This article was produced and financed by The Fram Centre

The ice retreats – whale food returns

This is good news for the bowhead whales in the waters around Svalbard, which almost became extinct in the 19th century. It could also put the Euopean whalers in the clear.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Due north of Svalbard is an area that is often called "Kvalbukta", or Whalers Bay.

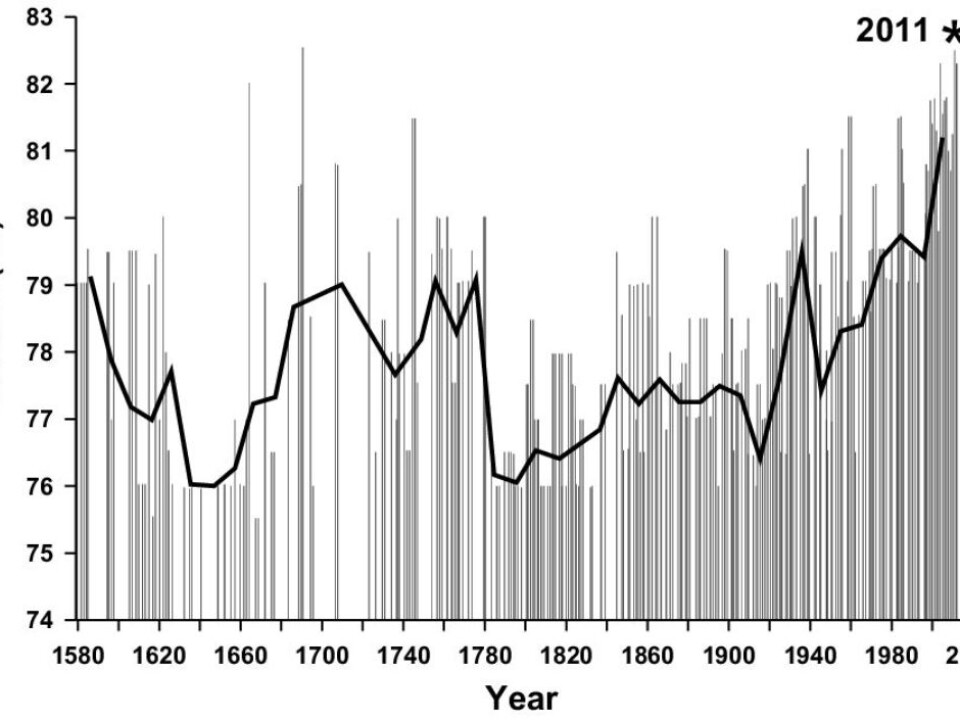

Between 1680 and 1800, this area was free of ice and had a biological productivity that provided a source of food for the huge numbers in those waters of one of the world’s largest animals, the bowhead whale, also known as the Greenland right whale.

For almost 150 years, Dutch and British whalers came to Whalers Bay on an intense hunt for the animal that brought enormous wealth.

European whaling and the bowhead whale

Between about 1670 and 1800, bowhead whales were intensively hunted commercially.

This whaling was so lucrative that several battles were fought for access to the whaling grounds, such as in 1693 when a great sea battle was fought in Sorgfjorden off Spitsbergen between two French frigates and at least 40 Dutch ships.

It also made the bowhead whale to become virtually extinct in the waters around Svalbard.

Or at least, that is what we all have been believing.

The ice destroyed the food source

Now, Norwegian researchers are seeking to throw new light on that explanation.

They believe there is another possible reason for the collapse of the whale population.

In the years between 1670 and 1800, the area north of Svalbard was ice-free, and thus similar to the situation researchers have observed in the past few years.

However, from 1800 and onwards, the north and west coast of Spitsbergen – the largest island in the Svalbard archipelago – gradually became covered in ice, destroying the food source which sustained the stocks of bowhead whales.

The expansion of ice led to the effective blocking of warm and nutrient-rich water welling up from the Atlantic Ocean. The ice also prevented sunlight from penetrating the water, which is necessary for phytoplankton, or plant plankton, to bloom.

Return of sunlight

The two most important factors that regulate the growth of phytoplankton – nutrients and sunlight – were therefore restricted for a period of almost 150 years.

In recent years, the ice has retreated north and away from the arctic shelf break, and we again have a situation in which both nutrient salts and sunlight are available in Whalers Bay.

This also means that the zooplankton Calanus glacialis are becoming more numerous, providing an abundant food source and conditions to sustain new generations of bowhead whale.

The basis for biological productivity has thus been restored, and the bowhead whales remember their old migration routes.

Finding their way back along old migration routes

Up until the year 2000, only a few tens of bowhead whales were recorded in the area.

In 2004, the two marine mammal research scientists, Kit Kovacs and Christian Lydersen, succeeded in attaching a radio transmitter to a bowhead whale.

This enabled them to show that the whale followed the old migration route along the coast of Greenland and north to Whalers Bay off Spitsbergen.

“Our hypothesis is that the conditions are now right for an increase in the bowhead whale population, and that the food supply north of Svalbard is the treasure chest that the surviving bowhead whales are looking for in their migration across the North Atlantic and into the Arctic,” explains research scientist Stig Falk-Petersen.

Nutrient-rich water

The Arctic Ocean, including the Fram Strait, has been regarded as an area with low biological productivity.

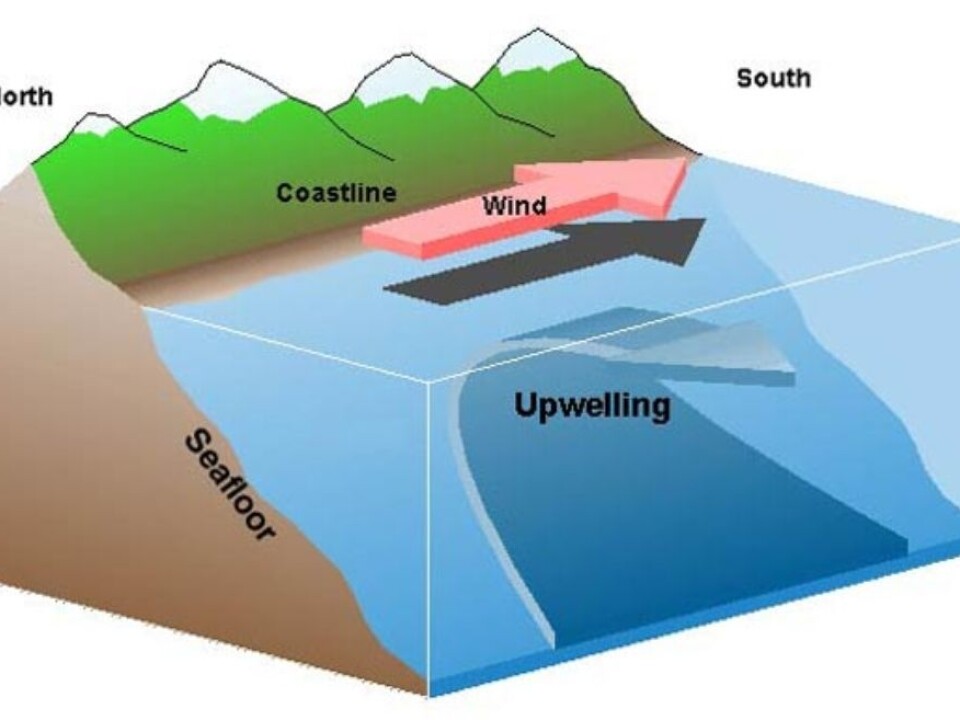

Russian and American research scientists have, however, demonstrated that if the ice retreats off the arctic shelf break in winter, warm Atlantic Water will well up from the deep – so-called “upwelling” (see illustration).

Upwelling is a kind of vertical mixing of water masses that occurs under specific conditions in the ocean, and which leads to colder, denser and nutrient-rich deep water rising up and replacing the surface water.

Fridtjof Nansen was the first person to show how the waters of the Atlantic continued into the Arctic Ocean at relatively great depths. Later surveys done by the Russian drifting ice research stations which began as early as the 1930s, showed that the Atlantic Water follows the depth contours around the entire Arctic Ocean, and streams out on the east side of Greenland at a depth of 600 to 900 metres.

Water column

During a research cruise in January 2012, Falk-Petersen and colleagues demonstrated for the first time that there was a massive upwelling of warm water along the arctic shelf break.

What they describe as a column of warm, nutrient-rich water was welling up from a depth of 500 metres as far east as off Nordaustlandet, the second largest island in Svalbard.

The Norwegian researchers show that the basis for this column effect is the combination of ice-free areas along the arctic shelf break on the north side of Svalbard and winds from the east-northeast.

The food is back

When a low atmospheric pressure system forms above the Norwegian Sea, followed by strong winds from the south and west, the wind circulates around the centre of the low pressure system and comes from the northeast, north of Svalbard.

Because of the Earth’s rotation, the direction of the drifting ice and the surface water is moved to the right, i.e. away from the north coast of Svalbard. As a result, there is a transport of surface water and sea ice away from the coast. This transport is then compensated for by warm, nutrient-rich Atlantic Water welling up from the deep.

“We also identified large quantities of the fat-rich Calanus glacialis, which is the food of the bowhead whale, in the upper water layers. This study shows that there is an abundance of nutrient salts present, so that phytoplankton starts blooming when the sun returns in March. The phytoplankton are in turn food for Calanus glacialis. The conclusion is that the food of the bowhead whale is back,” the authors state.

The project is funded by the Research Council of Norway through the Marine Night projects.

------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no