This article was produced and financed by The Research Council of Norway

Chaotic current warms Norway

The Gulf streams warms Norway and Northern Europe. It is the chaos of the seas that does the trick. The current would deliver far less warmth if the waters flowed smoothly.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Norway is situated at the same high northern latitude as Greenland, Northern Canada and Northern Siberia, but thanks to The North Atlantic Current – popularly known as the Gulf Stream, its climate is significantly more temperate.

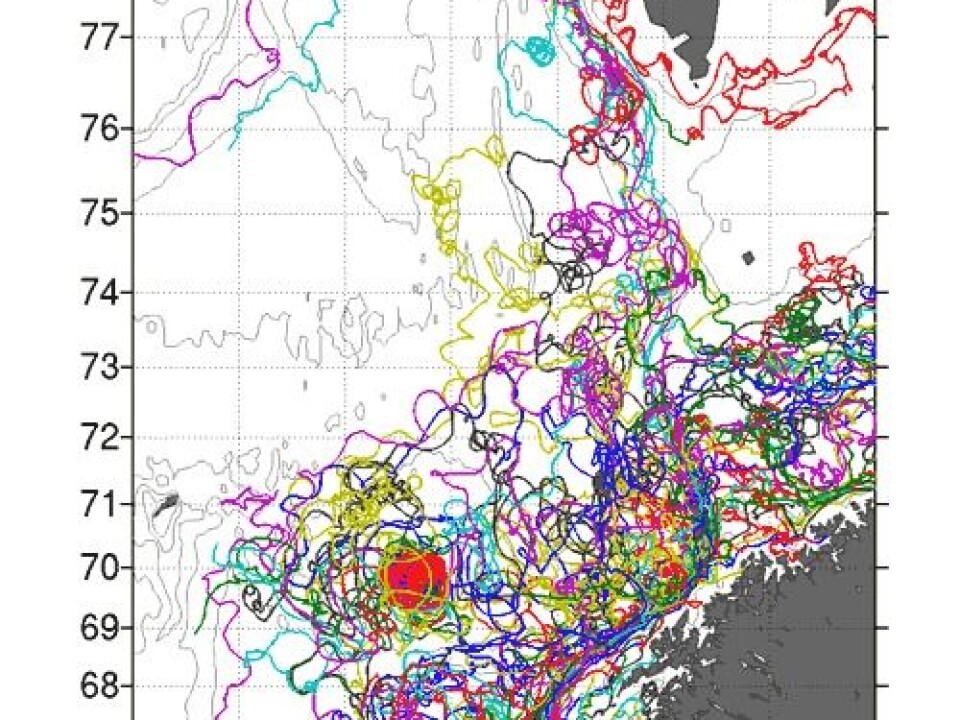

By deploying 150 marine buoys tracked by satellite, researchers in the POLEWARD project have been able to chart in detail how the current flows northward along the Norwegian coast.

The buoys revealed that the current often travels quickly, but because it is so irregular and thus highly variable – indeed, chaotic may be the best description.

The Gulf Stream’s journey takes perhaps as much as ten times longer than it would if it flowed smoothly.

In this way there is time for the warm ocean current to convey a vastly greater proportion of its heat into the atmosphere, from which the warm air is carried on the predominantly westerly winds towards mainland Norway.

Current takes 500 days

If the Norwegian branch of the North Atlantic Current flowed evenly, it would surge past Norway at a speed approaching one metre per second, roughly as fast as many rivers run. At that rate, the waters would need only 60 days or so to travel the length of Norway’s mainland and reach Svalbard.

This would mean that less of the current’s heat would be transferred to the atmosphere, resulting in a substantially colder climate.

Scientists have now discovered that the current takes more than 500 days to flow past Norway, giving the waters more time to release their heat and warm up the country.

Chaos models

The researchers studied how simultaneously deployed buoys drifted away from one another, observing that their trajectories were in line with different chaos theories at different stages of their journey.

“In much the same way as biologists track migratory birds, we were able to chart the movements of the current’s water particles through the Norwegian Sea,” explains POLEWARD project manager Cecilie Mauritzen.

"We now have a very clear picture of how the northeastern extension of the North Atlantic Current flows north along the coastline."

Dr. Mauritzen is director of the Climate Division at the Norwegian Meteorological Institute in Oslo.

Chaos explains climate

When watching the tiny particles of water, oil or ash in motion, it may appear they are moving along smoothly. But in reality their movements are always more or less chaotic.

The disorderly movement of the ocean current off the Norwegian coast is an example of turbulent advection – streams that do not move in a uniform line of flow.

Other examples include the dispersion of ash from Iceland’s Eyjafjallajökull eruptions and the dispersion of oil from BP’s Deepwater Horizon leakage in the Gulf of Mexico.

Greater insight into this apparent chaos can help scientists to develop better climate models. Not least they will better understand how heat is transferred from the ocean to the air, helping to define the role of oceans in global climate.

From cold to colder

As the Norwegian Atlantic Current flows northward between Scotland and Iceland, it forms a layer that is a couple of hundred metres deep and 8-10°C. Along the western coast of Norway, much of the current’s water mass follows the continental slope before dividing into two branches when it reaches Troms County.

The smaller branch continues on to the Barents Sea, the larger one to the Fram Strait between Svalbard and Greenland. At this point the ocean temperature has dropped to well below 5°C.

After releasing a tremendous amount of its heat, the current dives beneath the cold Arctic waters.

Eventually the current flows back to the Atlantic at a depth of 4 000 to 5 000 metres and can remain submerged at that depth for hundreds of years as it circulates in the world’s oceans.

Translated by: Darren McKellep/Carol B. Eckmann