This article was produced and financed by University of Bergen

World’s oldest engravings discovered in Java

According to a new study of freshwater shells from the Indonesian island of Java, early hominins created geometric engravings 450,000 years ago.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

When a team of archaeologists studied bones and freshwater shells from the Trinil region of Java, collected more than 100 years ago, they were surprised to find that one of our ancestors, Homo erectus (known more commonly as Java Man), used shells for tool production and engravings as early as 450,000 years ago.

An early emergence of modern cognition

The researchers have not determined the function or meaning of the engraved shell, but this discovery suggests that the engraving of geometrical patterns was a behaviour practiced by Asian Homo erectus at the time.

“The production of abstract representations is generally considered a behaviour reflecting modern cognition. This discovery shows that we may share more attributes with our early ancestors than previously thought,” says Professor Francesco d’Errico of the Department of Archaeology, History, Cultural Studies and Religion at the University of Bergen (UiB).

The oldest geometrical engravings found before the Java discovery are those from Blombos Cave in South Africa’s Western Cape region. These engravings are about 100,000 years old and were produced by modern humans. This latter discovery was made by the TRACSYMBOLS research team, of which Professor d’Errico and Professor Christopher Henshilwood are the principal investigators.

“It is generally accepted that early modern cultures originated in Africa, in parallel with the emergence of our species in that continent. New discoveries suggest that the story is more complex and that other hominins may have displayed to a degree or another some of these capacities,” says d’Errico.

The UiB archaeologist is part of the research team that discovered and analysed the engravings found in Java. Their results are published in the journal Nature in December 2014.

Rediscovering ancient shells

The Dutch palaeoanthropologist and geologist Eugène Dubois discovered the shells in 1891, in the same archaeological layers that have yielded the remains of Pithecanthropus erectus, later named Homo erectus. d’Errico and his research partners found the evidence in the Dubois collection at the Naturalis Biodiversity Centre in Leiden in the Netherlands.

The engravings were found by accident, when a student of marine biology studied the fossil shells.

“The study of the pattern required the expertise of archaeologists working on the earliest examples of symbolic behaviour. This is the reason for me to be part of the study,” says d’Errico.

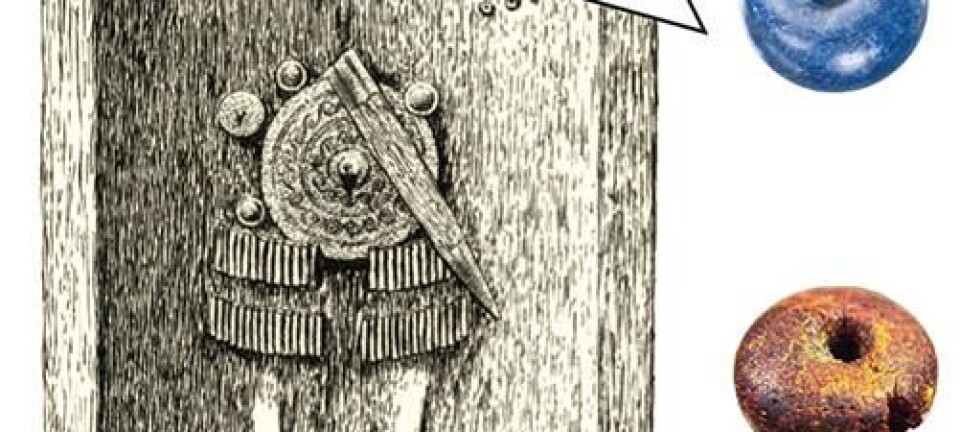

One of the 166 shells in the collection showed an engraved zigzag pattern, which cannot have been produced by natural causes. Using two luminescence dating methods, the researchers have shown the engraved shells to be about 450,000 years old.

“Our analysis and experimental reproduction of the engraving on similar shells reveals that the whole pattern was engraved by a single tool, during a single session, and that the engraver knew what he was doing,” d’Errico suggests

The researchers found that marks made by shark teeth most resemble those composing the original engravings. Fittingly, a large number of shark teeth were found during the excavation at Trinil.

Shells used as tools

Among the other shells in the collection, the researchers have identified a valve that has been modified by retouching the edge to be used as a tool to perform cutting and scratching actions, perhaps to produce tools made of perishable material, such as bamboo.

“This may explain why tools made of stone are rare in some regions of Asia, while millions of stone tools have been found in Africa at sites dated to this period,” says d’Errico.

The earliest oyster knife

Most of the shells also have a small hole at the location of the abductor muscle insertion. Using a sharp object to drill holes in the shell and detach the muscle, Homo erectus could easily open the shells and have access to the meat.

“This technique is very effective and works better than opening the shells with a knife. It implies that in order to invent this technique Homo erectus had a good knowledge of the mussel anatomy and communications skill allowing him to transmit the technique to new generations,” says Francesco d’Errico.

“These shells were at the same time a source of food, raw material and a canvas for abstract expression. For this reason they reflect a cognitive plasticity that many would have not attributed to Homo erectus before our discovery.”

Translated by: Sverre Ole Drønen