THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology - read more

A new invention could revolutionise the development of self-driving cars

It makes GPS more precise, so you always know exactly where you are.

We mostly take it for granted that the position shown by our GPS is correct.

But if we are in a new city and use the map app on our phone to find our way back to the hotel, it can often look like we're jumping around from one point to another as we walk. Even though we're actually walking quite normally on the same pavement the whole time.

“Cities are brutal for satellite navigation,” says Ardeshir Mohamadi.

He is a doctoral student at NTNU, researching how to make affordable GPS receivers – like the one in your phone or your fitness watch – much more accurate, without having to use costly additional services.

Having an accurate GPS position is especially important for cars that are designed to operate without a driver, so-called autonomous or self-driving vehicles.

Urban canyons

Mohamadi and his colleagues at NTNU have now developed a new system to help autonomous vehicles navigate safely within cities.

“In cities, glass and concrete make satellite signals bounce back and forth. Tall buildings block the view, and what works perfectly on an open motorway is not so good when you enter a built-up area,” says Mohamadi.

The problem is that signals are reflected between buildings and take longer to reach the receiver. As a result, the calculation of the distance to the satellites is incorrect, and the position becomes inaccurate.

These types of difficult city environments are often called ‘urban canyons.’ It's as if you're at the bottom of a deep ravine.

The GPS signals that do reach you, or the self-driving car, may have been reflected many times on their way down into the ravine.

Prevents hesitant, unreliable driving

“For autonomous vehicles, this makes the difference between confident, safe behaviour and hesitant, unreliable driving. That's why we developed SmartNav, a type of positioning technology designed for urban canyons,” says Mohamadi.

It’s not just that the satellite signals are disrupted down there among the tall buildings. Even the signals that are correct still lack sufficient precision.

To solve this problem, the researchers combined several different technologies to correct the signal.

The result is a computer program that can be integrated into the navigation system of autonomous cars.

To achieve this, they also received help from a new Google service.

Can radio waves be used?

It is this code that often becomes incorrect when the signal bounces around between buildings in a city.

The first solution the researchers studied was therefore to drop the code altogether. Instead, they use information from the radio wave itself.

Is the wave travelling upwards or downwards when it reaches the receiver? This is called the carrier phase of the wave.

“Using only the carrier phase can provide very high accuracy, but it takes time, which is not very practical when the receiver is moving,” says Mohamadi.

The problem is that you have to stay still until the calculation is good enough – not just a microsecond, but for several minutes.

The researchers tested several methods

But there are other ways to improve a GPS signal. The user can use a service that corrects the signal using base stations called Real Time Kinetics (RTK).

RTK works fine as long as the user is close to one of these stations. But this is an expensive solution, intended for professional users.

An alternative approach is PPP-RTK, which combines precise corrections with satellite signals. The European Galileo system now supports this by broadcasting its corrections for free.

But there is even more help available.

Google and the wrong-side-of-the-street problem

While the NTNU researchers were working on finding better solutions, Google launched a new service for its Android users.

Imagine you're planning a holiday to London. You open Google Maps on your tablet. You then enter the address of your hotel, and you can immediately zoom in on the street environment, study the hotel’s façade, and see the height of the surrounding buildings.

Google now has such 3D models of buildings in almost 4,000 cities around the world.

The company uses these models to predict how satellite signals will be reflected between buildings.

This is how they will solve the problem of it appearing as though you're walking on the wrong side of the road when using the map app to, for example, find your way back to the hotel.

“They combine data from sensors, Wi-Fi, mobile networks, and 3D building models to produce smooth position estimates that can withstand errors caused by reflections,” explains Mohamadi.

Precision you can rely on

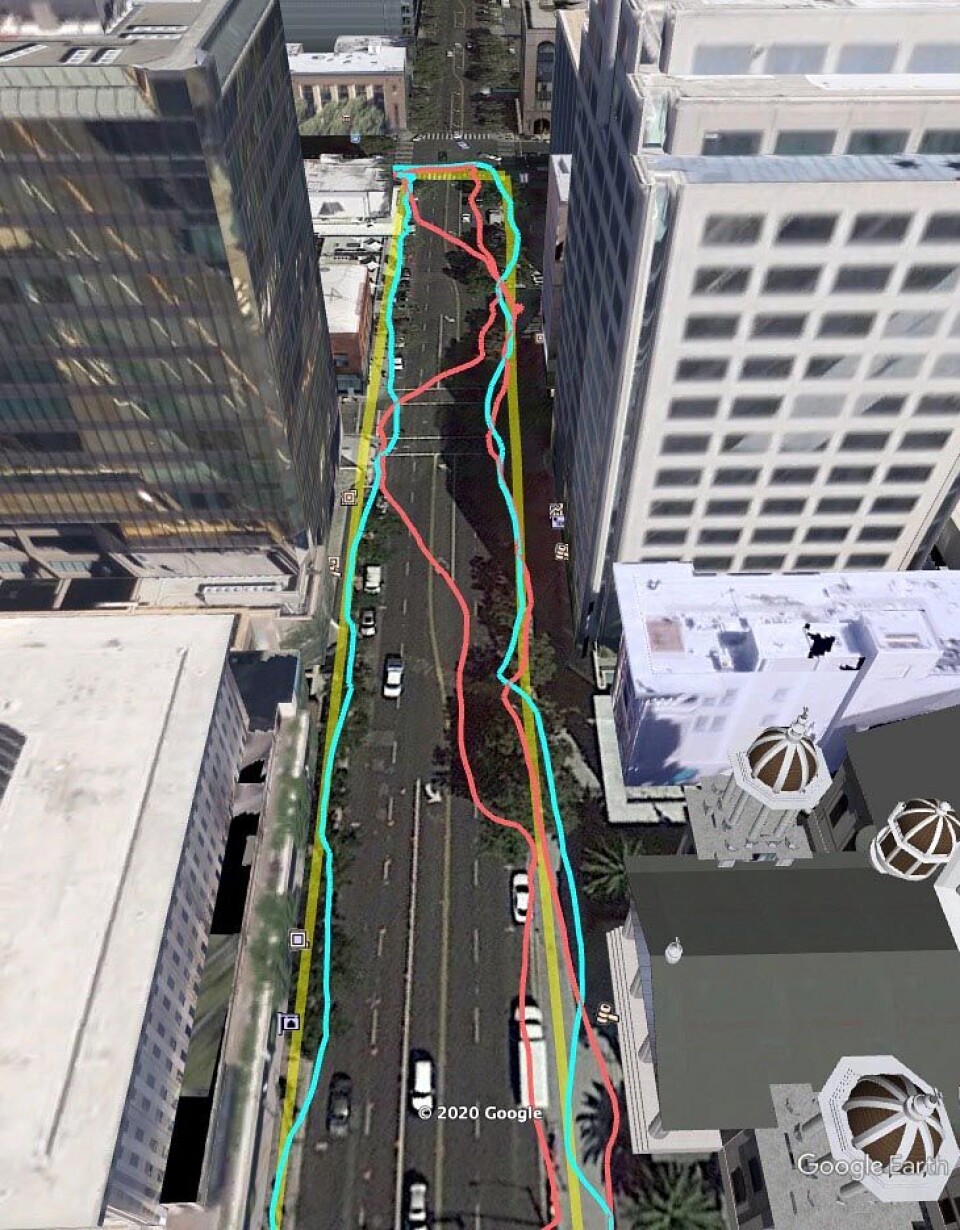

The researchers were now able to combine all these different correction systems with their own algorithms. When they tested it in the streets of Trondheim, they achieved an accuracy better than 10 centimetres 90 per cent of the time.

According to the researchers, this provides precision that can be relied upon in cities.

The use of PPP-RTK will also make the technology accessible to the general public because it's a relatively affordable service.

“PPP-RTK reduces the need for dense networks of local base stations and expensive subscriptions, enabling cheap, large-scale implementation on mass-market receivers,” says Mohamadi.

References:

Mohamadi et al. Phase-Only positioning in urban environments: assessing its potential for mass-market GNSS receivers, Journal of Spatial Science, vol. 70, 2025. DOI: 10.1080/14498596.2025.2536567

Coming soon: FLP-Aided GNSS RTK Positioning: A Means of Supporting Smartphone High-Precision Positioning in Dynamic Urban Environments, Journal of the Institute of Navigation.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

More content from NTNU:

-

Perpetrators of violence may benefit from prompt help

-

The Nazis had "crazy" theories about the origins of the Sámi

-

This medication is good for mum, but her kids have a higher risk of developing allergies

-

Here's the first Viking high seat crafted in central Norway in 1,000 years

-

Researchers are now able to detect aggressive prostate cancer

-

Can desert sand be used to build houses and roads?