This article is produced and financed by The Centre for Advanced Study (CAS) - read more

Why do Indigenous people have high risk of severe influenza?

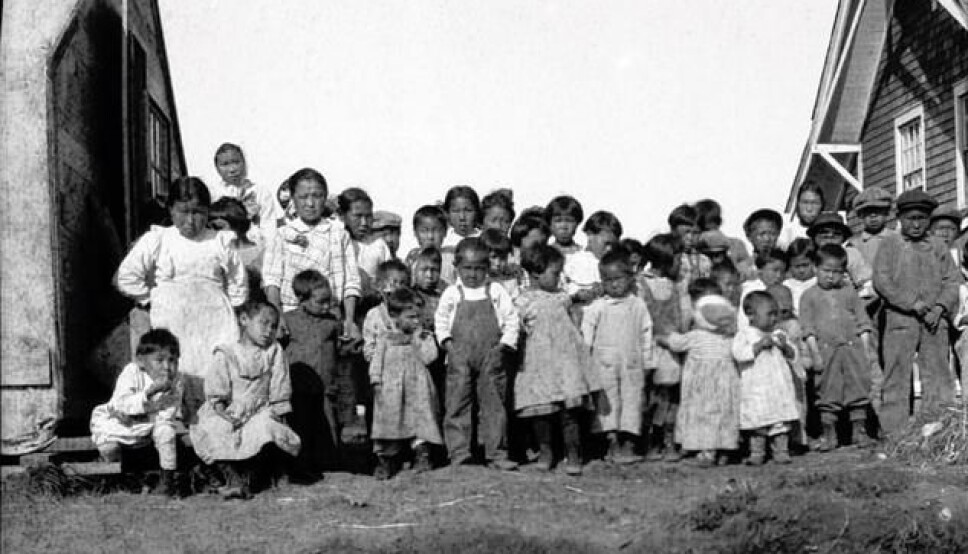

The influenza pandemics of 1918 and 2009, as well as the ongoing COVID-19, show that Indigenous people have extremely high risk of severe disease outcomes, but the reasons for this vulnerability are unclear.

Between 290,000 and 650,000 people die from influenza annually.

However, these deaths are not evenly spread among ethnic groups, says Research Professor at Oslo Metropolitan University (OsloMet) Svenn-Erik Mamelund.

Mamelund is a pandemic researcher interested in influenza, a vaccine-preventable disease that nonetheless remains one of the world’s greatest public health challenges.

“Akin to medical risk groups such as certain age groups, pregnant women and the previously ill, Indigenous populations in North America and Oceania are uniquely at risk for severe disease and death, both today and 100 years ago”, says Mamelund.

Why is that so?

Mamelund aims to try and answer this question during his year at CAS, in 2022/23.

Heightened death rate

For 25 years, Svenn-Erik Mamelund has been researching influenza pandemics, in particular the Spanish flu, which raged in 1918-1920 and killed between 50 and 100 million people globally.

The death rates amongst isolated Indigenous peoples in Scandinavia, North America and Oceania were between three and eight times higher than among the white majority populations living in the corresponding, less isolated areas.

“In West Samoa, 24 per cent of the Indigenous people died from the disease. In Enare in Finnish Sapmi, the death rate was 10 per cent”, Mamelund says.

The average death rate in Alaska was 8 per cent, but on the Seward Peninsula on the western coast of the state, home to different native communities, it reached a horrific 90 per cent in the village of Brevig. The 72 victims were buried in a mass grave in the permafrost. The survivors were eight children, most of whom ended up in orphanages when their parents died.

Hard hit once again by COVID-19

“Indigenous people are once again hard hit during a pandemic, at least as reported by the media”, says the professor, referring to the ongoing COVID-19 crisis.

One recent study from New Zealand shows that COVID-19 infection fatality rates are at least 50 per cent higher for Māori and Pacific people than for New Zealanders with European backgrounds.

“Suggested explanations were poorer baseline health and lower life expectancy, crowded housing, being more likely to work in occupations with higher exposure, and unmet health needs”, says Mamelund.

“The influenza pandemics of 1918 and 2009, as well as the ongoing COVID-19, show that Indigenous people have extremely high risk of severe disease outcomes, but reasons for this vulnerability are unclear.”

Prior research has studied continents separately, or focused exclusively on genetic, social or historical risk factors. Mamelund and his team seek to see the whole picture.

“Our project will for the first time explore biological, social and historical factors for why Indigenous peoples are associated with a higher risk of tragic pandemic outcomes across three continents”, he says.

Ambitions of excellence

At the Centre for Advanced Study CAS, a research centre based in Oslo, Norway, researchers get one year with uninterrupted time for research.

Mamelund is ambitious with clear goals for his year at the centre. Having previously been a fellow, he saw how important the year at CAS was for his project leaders in creating future research tracks and network, doing outreach activities and cooperations.

‘My ultimate goal is to build a Centre of Excellence in transdisciplinary studies of emerging pandemics at OsloMet”, the professor states.

“I hope that a year at CAS - to do curiosity-driven research with colleagues which is often hard to do from a distance - can help consolidate my research ambitions.”