An article from NIKU - Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research

The secrets of St. Clement’s church

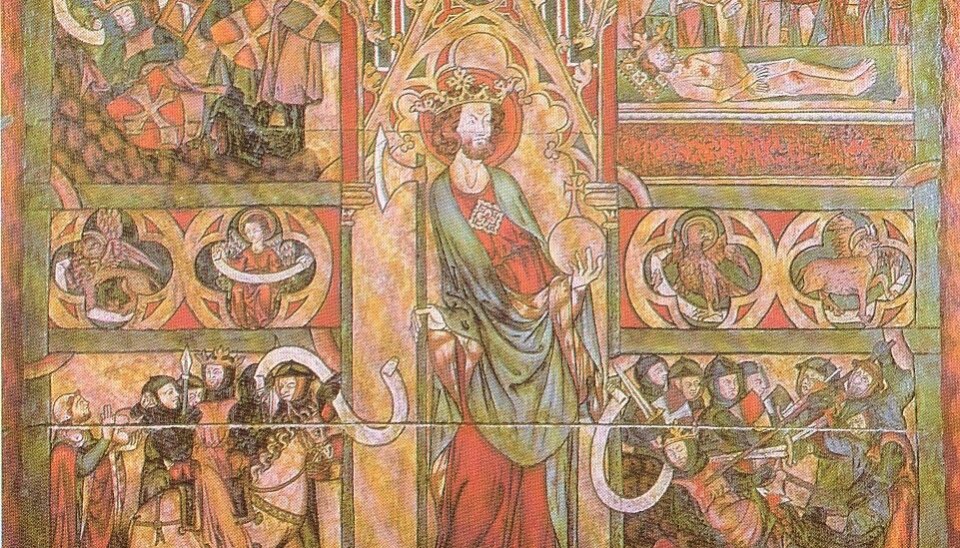

A fascinating and complex history of the church has been uncovered, beginning with the original wooden church and leading to a sequence of three major rebuildings, corresponding in time with the transformation from Viking king Olaf to the royal saint St. Olaf of Norway.

After more than a year of continuous archaeological investigation, a major excavation in the centre of Trondheim was completed in October 2017. Trondheim was the first capital of medieval Norway and the excavation has provided us with a whole new knowledge base for research into the city’s history.

In the autumn of 2016, archaeologists made the sensational find of remains of St. Clement’s Church. Enough of the foundations survived to show that it had been a stavechurch, and many of these fine medieval buildings – both simple and elaborate – still stand in Norway today.

An early theory which developed was that the excavation had found the site of St. Clement’s Church, founded by King Olav Haraldsson in around AD 1015. He was one of the first Christian kings of Norway and would become (and remains) the country’s patron saint.

"We soon saw that the church site was far more complex than at first thought. The remains of the church lay on over 2 metres (6½ feet) of earlier archaeological remains, but also we saw that some of these were in fact the remains of at least one earlier church," says archaeologist and project leader for the excavation Anna Petersén.

St. Clement’s church – foundation, fires and rebuilding

As the excavation proceeded through the spring of 2017, it became clear that there was a long tradition of church-building on this spot. The stavechurch seen the previous year was actually the last of a series of four churches, each built on the same site over the remains of its predecessor.

All of the churches were unique in their method of construction, but all four were constructed mostly of timber. The full length of these churches has not been fully excavated, as the western end of each lie under a standing building.

"The earliest church was constructed with massive wooden corner posts, up to 45cm (1½ feet) in diameter, but its walls would have rested on flat stones, and this technique is known from other early churches in Scandinavia," says Petersén.

The excellent preservation allowed the use of dendrochronology (tree ring dating) for two of the timbers of the church, and both were felled in AD 1008 or 1009. One of the timbers had been cut to be a horizontal sill beam, but had been used in the church as a corner post instead, perhaps indicating it was intended for another building, or a last minute change in design of the church.

"The precise dating of these original timbers allows us to be as confident as we can that this was the church built by Olaf Haraldsson and dedicated to St. Clement," says Petersén.

Olaf Haraldssons body exhumed and placed in St. Clement’s church

Later sagas and church histories say that after Olaf was killed in battle, his body was first hidden in the town, then buried close to the church, and a year later exhumed and placed in his church of St. Clement.

As the cult of St. Olaf grew in importance, his remains were first moved to a church built by his son King Magnus and dedicated to his father, and again moved from St. Olaf’s church to the newly-founded cathedral of Trondheim (begun in the mid 12th century).

The rebuildings of St Clement’s parallel the change of place of the shrine, show that the site of his original church continued to be venerated.

This earliest church had one final secret to reveal. While excavating the wooden posts, several pieces of a finely-carved soapstone font were found, the pieces packed around each of the posts and used to steady the timbers during construction. If this is indeed the Church of St. Clement, how can an earlier font have been used in its own construction?

According to one of the sagas, the town of Trondheim was founded by an earlier king, Olaf Tryggvason (AD 995-1000), who may also have built a church.

"It has been argued that this church was in fact St. Clement’s, but if the earliest church dates to St Olaf’s time, the fragments of the font are the best physical evidence for the existence of Olav Tryggvason’s church, and that this church lay somewhere else in the town, though perhaps close by," says Petersén.

The exact fate of the first St. Clement’s is unclear, but a second church was constructed over its remains. This survived as the stone foundation wall for a stavechurch – a single row of stone blocks on which the wooden walls would have rested, with a square stone altar at the east end of the chancel. Research is continuing on when exactly this church was constructed, but it is clear that the building had burnt to the ground, with scorch marks visible on the stonework.

After the fire, the burnt timbers had been carefully removed, the stone foundations left in place but covered in layers of river sand and a new, third church constructed. This used wooden posts again, although the altar was increased in size using slabs of green stone and white marble.

Dendrochronology of these posts revealed that the timbers were mostly cut in AD 1220 or 1221.

The wooden city

Medieval Trondheim was a wooden city (and its historic centre still contains many impressive timber buildings). A number of major fires are recorded, but the second known ‘great fire of Trondheim’ occurred in the year 1219.

"This suggests that the second church was destroyed in this fire (which was said to have burnt the entire city), and that the third church was built in the years immediately after," says Petersén.

After the third church went out of use, perhaps again as the result of a fire, the fourth and last church was built on the same spot, perhaps in the late 13th century.

This was the stavechurch identified back in 2016 and when this church also burned down, it stood as an open ruin, although the cemetery continued to be used, especially for the burial of infants. The archaeological evidence suggests that no new buildings were established on the site until the late 16th or early 17th centuries.

Cemetery explains medieval life and death

Around the churches, approximately 280 graves have been excavated, covering the full time the churches were in use.

The archaeologists have also established that the cemetery was in use after the last church building was gone, which may indicate that the place retained a special meaning for the people of Trondheim.

Although this was a Christian cemetery, many different burial practices, some not seen before in Trondheim, have been identified.

The placing of a stone in the mouth, stones placed on or close to the body, or of a wooden rod with the body – although strange to modern eyes – were likely to have been folkcustoms, done to help the deceased person on their journey to the afterlife.

The great number of child burials found reflects the high mortality rate of the time, but many, including infants, were laid to rest in carefully made coffins.