An article from Norwegian SciTech News at NTNU

Family’s hereditary cancer gene found

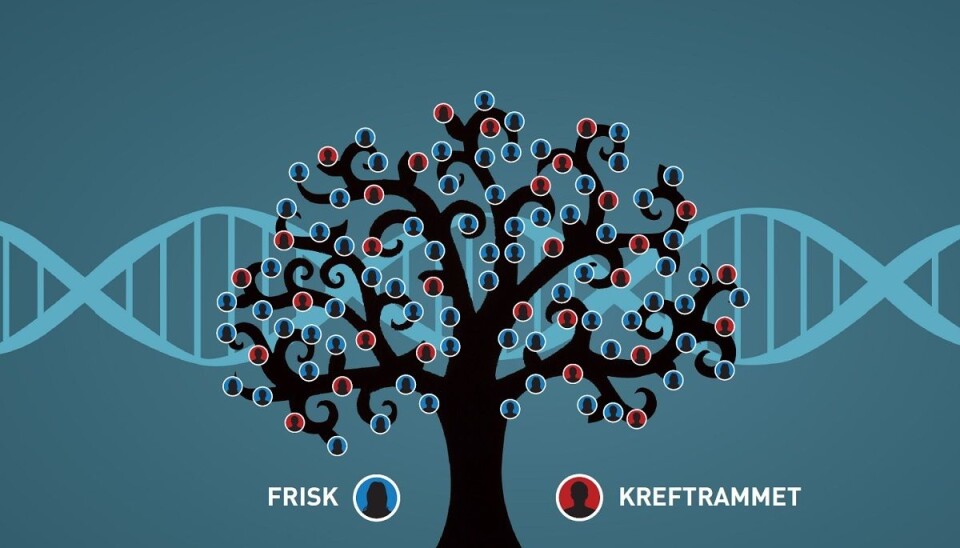

When almost a third of a hundred members of one family had cancer, or were cured of cancer, researchers began to look for a cancer-causing gene in the family. They found it after fifteen years of genetic testing.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

The breakthrough means that families who have inherited this cancer-predisposing gene mutation can get better help. Starting next year, the new method of genotyping will be offered at St. Olavs Hospital in Trondheim.

This is the first time a family has been tested at NTNU and St. Olav’s Hospital using this method.

Typically, many people from families with inherited cancer risk avoid annual screening tests even when a hospital offers genotyping.

Many avoid cancer screening

For 15 years, this particular family had been tested using an old genotyping method, where one gene at a time was examined.

The researchers didn’t find anything, and the results were discouraging. But when the researchers used the new high-capacity DNA sequencing method, they found the gene mutation that created cancer in this particular family after only a few weeks

This method allowed researchers to search through 22 000 genes.

In families with a high hereditary cancer risk, all family members need to get regular screening tests since there hasn’t been any reliable way to find a specific cancer-causing gene up to now. These screenings are costly. In the family being studied, many individuals have colon cancer, and a colonoscopy is the screening method used to illuminate the intestine. Many people find this examination uncomfortable, and in some cases it can cause damage to the intestine.

A blueprint for what we have inherited

Unpleasant screening methods are challenging enough, but being a member of a family with a lot of cancer and not knowing whether one has inherited the gene mutation that causes disease can also be very stressful.

Individuals who have inherited the specific gene mutation often come down with the disease sooner or later. If you don’t inherit the mutation, you don’t get the disease and you avoid all the screenings and uncertainty.

The Human Genome Project has made this next-generation genetic testing possible. An international research group spent 13 years on mapping and understanding all the genes in humans. In 2003 they reached their goal. This paved the way for scientists to develop the technology that has made it possible to test all of a person’s genes since 2005.

Method in use for a while

“This method has been used in research since 2005, but it takes time until a new approach has been tested and proven enough to be used diagnostically in a clinical hospital environment. Now most gene laboratories are transitioning to this method, says Maren F. Hansen, a PhD research fellow in the Department of Laboratory Medicine, Children and Women’s Health at NTNU.

She and the research group that she is a part of tested the new method on the high cancer-risk family where almost a third have or have had cancer.

“We were confident that there was a mutation in a gene that made so many of them sick,” says Hansen. A mutation is defined as a change in the genetic material. This often leads to disease.

Gene mutation made many sick

To map the entire family, researchers thoroughly investigated the family’s history. They tracked down church records and other genealogical sources until the entire family tree was clear.

Fourteen family members, including both sick and healthy individuals, agreed to be tested. After applying the new method, Hansen came away with 60,000 different DNA variants in 14,500 genes. The first filtering was to see which gene mutations the sick individuals had in common that healthy family members did not have.

The result? Hansen was left with a single gene mutation that all the sick individuals had. The mutation was in a gene that copies DNA during cell division.

“This gene normally includes an auto-correct function, like when you type something, and if it’s wrong, then the auto-correct mode corrects the mistake. But the sick family members had an error in this automatic correction. Their gene didn’t correct the DNA mistakes, and this caused mutations in a lot of other genes. That’s what made them sick,” says Hansen.

Six of fourteen had inherited cancer gene

Of the fourteen family members who were tested, six of them carried this mutation. Their children will have a 50 per cent risk of inheriting the mutation. After the first round, six more people were tested. All six were sick and had the mutation.

“We also tested 95 people who had no connection to the first family,” Hansen said. “We found a person who was suffering from cancer and who had exactly the same gene mutation as the family we tested. We didn’t know that he was related to the others we’d tested, but some genealogical research revealed that he actually was. When we examined more members of this man’s family, we also found the same mutation in his brother and son, who were both sick.”