An article from University of Oslo

Going after the aurora with rockets

Scientists are about to launch a rocket from the Svalbard archipelago in the Artic. The aim is to take readings within the aurora borealis, in order to investigate space weather and find out why GPS signals are disrupted.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Do you log your jogging trips with an app on your telephone? You’re not alone in using satellites to determine your correct position. Everything from snow ploughs to alarm systems relies on the GPS system.

But what happens when the GPS is incorrect, or doesn’t work at all? Not too serious for your jog, perhaps, but for other users accurate signals are crucial. That’s why it’s important to be able to forecast problems before they occur.

The aurora is a disruptive element

Solar storms create beautiful northern lights - the aurora borealis - in our atmosphere, but they also have a negative impact on navigation and communication systems. Serious users are in a particularly vulnerable position. Offshore activity, for example, is moving further north, and GPS is increasingly used in aviation.

“Both the aurora borealis and electron clouds that arise in the wake of solar storms create problems for radio communications and satellite navigation”, explains project manager and physics Professor Jøran Moen at the University of Oslo.

“It’s well known that solar storms cause disturbances, particularly in northern areas and around the equator”, he continues. ”But we still don’t know enough about the mechanisms that create these problems.

This knowledge is the key to improving GPS receivers and forecasting of space weather.

Aurora borealis in the daytime too

We usually think of the northern lights as a night time phenomenon, but they can be seen during the day too.

“On Svalbard, in the middle of winter and the polar night, when it is dark around the clock, we can see the aurora during the day,” explains Moen.

The aurora is not usually as spectacular during the day as it is at night, but it is still an important space weather phenomenon.

“We discovered ten years ago by means of radar studies that some very turbulent areas form at the edges of the daytime aurora”, says Moen. “Now we want to study in detail the effect this has on the atmosphere around the aurora”.

The aurora disrupts radio waves in all frequency bands The disturbances are greatest for radio communications in the HF, VHF and UHF frequency ranges, but they also cause problems for satellite services such as GPS.

We know that there are waves and turbulence at elevations of 200-1000 kilometres that spread and block radio waves, but scientists still have to find out what physical processes are causing this.

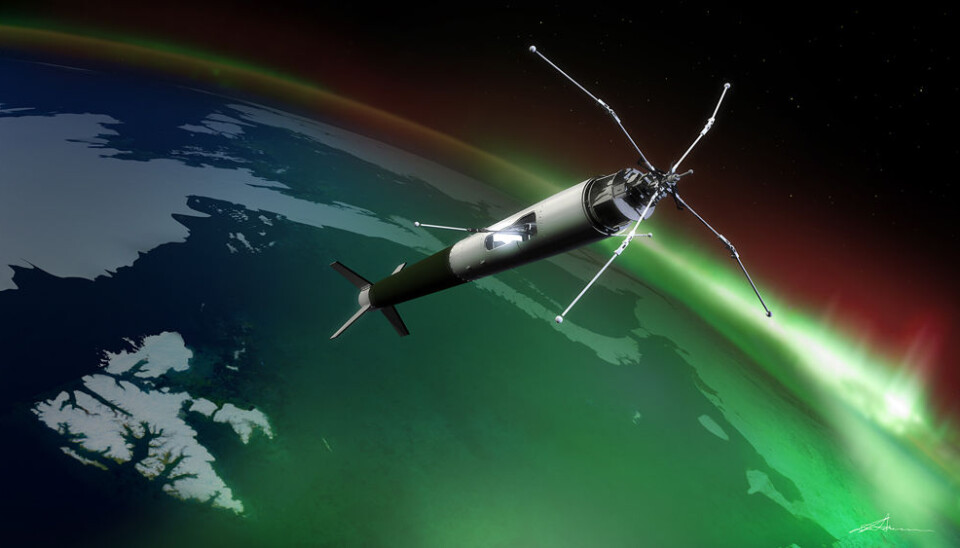

Designed to fly through the aurora

An international team of scientists participate in the rocket launch in Spitzbergen in the Svalbard archipelago.

The task of the ICI rocket is to gather data on what goes on in the daytime aurora, particularly in areas with extreme conditions. The rocket is equipped with a number of instruments for studying the electron clouds and electron rays that create the aurora.

French and Japanese scientists have also contributed instruments to the rocket, which will fly for 10 minutes up to a maximum height of 350 kilometres.

A successful launch will depend on a lot of factors falling into place.

“Both the weather gods and the sun god will have to be on our side”, jokes Moen.

The rocket can’t be launched if there is too much wind. The scientists also need the right kind of aurora, in other words the daytime aurora, in the area the rocket is going to fly in.

Some of the airspace above northern Scandinavia will be closed during the two-week window of time for the rocket’s flight. December 6 is the last date possible for the launch.