This article was produced and financed by NILU - Norwegian Institute for Air Research

Volcanic ash data saves European air traffic

After a volcanic eruption in Iceland in May 2011, the Met Office in London warned that volcanic ash could represent a danger to air traffic in southern Norway. But Norwegian experts had their own satellite data and concluded that air traffic could resume as normal.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

When Iceland’s Eyjafjallajökull volcano erupted in April and May 2010 , it hurled vast quantities of ash into the atmosphere. Norwegian and international aviation authorities were poorly prepared.

The ash cloud grounded more planes than any previous volcanic eruption, and millions of airline passengers were stuck in airports. Consequently, airlines lost huge amounts of money.

But when Iceland’s Grimsvötn volcano in Iceland erupted a year later, on 21 May 2011, both Norwegian and international aviation authorities were far better prepared.

A couple of days after the volcano erupted, the London Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre (VAAC) warned Norway about too high concetrations of ash above Haugesund, Stavanger and Kristiansand. They claimed it was so high that it would be inadvisable to fly, making thousands of passengers stranded in airports.

An emergency meeting

In spite of Brithish warnings, Norwegian air traffic was able to continue as normal because the country’s aviation authorities had entered into a unique collaboration with a number of Norwegian research institutions.

Experience from the Eyjafjallajökull eruption led to the establishment of the Agency Volcanic Ash Group (EVA), with representatives and experts from the Civil Aviation Authority, Avinor, the Norwegian Meteorological Institute and the Norwegian Institute for Air Research (NILU).

When the Grimsvötn volcano erupted, EVA members were called into an emergency meeting, where scientists were able to present reliable satellite data on the probability of high concentrations of ash in airspace over the southwestern part of Norway.

This was a historic decision: Norway was the first country in Europe that chose to rely on national expertise instead of warnings from the VAAC.

This decision helped airlines save money and prevented a great number of travellers suffer the inconvenience of being unnecessarily grounded.

The good news were sent to airlines just minutes before air traffic over large parts of southern Norway were paralyzed, and EVA subsequently carried out daily meetings until the volcano’s eruptions calmed down. It turned out that the Norwegian forecasts were accurate.

Norwegian airlines thus avoided significant economic losses from rescheduling several hundred flights, while air traffic over Iceland, northern Sweden, Denmark, Germany and Scotland was hit hard.

Satellite data kept the air space open

“It was primarily observational data from satellites that enabled us to make good enough estimates of the ash concentrations from the eruption. EVA is a concrete example of how a good relationship between research community and regulatory agencies can provide results that benefit society,” says Kjetil Tørseth, director of NILU’s Department of Atmospheric and Climate Research.

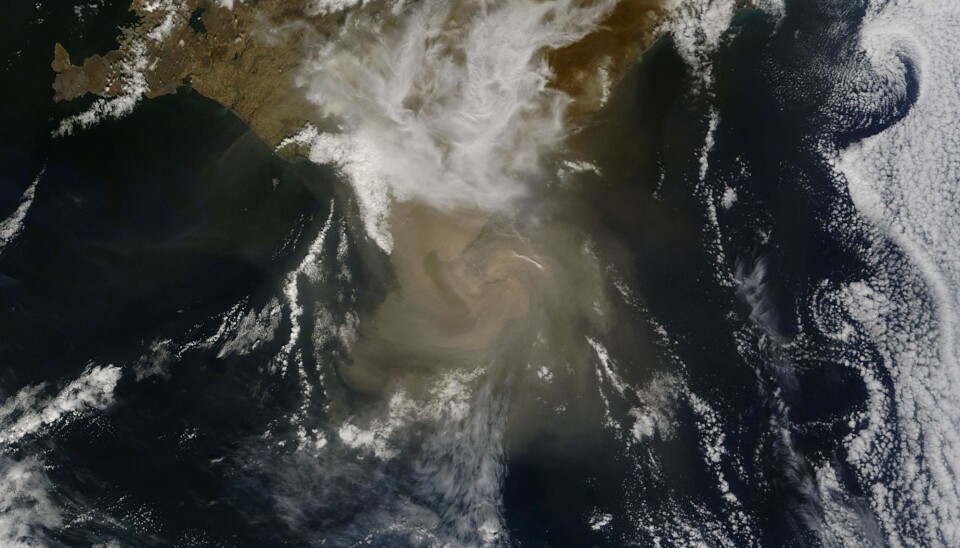

NILU has studied the spread and detection of volcanic ash clouds for a number of years, and has monitored the spread of ash clouds using satellite-borne instruments that were originally designed to detect radiation and clouds.

“Researchers at NILU have developed methods that make it possible to use data from these instruments to determine whether there is ash in the atmosphere. These algorithms proved their worth when the Grimsvötn volcano erupted in May 2011,” says Tørseth.

The Eyjafjallajökull eruption in 2010 led to several changes in international aviation authority regulations.

“When Eyjafjallajökull erupted, regulations were issued that prohibited commercial flights if there was any ash whatsoever in the air. But this was too restrictive, so threshold levels were established that would allow planes to fly in low levels of ash if certain procedures were followed. In May 2011, the VAAC in London forecasted that these threshold limits should be exceeded in southern Norway, while our satellite data showed lower ash concentrations than the limits,” he says.

Although the Norwegian government chose to ignore the VAAC advice to close air space, it does not mean that the watchdogs in London did a bad job. Providing forecasts of ash concentrations is actually a very difficult task.

“Using national, as well as international expertise, provided an improved basis for decision-making. In addition, this made it possible to take advantage of local knowledge and made for closer proximity to the important decisions that had to be taken,” says the researcher.