THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY the Fram Centre - read more

Is the Arctic warming faster than the rest of the world?

A recent report from 97 researchers shows drastic changes.

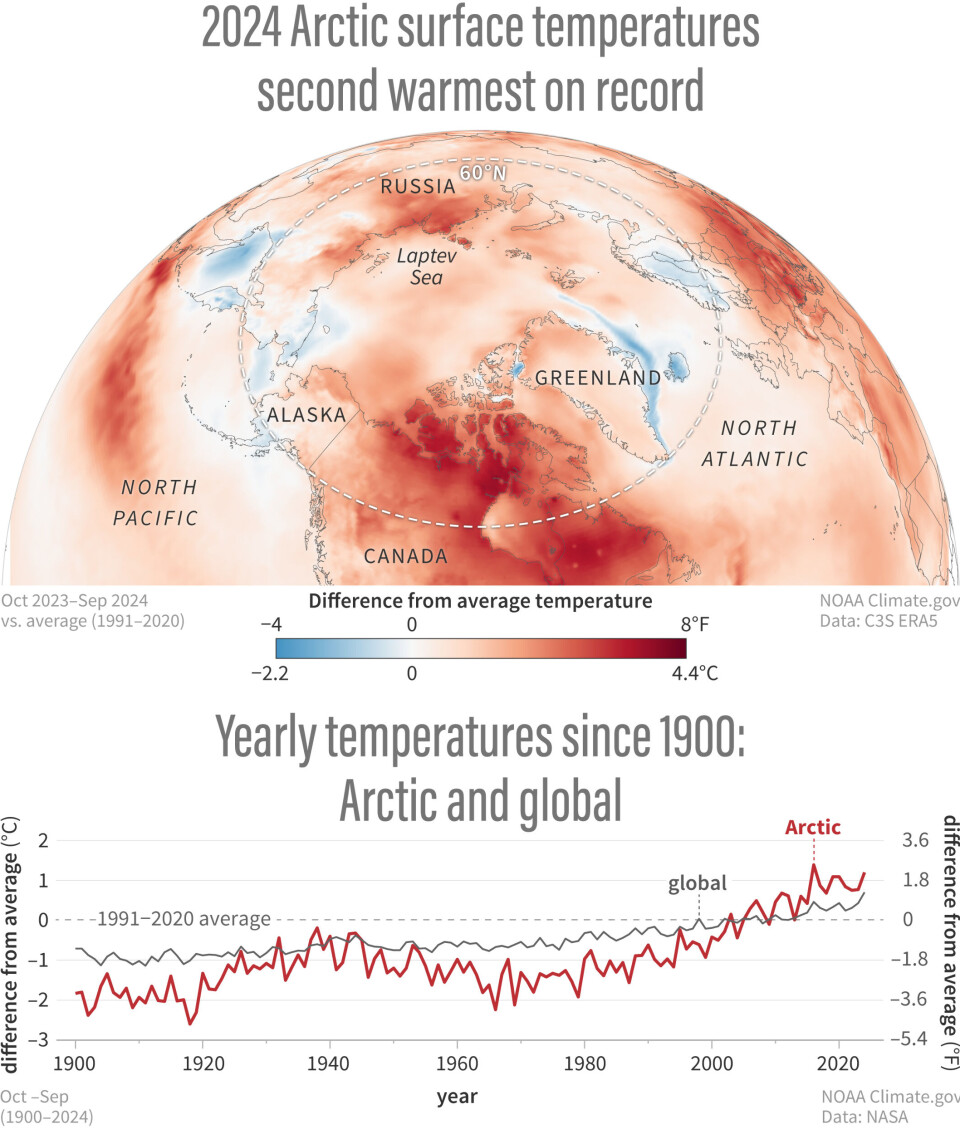

The Arctic continues to warm at a faster rate than the global average. This is shown in the recent Arctic Report Card for 2024, prepared by 97 researchers.

In the report, they highlight that the last decade has been the warmest decade in the Arctic, and that the past year was the second-warmest since recording began in 1900.

“We also saw this at our Arctic stations, and especially the summer of 2024 was very warm. In August 2024, previous high temperature records were broken by several degrees Celsius at all the Arctic stations. And at Svalbard Airport, for the first time ever, the temperature recorded for August was over 20°C,” says Herdis Motrøen Gjelten.

She supplies temperature data from the Norwegian Meteorological Institute’s stations in Svalbard and Jan Mayen.

Changing tundra

The Report Card also describes the transformation of the Arctic tundra. Multiple wildfires have accelerated this change.

When the impact of increased forest fire activity is included, the Arctic tundra region has gone from being a carbon sink to becoming a carbon source.

This means that as the tundra warms, more CO₂ will be released, causing further climate change.

Emissions from wildfires in the Earth's polar regions have, on average, amounted to 207 million tonnes of carbon per year since 2003.

The report also describes a decline in what were once vast reindeer herds, particularly in North America. It also describes increased winter precipitation.

The researchers' observations also reveal regional differences. This means that people locally and regionally experience environmental changes very differently, affecting humans, plants, and animals.

Adaptation is becoming increasingly necessary. The report stresses that indigenous knowledge and community-led research programmes are crucial for understanding and responding to rapid Arctic changes.

Svalbard is becoming greener

Several Norwegian researchers participated in the report. One of them is senior researcher Hans Tømmervik at the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA) at the Fram Centre.

He says that NINA has been involved in this work continuously since 2016. Their ground measurements on Svalbard are used for ground calibration.

Tundra greenness is a measure of productivity. Across the polar regions, it was measured at its second-highest since 2000.

The Norwegian Arctic includes Svalbard, Bear Island, Jan Mayen and coastal Finnmark.

The eastern and coldest regions of Svalbard, such as Edge Island, are showing the greatest increase in greenness since the start of the time series in 2000.

“This is consistent with the retreat of glaciers and reduced sea ice in the Barents Sea. But the regions down to 60 degrees north that comprise most of Norway, Sweden and Finland have also shown increased greenness over the same period of time,” says Tømmervik.

Meanwhile, some areas in Sweden and Finnmark are showing reduced greenness due to forest damage caused by insects, birch moth outbreaks, and fungi.

The greatest reduction in greenness is occurring in eastern Siberia, which is impacted by forest fires.

Moreover, melting permafrost means more bodies of water. Fire and water together are responsible for the decline in productivity.

Less sea ice

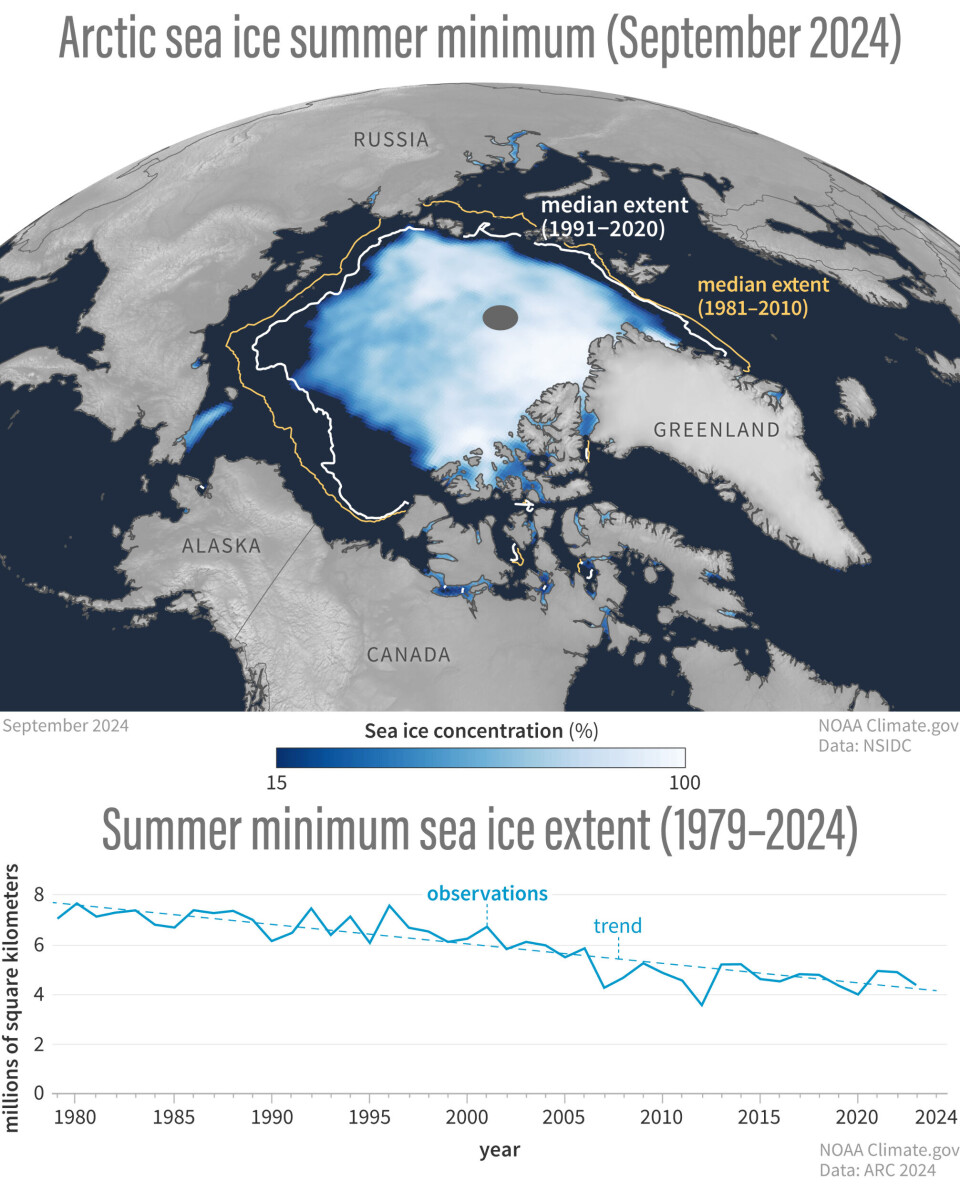

Researchers from the Norwegian Polar Institute have contributed to the report on Arctic sea ice since 2012.

They report that the minimum extent of Arctic sea ice in 2024 was the sixth-lowest in 45 years of continuous satellite observations.

The 18 lowest annual sea ice year extents (of 45) have all occurred in the last 18 years.

“It’s exciting to have the opportunity to contribute to the Arctic Report Card and collaborate with international sea ice researchers. This work is an opportunity to put our long-term sea ice observations in the Fram Strait, the Barents Sea, the Arctic Ocean and Svalbard in a bigger context,” says Sebastian Gerland from the Norwegian Polar Institute.

Reference:

Arctic Report Card: Update for 2024, Report from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration i USA, 2024.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

This content is paid for and presented by the Fram Centre

This content is created by The Fram Centre's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The Fram Centre is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

More content from the Fram Centre:

-

Nature's cathedral: People have gathered in this cave for at least 10,000 years

-

Puffin hunting in Iceland gives a unique insight into climate effects

-

Larger areas of ocean in the Arctic must be protected

-

Pink salmon: problem or resource?

-

Chemicals from rubber playgrounds and artificial turf pitches pollute the sea

-

Carbon emissions have made the world a greener place, which has a cooling effect – but it’s not enough