This article was produced and financed by the University of South-Eastern Norway - read more

VIDEO: See the board games Vikings used to keep their minds sharp

The strategy game of hnefatafl, a sort of asymmetric chess, was popular in the Viking Age. And this was more than a mere pastime.

Did you know that the Vikings often played board games? Archaeologists have found many different pieces as well as boards. These games also appear in a number of original texts, such as the Voluspå poem and in sagas such as the Orkneyinga Saga, the saga of Fridtjof the Bold and the saga of Hervor.

"Board games were undoubtedly popular in the Viking Age. Game pieces in particular occur frequently in grave findings, while boards are more rare," says Bjørn Bandlien, professor of history at the University of South-Eastern Norway.

Viking board games are called ‘tafl’ games, where ‘tafl’ can be translated as ‘board’. Apparently, the most popular game was called hnefatafl, which is often translated as ‘the king’s table’.

"The meaning of 'hnefa’ is uncertain, but most philologists point towards 'fist'. 'Fist board' probably has a sounder etymological basis, but may not sound as good as the king’s table", says Bandlien.

(For English subtitles press the subtitle icon in the lower right hand corner)

The Vikings spread the game

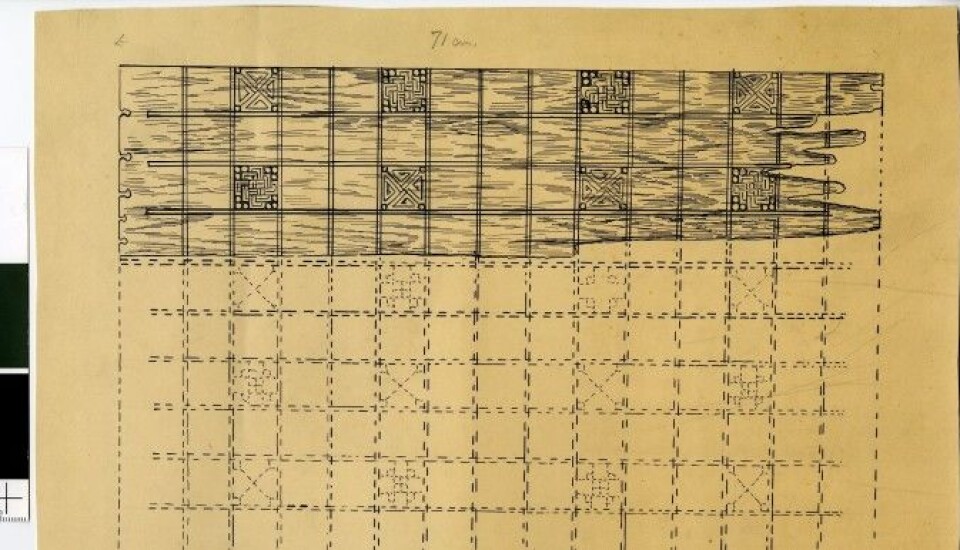

The relatively few game boards that have been found include fragments of an oak board dating from around the year 910 in the Gokstad burial mound near Sandefjord.

The board has a grid of 13 x 13 squares on one side, and this has been interpreted as hnefatafl. On the other side of the board was a game of mills. This is the only game board that has been preserved from Viking Age Norway.

Professor Bandlien’s personal favourite stems from a find in Ballianderry in Ireland and dates from around 950.

The Vikings did in fact bring their games with them when setting out in their longships, and different versions have been found in excavations from Ireland in the west to Ukraine in the east.

The design of the pieces and boards varies, so most likely there have been many variants of the game we know as hnefatafl.

"The archaeologists have obviously never found a rule book, so that today, hnefatafl is played in many different ways, as we can assume that the Vikings also did," says Bandlien.

The efforts to reconstruct the rules for hnefatafl have been based on notes made by the Swedish botanist Carl von Linné at the age of 25 during a field trip to Lapland, when he came across some Sámi farmers who were playing a board game they called ‘Tablut’.

Linné’s diary notes are simply the oldest known description of a tafl-type game.

The game reflects a battle situation

In brief, hnefatafl is about a Viking king who is besieged in his fortress. The attackers outnumber the king’s men two to one. The king must escape before his opponents can encircle him.

In this way, the players have different goals and frameworks for the game depending on the pieces they control. In contrast to chess, the king is the strongest piece on the board in hnefatafl.

The game thus reflects a battle situation, where it can be hard to keep an overview, many outcomes are possible and one player can quickly gain advantage over the other.

Quarrels could have a fatal outcome

Hnefatafl was not merely a pastime; being good at it gave a player status. The elite liked to appear not only as warlike and brave, but also as eloquent, quick-witted and with poetic talent.

"They wished to appear as wise, knowledgeable and intelligent. Board games were obviously an opportunity to have a battle of wits," Bandlien explains.

Board games also seem to have featured in Viking social gatherings. The game functioned as an expression of good-natured competition. But then as now, board games could become tense and cause tempers to flare.

"Quarrels could occur over the game board, especially if one of the players felt dishonoured. For example, we know that King Canute the Great is said to have killed an earl after a round of board games," says Bandlien.

Related: ’Twas dangerous to insult a Viking

Displaced by chess

Despite of its widespread use and popularity, hnefatafl gradually faded from view until it more or less disappeared completely some time during the Middle Ages, when it was displaced by chess.

"Chess arrives some time during the 12th century. At first, it is played primarily in royal courts around Europe, but is gradually introduced at the Norwegian royal court as well. Royalty and the king’s men needed to be in command of this game in order not to appear as bumpkins to emissaries from other countries," Bandlien explains.

From the same period, archaeologists have found other board games that are reminiscent of Viking Age hnefatafl.

"From the 12th century onwards, these games are associated with the lower social strata, and could be found, for example, in taverns in the towns. The 13th century text Konungs skuggsjá (‘King’s Mirror’) specifically warns men against engaging in 'drinking, tafl and harlots' – and it is hardly chess that is meant," Bandlien concludes.

———

(For English subtitles press the subtitle icon in the lower right hand corner)

(For English subtitles press the subtitle icon in the lower right hand corner)

(This video does not have English subtitles - but perhaps fun to watch the game being played anyways?)

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no