THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology - read more

Does adapting to a warmer climate have drawbacks?

When animals evolve to tolerate higher temperatures, those evolutionary changes might have other negative effects. Or maybe not.

Global warming is already very tough for animals in the wild, but it may be toughest for creatures like fish, whose body temperatures are controlled by the water temperatures around them.

Fish have to evolve to handle higher water temperatures if they are unable to move to areas with colder water. But what if adapting to warmer water has other unwanted consequences?

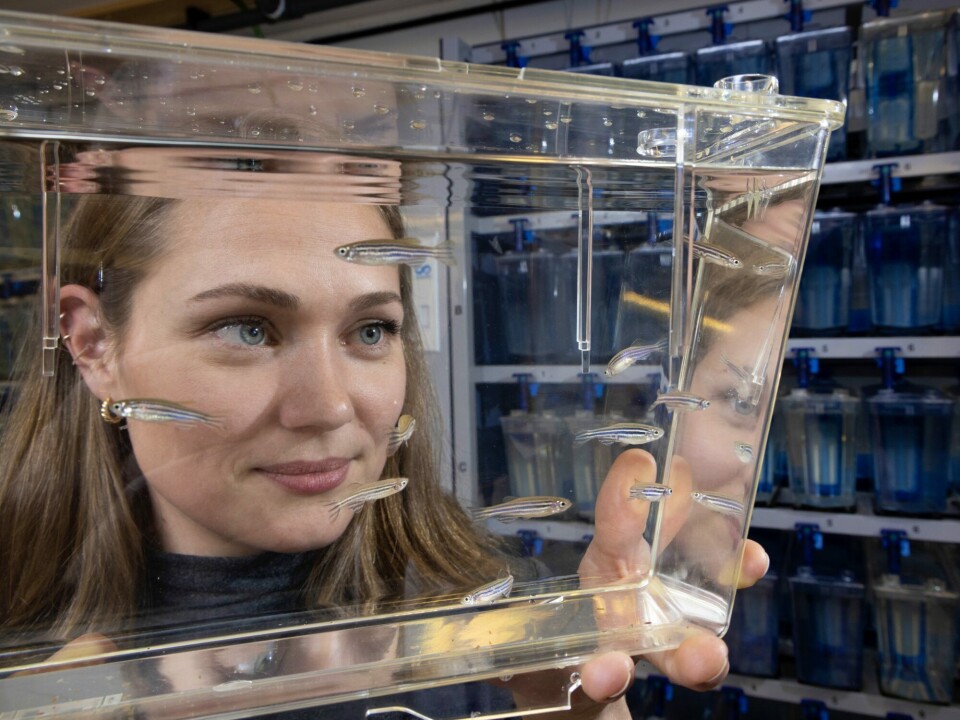

In a new study, researchers have looked at zebrafish that had been selectively bred over seven generations to tolerate higher maximum water temperatures.

“Very few research groups have been able to test how fish can evolve when facing climate change, because it takes thousands of fish and many years of careful experiments,” says Fredrik Jutfelt.

He is head of the Jutfelt Fish Ecophysiology Lab at NTNU.

“That makes this work very important because we can finally start to understand how evolution may help fish adapt to warming waters,” he says.

The study was designed to see if the higher heat tolerance would affect other aspects of the fish’s metabolism and ability to survive.

Surprising results

Much to their surprise, the researchers found that the fish that were bred to tackle warmer temperatures were also more tolerant of colder temperatures.

“What we normally expect, if we compare warm-adapted species in the wild, is that they have lower cooling tolerance. And then we saw this higher cooling tolerance, which was surprising,” says Anna Andreassen.

She was a PhD research fellow in the Jutfelt group at NTNU when she conducted this research, and is now a researcher at the Technical University of Denmark.

What was even more surprising for the researchers was that increased heat tolerance did not affect other aspects of the fish’s metabolism or ability to reproduce or swim.

A wild population from India

Andreassen and her colleagues designed their experiments to compare three groups from a population of wild fish collected in India and brought back to NTNU in 2016.

One group from this population was specifically selected for increased tolerance to high temperatures. A second, control group of ‘normal’ zebrafish was allowed to reproduce without any selection for heat tolerance. The third group from the same population was selected to be worse at tolerating heat.

After observing the change in warming tolerance, the researchers compared other traits among the three groups to see if being adapted to warmer temperatures gave fish a physiological or reproductive advantage or disadvantage compared to 'natural' fish from the same original group.

Oxygen is key

One test involved seeing how efficiently the two-centimetre-long fish used oxygen.

Just like in humans, higher temperatures increase the fish’s metabolism, meaning that individuals need more oxygen at higher temperatures.

One possible explanation for why heat-tolerant fish do better in warmer waters is that their bodies may use oxygen more efficiently than the control group or the fish with low heat tolerance.

“So one idea is that the heat-tolerant fish has some capacity to take up more oxygen than others,” says Andreassen.

Testing in a swim tunnel

To investigate further, the researchers placed the fish in the aquatic equivalent of a treadmill – a swim tunnel – where they could adjust the water speed and simultaneously measure oxygen consumption.

“We can measure how much oxygen they take up from the water while they’re swimming at their maximum capacity. It’s like putting them on little fish treadmills,” says Andreassen.

But much to their surprise, the researchers essentially found no difference in the use of oxygen among the groups.

There was one exception: The group that was bred to be more sensitive to high temperatures did not do as well as the other groups when temperatures were at their highest.

In short, Andreassen says that they did not see that oxygen played a role in helping fish tolerate warming in this case.

“And that's big in our field. One very big hypothesis is that global warming itself might not limit the animals, but that oxygen becomes limited at high temperatures. But we didn’t see that,” she says.

Swimming and having babies

The story was more or less the same when it came to other indicators of what defines a successful life for a fish.

The researchers thought there might be some kind of trade-off for tolerating higher water temperatures, so they looked at the commonly accepted indicators of what makes a fish well-adapted to its environment.

“When we look at how well they reproduce, and how well they grow and perform, we didn’t really see any trade-offs for the fish that had evolved to tolerate warmer temperatures,” says Andreassen.

That does not mean a trade-off does not exist, she adds, only that the researchers did not find one in the most commonly used measures of fitness they tested.

Better in a warming world?

Global warming means higher average temperatures, but it can also cause severe heatwaves. Researchers around the world are scrambling to understand if plants and animals can handle this additional stress – and if so, how.

It took three years for researchers in the Jutfelt group to breed their heat-tolerant zebrafish. But could wild populations evolve that quickly on their own?

Rachael Morgan, who also did her PhD using the same fish from the Jutfelt Lab, concluded in a 2020 article that there was a low potential for zebrafish to be saved by evolving to tolerate higher temperatures.

Nevertheless, Andreassen emphasises that it is important for biologists understand how these adaptations might actually come about.

“We’re trying to understand the physiology and what's actually changing in the body of the animals,” she says.

Jutfelt also points out that it is important not to overlook the larger problems that come with the warming of the planet.

“Even though the zebrafish didn’t show any adverse effects from developing a tolerance to higher water temperatures, climate change will nevertheless continue to pose unanticipated and dangerous challenges to all life on Earth,” he says.

Below, you can see a video of zebrafish and researchers in the wild:

References:

Andreassen et al. Evolution of warming tolerance alters physiology and life history traits in zebrafish, Nature Climate Change, 2025. DOI: 10.1038/s41558-025-02332-y

Morgan et al. Low potential for evolutionary rescue from climate change in tropical fish, PNAS, 2020. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2011419117

More content from NTNU:

-

Researchers now know more about why quick clay is so unstable

-

Many mothers do not show up for postnatal check-ups

-

This woman's grave from the Viking Age excites archaeologists

-

The EU recommended a new method for making smoked salmon. But what did Norwegians think about this?

-

Ragnhild is the first to receive new cancer treatment: "I hope I can live a little longer"

-

“One in ten stroke patients experience another stroke within five years"