An article from University of Oslo

Children and the Internet is an ethical minefield

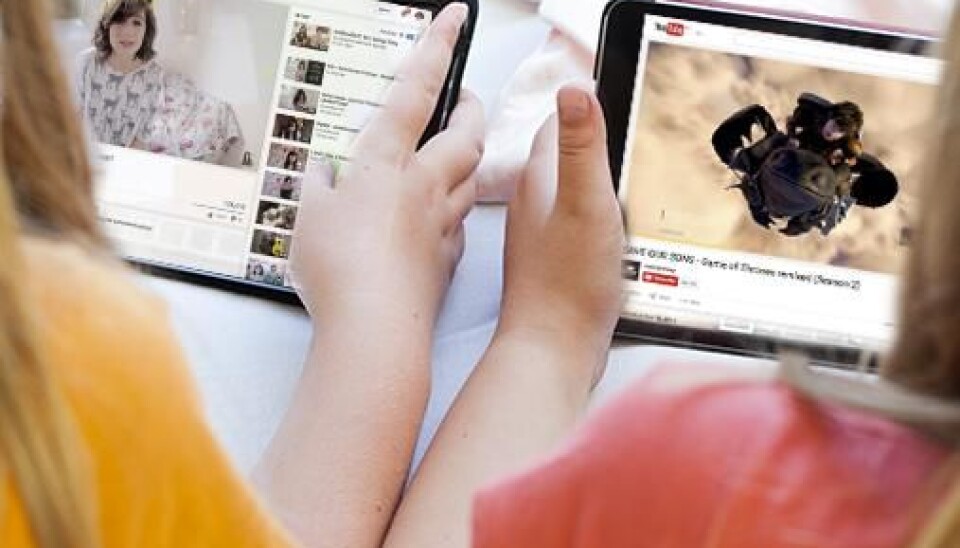

When children are asked about their Internet use, their responses differ to those of their parents. This is one of many ethical dilemmas for those conducting research with children. The children’s answers often challenge adults' view of children.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Researchers have traditionally asked parents about issues affecting children. When it comes to children's media use, there’s no point in relying on information from parents alone, according to media researcher Elisabeth Staksrud. She has extensive experience from the project EU Kids Online and has led several international quantitative studies of children and risk behaviour on the Internet.

“We have to ask the primary informants; the children. If we do not address the difficult questions directly to the children, our research will be flawed”, she says, and refers to a survey conducted in 2002 and 2003, when questions were posed to both the children and the parents for the first time.

“We got completely different answers. Among other things, almost 83 per cent of the parents said that they always or almost always sat with their children when they were online. Only 23 per cent of the children said the same. Research on children's Internet use highlights children's rights. Children not only have the right to protection, but also the right to participate”, says Staksrud.

“In order to ensure that the children's voices and experiences form part of the research, we are conducting research with children; not on children. This means for example that we regard children to be competent to answer questions that concern them.”

Experience shows that children and young people can fill out complex questionnaires, covering areas such as risk behaviour online. However, this research also faces a wide range of ethical challenges.

“This is an ethical minefield. We must tread very carefully. The fact that children’s answers are often completely different to their parents' is one of many dilemmas”, cautions Staksrud.

The duty to report harmful conditions

Good research practice dictates that informed consent is obtained from both the children and the parents, and this is also sometimes a statutory requirement. The children must also be able to respond to questionnaires under the promise of anonymity, when necessary. Sometimes this also applies to the children’s anonymity in relation to parents or teachers.

“What sometimes happens is that parents who have initially given their consent subsequently want to retract it in order to see how their children have responded”, says Staksrud.

“We will not do this if we have promised a child complete anonymity. It is therefore important to explain well in advance what we are doing and why, so that both the parents and the children understand what they are agreeing to, and why it is important that the children can also be anonymous.

However, anonymity is not boundless.

“We have a duty to report the matter if the children tell us about harmful situations, such as being subjected to violence or sexual abuse, or that others are in imminent danger of harm. We have to establish established mechanisms to deal with this possibility before we start our data collection.”

“Can we believe what children say or how they respond in a survey?”

“Yes. The quality of their responses is not inferior to those of their parents; on the contrary. We have seen that the children are normally more honest and truthful, but we are totally dependent on them feeling that they can trust us”, explains Staksrud.

Many myths surrounding digital bullying

Risk behaviour online is not just about children being exposed to pornography and paedophiles. Commercial pressures and digital bullying are also a problem.

“Our studies show that it is digital bullying that often causes the most harm. However, many parents have no idea about the digital bullying their own children may face. Parents cannot therefore be used as the authoritative source of information when it comes to cyberbullying”, says Staksrud. She has written a book about digital bullying, which affects a large number of Norwegian children.

“There are many preconceptions surrounding this issue. One of them is the image of the bully as the strong one, the one with the power. However, our research shows that the digital bully has strong vulnerability traits and often struggles with other self-destructive behaviour. We therefore need to think differently about this issue.”

Children know more than we think

Media researchers are also concerned with the dilemma of a negative learning effect. When children are asked whether they have seen pornography or read on a website how to make bombs, this may be introducing them to something new and harmful which they had previously been unaware of.

“In our case, we were particularly aware of the dilemma we like to call harmful user-generated content, i.e. websites that for example explain how to commit suicide, or that are racist or promote anorexia”, says Staksrud.

In the extensive EU Kids Online survey, such questions were therefore only posed to children from 11 years and over.

“What we often see, nevertheless, is that children are already familiar with these types of websites, even although we are not aware of it. In many ways, we project our own ideas and prejudices.”

“Do children's answers challenge our view of them?"

"Yes, that’s exactly right. And what has surprised me the most when researching children's Internet use is how many people do not believe our findings. The argument ‘but children probably lie on questionnaires’ is something I hear often, because adults struggle to acknowledge the darker experiences children are exposed to. This applies not only to parents, but also politicians, bureaucrats and other decision-makers.”