An article from University of Oslo

Mending broken bones with food additives

A new invention helps the body generate new bone. Initially, this could help those suffering from loose teeth and damaged mandibles.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Periodontitis is a troublesome infection of the gums. When the infection causes the bone adjacent to teeth to break down, the teeth come loose. Mandibular bone can also be damaged by cancer, infections and accidents.

Broken bone usually repair itself, by generating new bone – although it does not always succeed.

“This is where our invention comes in,” says Ståle Petter Lyngstadaas at the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Oslo in Norway.

How it works

To understand how the invention works, we need to understand how the bone repairs itself:

When a bone fractures, a lot of blood collects at the site of fracture. Blood contains organic molecules that coalesce into long strands. This coagulum is then populated with cells and turn into connective tissue that later calcify.

The connective tissue functions as a porous growth platform for bone cells and blood vessels. The bone cells remodel the calcified structure and forms functional bone. New blood vessels help bring nutrients and oxygen.

The outer part of the bone is compact, while the inner part is porous. The porous part contains marrow cells, which are essential for maintaining the skeleton.

If there is too wide a gap between the two bone fragments, or if the bone has been damaged, the body might not be able to mend the bone.

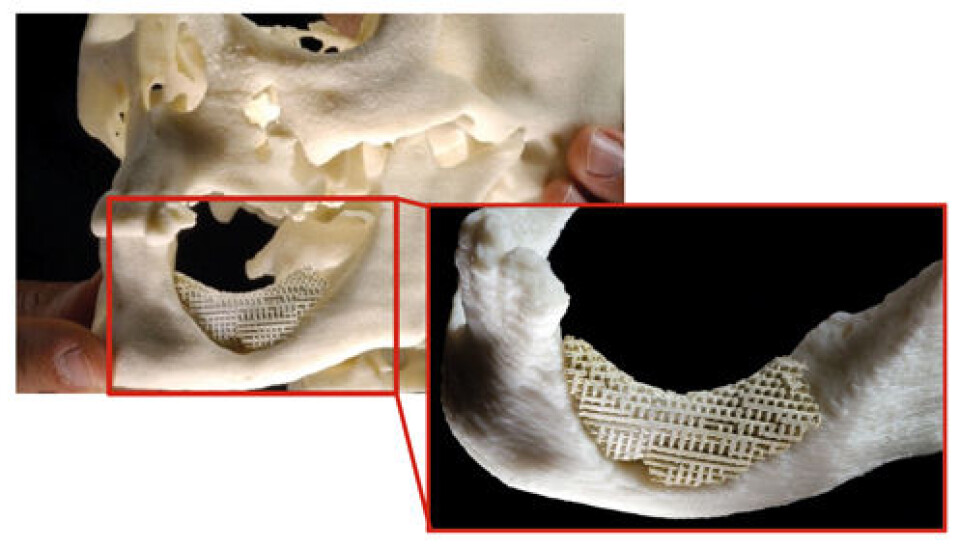

“With our new method, it’s sufficient to insert a small piece of synthetic, bone stimulating material into the bone. The artificial scaffolding is as strong as real bone and yet porous enough for bone tissue and blood vessels to grow into it and work as a reinforcement for the new bone,” says Lyngstadaas.

Speeding it up with stemcells

Associate Professor Håvard Jostein Haugen is also part of the project:

“To speed things up, we can take bone progenitor cells or bone marrow that contain committed stem cells from the patients and insert them into the scaffolding. This will cause the process to accelerate," Haugen says.

“However, stem cells are normally not required,” he underscores.

Made from food additives

Manufacturing the material easy. A mixture of water and ceramic powder is poured through foam rubber designed to look like trabecular bone.

The ceramic powder is also referred to as E 171, and is widely used in sweets, toothpaste, biscuits, baked goods, ice cream and cheese.

When the mixture has solidified, it is heated to a temperature that causes the foam rubber to dissolve into water vapour and carbon dioxide and the nano-particles to ligate into one solid structure. The structure is similar to that of the porous part of the bone.

Ready for clinical studies

The invention has been successfully tested the new method on rabbits, pigs and dogs.

Now Lyngstadaas, Haugen and their colleauges wish to undertake clinical studies on patients with periodontitis and damage to the mandibular bone.

To establish which method works best, it is advantageous to perform tests on patients with periodontitis in particular.

“The patients often suffer from bilateral periodontitis. This permits us to compare results by testing the material on one side and have the control on the other within in the same patient.”

The dentists hope that also the orthopaedists will take an interest in their new method.

“We are now looking for a large industrial partner who can scale up production and bring the product to the market,” says Lyngstadaas.