THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY THE University of Agder - read more

Children's literature is more complex than we realise

Five of the seven texts examined by Berit Huntebrinker have the clear purpose to teach young people to respect nature.

“The authors I studied agree that a change is needed in the ways we behave towards nature, but they do not agree on what those behaviours should be,” Berit Huntebrinker says.

She is a researcher at the University of Agder (UiA).

Huntebrinker has examined four picture books for children and three comics. All are written and illustrated by Norwegian authors and illustrators. The texts were published from 1974 to 2019.

How is nature portrayed?

A central question for the researcher was whether nature has intrinsic value or if it is just something to be used for our own ends.

“I examined how the characters in various texts look at nature, and what thoughts and ideals about nature are represented in text and images,” Huntebrinker says.

Her reading is based on what comparative literature calls an ecocritical perspective. In short, it means to see how literature portrays our relationship with nature.

“The texts selected emphasise, in different ways, that we have a moral duty to use less, recycle more and take better care of nature,” she says.

Trying to educate the reader

Five of the seven texts have the clear purpose to teach young people to respect nature.

“Some of the texts are directly educational. They are quite moralising. Others are more open and inviting. They leave it up to the reader and the characters in the book to judge the content for themselves,” Huntebrinker says.

She singles out the octopus Blekkulf as an example of a moralising text:

“The character Blekkulf is designed to teach young people how to protect the environment. Educating the reader is the primary goal. And there is little doubt about what the right and wrong actions are,” the researcher says.

Environmental citizenship

The national curriculum emphasises that three themes must be included in the teaching of all subjects in Norwegian primary and lower secondary schools: sustainable development, democratic citizenship, as well as public health and life skills.

An important part of the thesis deals with citizenship. Huntebrinker looks at how the main characters in the texts are presented as citizens who are responsible towards nature.

The majority of the texts are characterised by the individual having responsibility for nature, but being free to choose what measures they want to use. She calls this, in accordance with political science theory, a liberal type of citizen.

“It doesn't surprise me. Children's books and popular literature are often simplified presentations, and the individual is often the focus in popular literature,” she says.

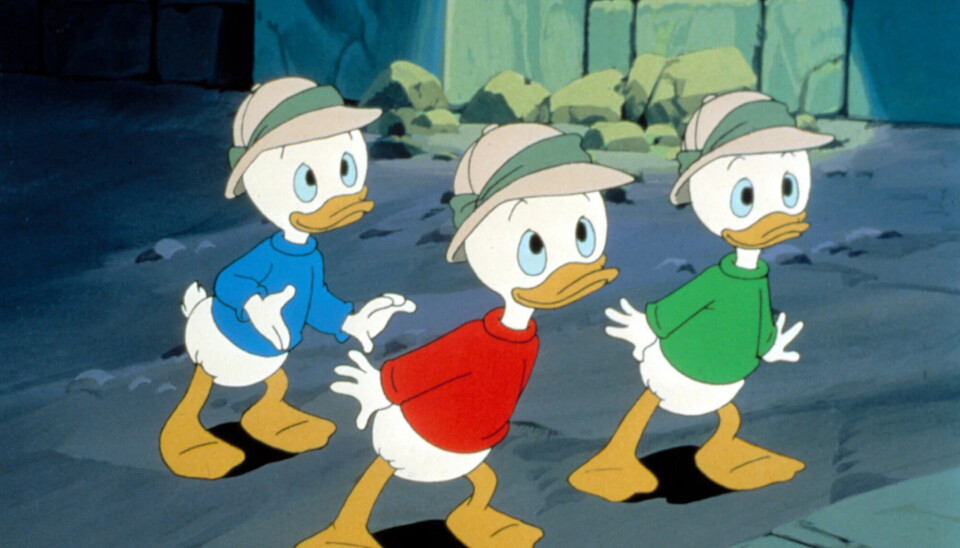

She mentions the Donald Duck comic book as an example of a story where the heroes are given personal responsibility for cleaning up environmental problems.

“In an individualistic perspective like this, there is less room for political responsibility for changing society. Collective responsibility and overall social organisation fall out of sight,” says the researcher.

Individual and collective responsibility

She highlights Det blå folket og karamellfabrikken (The blue people and the caramel factory) (1974) as one of the most artistically interesting books in the study. The book is written by Tor Åge Bringsværd and illustrated by Thore Hansen.

The blue people in Bringsværd’s book wake up a sleeping town to make the inhabitants aware of the serious air pollution from the local caramel factory.

Bringsværd, too, stresses individual responsibility and the freedom to choose how you want to protect nature. But he also emphasises the collective responsibility.

The researcher calls the latter a republican citizen, still using concepts from political science. For such a citizen, society's common laws and rules count for a lot.

“With Bringsværd, the group - the blue people - works together to protect nature. The author and his main characters are deeply aware of the challenges we face from pollution. At the same time, they are radically critical of the social and political conditions of Norway in 1974. The book highlights both the lack of individual responsibility and the societal conditions,” Huntebrinker says.

'Fable prose'

“The townspeople have to decide whether they want to close the factory or continue making caramels,” Huntebrinker says.

She reminds us that Bringsværd calls his work ‘fable prose’, a term that he coined.

“Fable prose means that the story comes in disguise so to speak, as a reflection of something else, to tell us something about our lives. By using fantastic elements and strange events, the author helps us see our own lives in a new perspective,” she says.

She encourages a nuanced and critical reading also of children's books and popular literature.

“A nuanced reading is fruitful and necessary to fully appreciate the complexity of children's literature, also when it comes to the presentation of different views about our responsibility for nature,” Huntebrinker says.

Reference:

Berit Martha Christel Huntebrinker: Narrating Environmental Citizenship. Norwegian picturebooks and comics in the Anthropocene. Doctoral dissertation, UiA, 2023. (The dissertation)

This article/press release is paid for and presented by the University of Agder

This content is created by the University of Agder's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Agder is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

See more content from the University of Agder:

-

Fear being rejected: Half pay for gender-affirming surgery themselves

-

Study: "Young people take Paracetamol and Ibuprofen for anxiety, depression, and physical pain"

-

Research paved the way for better maths courses for multicultural student teachers

-

The law protects the students. What about the teachers?

-

This researcher has helped more economics students pass their maths exams

-

There are many cases of fathers and sons both reaching elite level in football. Why is that?