This article was produced and financed by Institute of Marine Research

New sideswimmer discovered

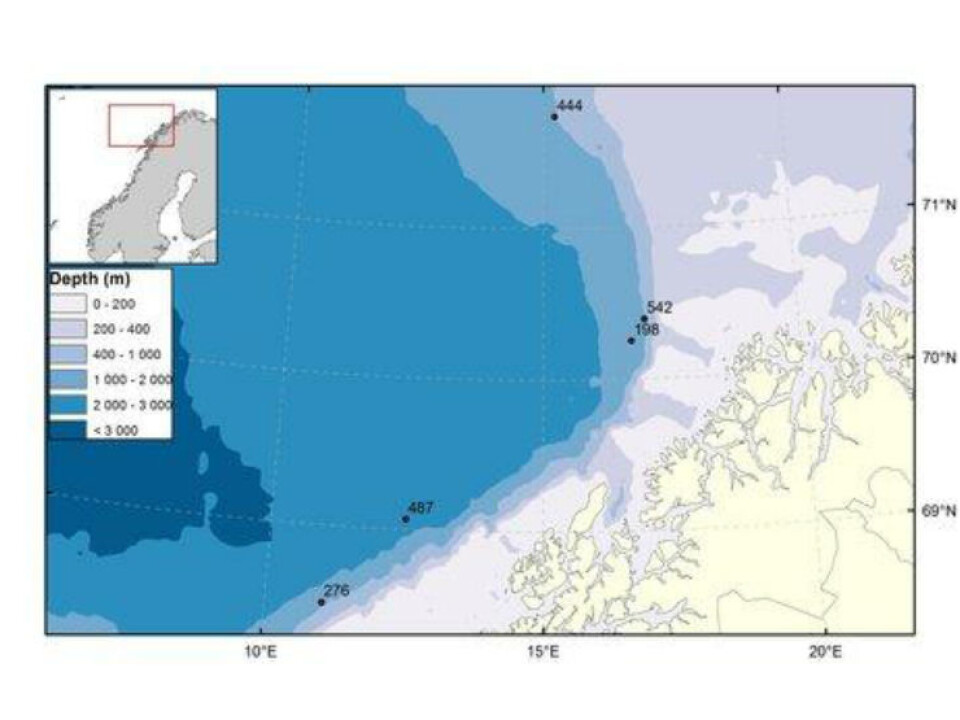

A new species of sideswimmers (amphipod) has been found on the continental slope off northern Norway. The new species is approximately 1 cm long, and appears to prefer water temperatures below 0 °C and depths of 1,000-2,600 metres. In total, 50 specimens of the new species were found.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

The sideswimmers is an order of small crustaceans whose many different species are found practically all over the world.

"One of the vernacular names in English is sandhoppers, this is based on the very few species that live in the upper littoral zone of sandy beaches, and that tend to jump a lot. Most amphipod-species, however, live in the sea on the seafloor (benthos). Of these marine species most might be familiar with the littoral species living between kelp and algae, this is again only a small fraction of the existing species," explains Anne Helene Tandberg, who was working as a scientist at the Institute of Marine Research when the new species was discovered. She has described the new species together with Halldis Ringvold from Sea Snack Norway.

The new species has been given the scientific name Halirages helgae.

"The species shares the characteristics of the existing Halirages genus, while helgae is a Latinisation of my mother’s name, Helga,” says Halldis Ringvold, who discovered the species, and therefore had the honour of naming it.

It is normal to use either a name that describes the animal, or the first name of a colleague, family member or some other person, generally deceased.

Found “everywhere”

Various species of sideswimmers are very common both along the coast and out at sea. The great majority of them live on the sea bottom, eating things that come down from higher up the water column.

"Amphipods are at the heart of the sea’s ecosystem, and you could say that their job is to recycle waste," says Tandberg.

Different species eat different kinds of nutrients that are found on the seafloor. These include planktonic algae, the excrement of animals swimming higher up in the water column, small animals that live in the sediment on the sea floor and dead fish and whales that sink to the sea bottom. They, in turn, provide food for other crustaceans, benthic fauna, fish, and birds.

Found while mapping the sea bottom

The samples where the new species was found were taken as part of the MAREANO project to map the sea bottom. This is an interdisciplinary project in which biodiversity, biotopes, sea depth, sediment types, and pollution are being recorded by the Institute of Marine Research, the Geological Survey of Norway, and the Norwegian Hydrographic Service. As part of this process the sea floor is being studied very carefully, which includes taking samples with a grab or sledge from selected stations on the sea bottom. The new species appeared in some of the sledge samples.

"The MAREANO project is surveying and mapping large areas of the sea bottom in unprecedented level of details, so it’s not surprising that new species occasionally appear, particularly of some of the smaller creatures living on or in the sediment," says Ringvold.

The process of how to describe a new species

The scientists working on MAREANO use a special tool called a hyperbenthic sledge to catch amphipods. The sledge is dragged along the sea bottom, and the animals that it catches are brought up on deck and kept in buckets. Later they are brought ashore and roughly sorted into basic groups such as crustaceans, molluscs, and sponges. Each group is then analysed and classified by specialists, and this is when new species are discovered.

"When we find an unknown species, it is the beginning of a time-consuming process. For an unknown animal to be recognised as a new species, the discovery must be published in a scientific journal in accordance with specific guidelines," explains Ringvold.

In the article, the information about the new species must be presented in a special, internationally approved format.

"Each species is given a scientific name, which has two parts, rather like a first name and a surname. These are called the genus and species epithet, and must both be in Latin," says Tandberg.

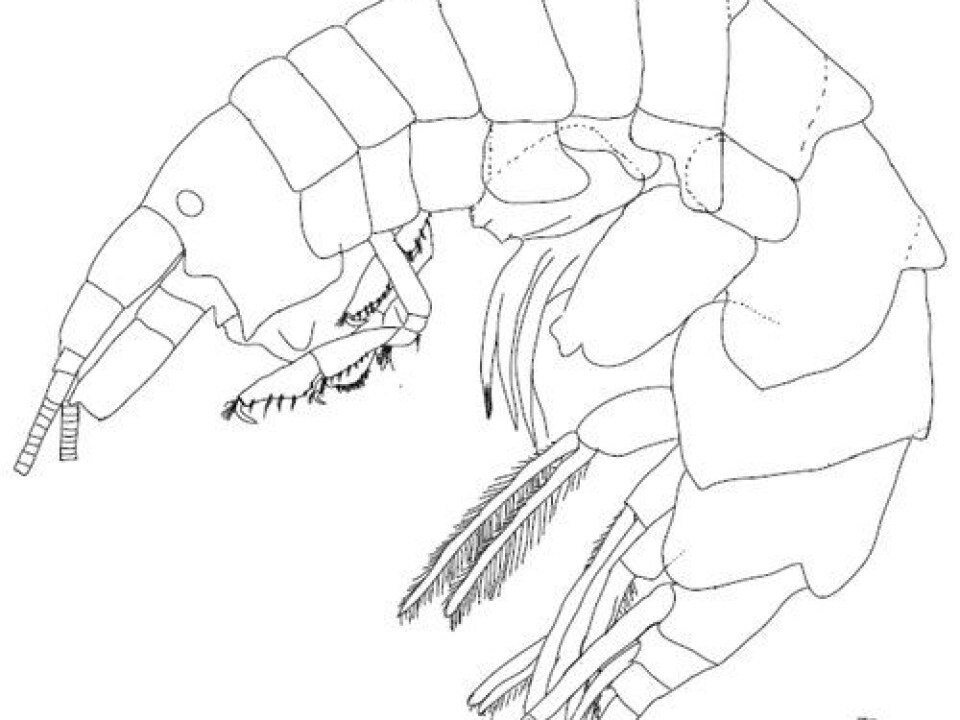

The whole animal must also be drawn in detail, all the way from its head and antennae down to its legs and tail. Once this has been prepared, together with a detailed scientific description of the appearance of each part of the animal, and why it is different from all other known species, the manuscript is sent to a scientific journal.

"The journal sends the manuscript to other, independent scientists, in order to get their views on the discovery. This is called peer review. The article will be published by the journal only upon approval by independent scientists. The whole process, from finding and describing a new species to publishing it, can take anything from a few months to a few years," says Ringvold.

Originals are sent to a museum

From the 50 specimens Ringvold and Tandberg picked out one Holotype (Original) and a few paratypes, which are representing the new species. They are all sent to a scientific museum.

"Our new species, Halirages helgae, was donated to Bergen Museum’s collection. The reason for keeping it in a museum is to enable other scientists to look at exactly the same specimens that we used to describe the species," says Tandberg.