This article was produced and financed by University of Stavanger

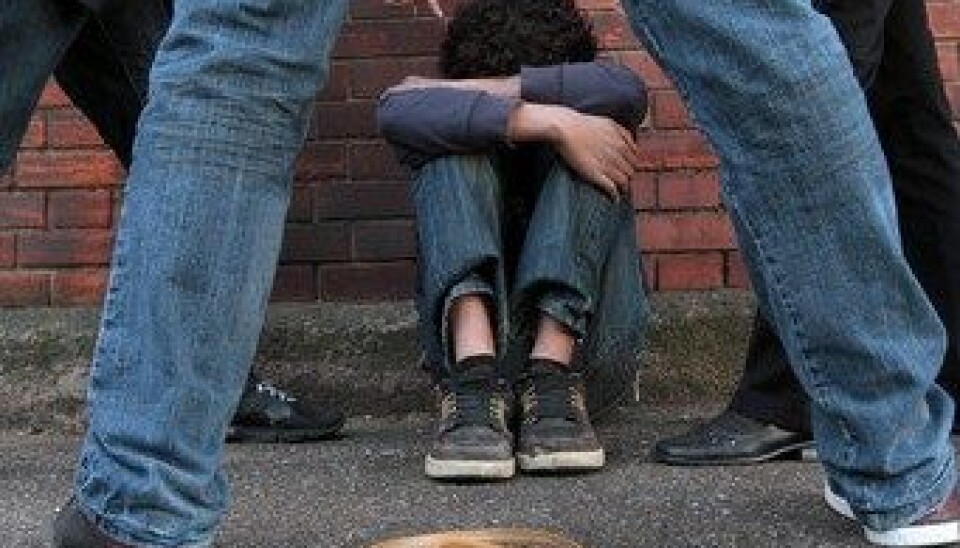

Being bullied can cause trauma symptoms

Problems caused by bullying do not necessarily cease when the abuse stops. Recent research shows that victims may need long-term support.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

This study of 963 children aged 14 and 15 in Norwegian schools found a high incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms among bullied pupils. These signs were seen in roughly 33 per cent of respondents who said they had been victims of bullying.

“This is noteworthy, but nevertheless unsurprising,” says psychologist Thormod Idsøe from the Universitiy of Stavanger (UiS) and Bergen’s Center for Crisis Psychology. “Bullying is defined as long-term physical or mental violence by an individual or group.

”It’s directed at a person who’s not able to defend themselves at the relevant time. We know that such experiences can leave a mark on the victim.”

He has published an article on “Bullying and PTSD symptoms” in the Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology with colleague Ella Maria Cosmovici Idsøe at the UiS Centre for Behavioural Research and psychologist Atle Dyregrov from the Center for Crisis Psychology.

The study measured the extent of intrusive memories and avoidance behaviour among pupils. These are two of three defined PTSD symptoms. The third, physiological stress activation, was not covered.

High levels of defining signs

Recent research on working life has found that 40-60 per cent of adult victims of bullying reveal high levels of these three defining signs.

But few national or international investigations have been conducted on the relationship between being bullied and PTSD symptoms among schoolchildren.

“Traumatic experiences or strains imposed on us by others can often hurt more than accidents,” says Idsøe. “That could be why so many pupils report such symptoms.”

They can cause great difficulties concentrating, have a disruptive effect and prevent sufferers from functioning normally in daily life. Idsøe has personally seen how PTSD symptoms can create problems for schoolchildren.

“Pupils who’re constantly plagued by thoughts about or images of painful experiences, and who use much energy to suppress them, will clearly have less capacity to concentrate on schoolwork. Nor is this usually easy to observe – they often suffer in silence.”

More girls

The research also shows that girls are more likely to display PTSD symptoms than boys, Idsøe reports. “That accords with studies of other types of strain.

“We also found that those with the worst symptoms were a small group of pupils who, in addition to being victims of bullying, frequently bullied fellow pupils themselves.”

He finds it difficult to provide a definite explanation of why some groups are more likely to develop PTSD symptoms, but says this question is a general issue among trauma specialists.

“One explanation, for example, could be that difficult earlier experiences make the sufferers more vulnerable, and they thereby develop symptoms and mental health problems more easily.”

Awareness

He hopes that the study’s findings can help to boost awareness that a number of bullied schoolchildren may need support even after the mistreatment has ended.

“In such circumstances, adult responsibility isn’t confined to stopping the bullying. It also extends to following up the victims.”

Idsøe and his co-researchers have not investigated how much help bullied pupils get afterwards, but their impression is that such follow-up remains inadequate.

Immediate

“We know that Norwegian schools devote much attention to putting a stop to bullying it, and that pupils who need immediate support do receive it,” Idsøe says.

“But we also see that such assistance stops too early. Although the bullying may have ended, PTSD symptoms could persist for a long time with some children.”

In his view, teachers and schools should be aware of the need certain pupils might have for long-term follow-up. In some cases, that could also require the involvement of the health service.

“It’s important to monitor how pupils develop after being bullied, and to be aware of the possibility that they might develop PTSD symptoms.

“It’s not always easy to spot that a child is being plagued by intrusive memories and avoidance strategies. So teachers must be offered more information on these conditions.

“They need to know how to detect that a pupil needs to be referred on, and must be able to tailor teaching for children with such difficulties.”

Limitations

Idsøe acknowledges that the study has its methodological limitations, and that more detailed studies of the link between bullying and PTSD are therefore required.

“Although we asked about PTSD symptoms related to episodes of bullying, we can’t exclude the possibility that the responses may relate in some cases to other traumatic incidents,” he says.

To study this in more detail, the researchers will now join a Finnish study of 1 100 schoolchildren to check the relationship between bullying and PTSD symptoms regularly over several years.

Idsøe also belongs to a national research group investigating the link between being bullied and the psychiatric diagnosis of PTSD. That involves more criteria than a high level of symptoms.

-----------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Rolf E. Gooderham