THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY THE University of Agder - read more

Historians have overlooked the role of Christianity

The role of Christianity in shaping the development of society has been given too little attention in Norwegian historical writing, according to professors.

“Norwegian historical writing has not adequately addressed the influence of Christianity on societal developments,” Helje Kringlebotn Sødal says.

She is a professor of the history of ideas and Christianity at the University of Agder (UiA).

This critique is supported by Knut Dørum, another history professor at UiA:

“Historians have overlooked the role of Christianity. The exploration of how faith has contributed to renewing Norwegian history and society has been too limited.”

Faith reduced to psychology

Dørum argues that Norwegian historians have relegated religious faith to mere psychology and viewed it as an external phenomenon devoid of intrinsic value.

“Christianity has been viewed as an ideological tool used by religious leaders for their power and interests. Historians have failed to understand that faith and salvation are driving forces on par with the pursuit of money and power,” Dørum says.

Book on the significance of Christian strategists

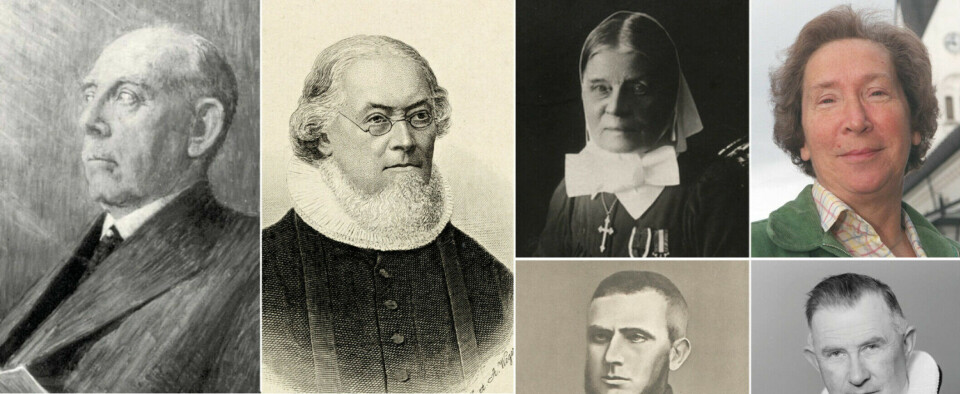

Sødal addresses this lack of Christian perspectives in Norwegian historical writing in the book Kristne strateger (Christian Strategists). Here, she and other researchers present 33 Christian strategists from Norway in the 1800s and 1900s. The first is the lay preacher Hans Nielsen Hauge, and the last is the first female bishop, Rosemarie Køhn.

The book includes chapters on lay preachers, hymnists, and novelists, as well as bishops and priests, and chapters on strategic theories and methods.

“Hauge and others like him helped to create a more diverse and democratic society. In practice, Hauge helped undermine absolute monarchy,” Sødal says.

Hauge was a farmer’s son, preacher, entrepreneur, and Christian strategist who lived from 1771-1824.

Sødal also underscores the significance of Hauge in empowering women to become active participants in the religious realm as preachers and leaders. Additionally, she reminds us that Hauge contributed to weakening the monopoly held by priests on preaching the word of God and the monopoly of city merchants on commerce.

“His primary motivation, however, was to awaken people from a complacent faith and inspire an active Christian life,” Sødal says.

Strategy in multiple areas

She wrote the chapter on Hauge together with Knut Dørum. They have also previously collaborated on a book about Hauge.

“Hans Nielsen Hauge was a pioneer. He inspired many of the other strategists we write about in the book and still continues to inspire,” Sødal says.

According to Sødal, the book sheds light on the role of Christianity in Norwegian history while also contributing to an understanding of strategic thinking and practice. Military and economic strategies are part of the theoretical backdrop for the book. The same goes for political strategy and leadership philosophy.

However, Sødal emphasises that the book’s main point is to reveal how Christian strategists think and act, as a strategic way of thinking and acting.

“A key point is precisely that faith serves as the driving force and guiding principle behind the plans the Christian strategists lay and the work they carry out,” she says.

Social welfare and prioritising others

“What is common to the Christian strategists is that they put others before themselves. Personal gain and success were not the goal, it was for others to be better off,” says Sødal.

However, she points out that they were not saints. Their motives may have been mixed.

“While traditional business strategy is concerned with making the strategy pay off, Christian strategists aim for it to benefit others first and foremost,” Sødal says.

International research on strategy calls this emphasis on users ‘other-regarding’. It is simply a matter of putting the target audience at the forefront when creating plans.

For the Christian strategists, this often led to dedication to social welfare and, not least, educational initiatives. Love of neighbour and their sense of duty to the Great Commission guided their strategies.

“This led to the creation of important social entrepreneurship. And it highlights the dual objectives of Christian strategists’ work. They sought not only to convert people to the Christian faith and lifestyle but also to combat poverty, alcohol abuse, injustice, and ignorance,” Sødal explains.

Started Norway’s first nursing programme

Sødal highlights nurse Kathinka Guldberg as an example of a Christian strategist with a dual purpose. Guldberg established Norway’s first nursing programme in 1886.

“Guldberg envisioned care for the sick and needy based on professional knowledge integrated with an understanding of patients’ spiritual needs. She is a prime example of a Christian strategist who aimed to evangelise while also enhancing people’s lives and health,” she says.

Society in a time of turmoil

Many of these Christian strategists lived in a time when Christianity was losing its support. The belief in science was starting to overshadow faith in God. This was what the strategists tried to counteract.

“The Christian strategists felt like they were in battle. They actively fought against secularisation, but also against poverty and abuse, selfishness and ignorance, and injustice and immorality. And they fought to spread a message of Christian charity in society and culture,” says Sødal.

Lost the battle against secularisation

The battle of the Christian strategists against secularisation may seem to have been lost in today’s society. However, Sødal asserts that they have left a lasting impact on Norwegian history in areas such as culture, education, politics, and many others.

Already in 1913, for example, Ole Hallesby helped establish Christian secondary school in the capital. And that is just one of the school establishments that has endured thanks to Hallesby.

Sødal also reminds us of Sigrid Undset (1882-1949). Undset is still actively read and studied all over the world today. Sødal has written a chapter on Undset in the book.

“Asbjørn Kloster is another noteworthy example. The restrictive alcohol policy in Norway in the 20th century is unimaginable without his efforts to aid people out of abuse and advocate for total abstinence during his lifetime, 1823-1876,” she says.

Kloster never managed to introduce a policy of total abstinence. But he helped many people overcome alcohol addiction. And according to Sødal, Norwegian alcohol policy is still influenced by his work.

This book is not the final word on the influence of Christianity on Norwegian culture and society, but Sødal believes it contributes to filling a gap in Norwegian historiography.

“This book can serve a starting point for readers and historians interested in delving deeper into this neglected area of Norwegian history,” Sødal says.

This content is paid for and presented by the University of Agder

This content is created by the University of Agder's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Agder is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

More content from the University of Agder:

-

Fear being rejected: Half pay for gender-affirming surgery themselves

-

Study: "Young people take Paracetamol and Ibuprofen for anxiety, depression, and physical pain"

-

Research paved the way for better maths courses for multicultural student teachers

-

The law protects the students. What about the teachers?

-

This researcher has helped more economics students pass their maths exams

-

There are many cases of fathers and sons both reaching elite level in football. Why is that?