west in Scandinavia has a unique genetic variant which means it must have wintered north of the ice sheet that covered northern Europe,” says Elverland.

“Furthermore, analysis of free fossil DNA in lake sediments showed traces of pine and fir in Andøya from 22 000 and 17 700 years ago.”

The prevailing view has been that pine migrated from the east about 9000 years ago, while spruce arrived about 2500-3000 years ago.

“Our findings therefore show that the trees were able to survive for thousands of years in a very harsh climate, and that they produced seed, spread and actually contributed to the genetic structure of spruce. This is a fascinating example of adaptation to climate change,” says the doctoral candidate.

Girl Power

Elverland’s participation in this startling research began with her work with plant remains found in bottom sediments from a lake in Andøya. Professor Inger Greve Alsos at the Tromsø Museum then put Elverland in contact with Professor Eske Willerslev and his PhD candidate Tina Jørgensen, who work with fossil DNA in Copenhagen.

“This contact with Willerslev enabled the cooperative effort to expand to include a Swedish-Norwegian research group of scientists, with Laura Parducci and Mari Mette Tollefsrud in the lead. They were also working with the same problem,” Elverland said.

“We decided that instead of competing, we should join forces and create a strong article that could be published in Science. Think of it as Girl Power instead of a cat fight,” she adds, laughing.

The research group, which has worked on the project since January 2010, has paid off. The group’s results were published in the 2 March print edition of the prestigious journal Science, a publication of the American Association for the Advancement of Science

“The research group was also recently awarded NOK six million from a research initiative to expand genetic studies of past vegetation.”