This article was produced and financed by University of Bergen

Art appreciation is measurable

Is it your own innate taste or what you have been taught that decides if you like a work of art? Both, according to an Australian-Norwegian research team.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Have you experienced seeing a painting or a play that has left you with no feelings whatsoever, whilst a friend thought it was beautiful and meaningful?

Experts have argued for years about the feasibility of researching art appreciation, and what should be taken into consideration.

Neuroscientists believe that biological processes that take place in the brain decide whether one likes a work of art or not.

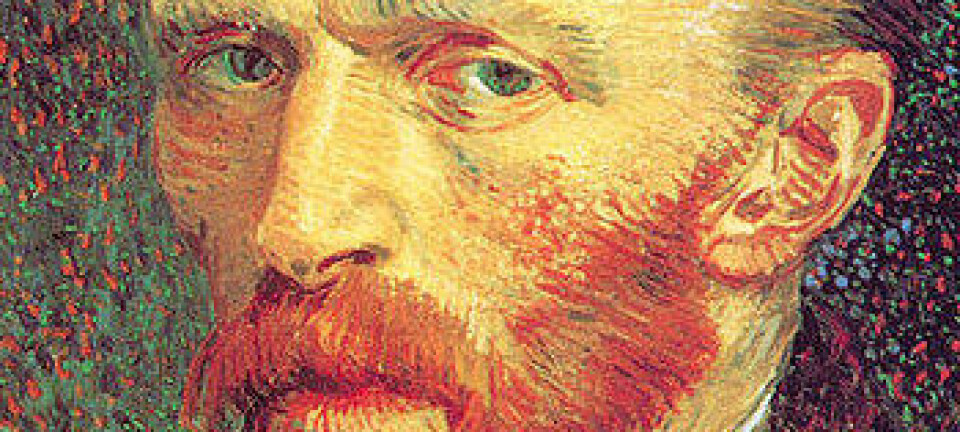

Historians and philosophers say that this is far too narrow a viewpoint. They believe that what you know about the artist’s intentions, when the work was created, and other external factors, also affect how you experience a work of art.

Building bridges

A new model that combines both the historical and the psychological approach has been developed.

"We think that both traditions are just as important, although incomplete. We want to show that they complement each other," says Rolf Reber, professor of psychology at the University of Bergen.

Together with Nicolas Bullot, doctor of philosophy at the Macquarie University in Australia, he has developed a new model to help us understand art appreciation. The results have been published in the journal Behavioral and Brain Sciences and are commented on by 27 scientists from different disciplines.

"Neuroscientists often measure brain activity to find out how much a testee likes a work of art, without investigating whether he or she actually understands the work. This is insufficient, as artistic understanding also affects assessment," says Reber.

Eye-opening experience

"We know from earlier research that a painting that is difficult – yet possible – to interpret, is felt to be more meaningful than a painting that one looks at and understands immediately. The painter, Eugène Delacroix, made use of this fact to depict war. Joseph Mallord William Turner did the same in ‘Snow storm’. When you have to struggle to understand, you can have an eye-opening experience, which the brain appreciates," explains Reber.

He hopes that other scientists will use the Australian-Norwegian model.

"By measuring brain activity, interviewing test persons about thoughts and reactions, and charting their artistic knowledge, it’s possible to gain new and exciting insight into what makes people appreciate good works of art. The model can be used for visual art, music, theatre and literature," says Reber.

Translated by: Anne Hermansen