An article from Norwegian SciTech News at NTNU

Norwegian iron helped build Iron-Age Europe

Two thousand years ago, Norway produced iron in significant quantities. Much of it was exported both southward and northward from Trøndelag in central Norway.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Arne Espelund isn’t sure exactly when his interest in iron began, but the first time he tried making iron was as a student teacher with an eighth grade in 1977.

It didn’t work.

Making iron is not that easy, and something had gone awry for the eighth graders out in a bog near Trondheim. But they had a great experience and asked lots of questions.

It took a few years, but Espelund finally succeeded with another class at Skogn middle school in Levanger municipality.

“The students were thrilled,” says Espelund, who has long tried to bring this part of Norway’s history to life.

Espelund and his students adopted the iron-making method that Ole Evenstad had described in 1782. But this was by no means the first method devised.

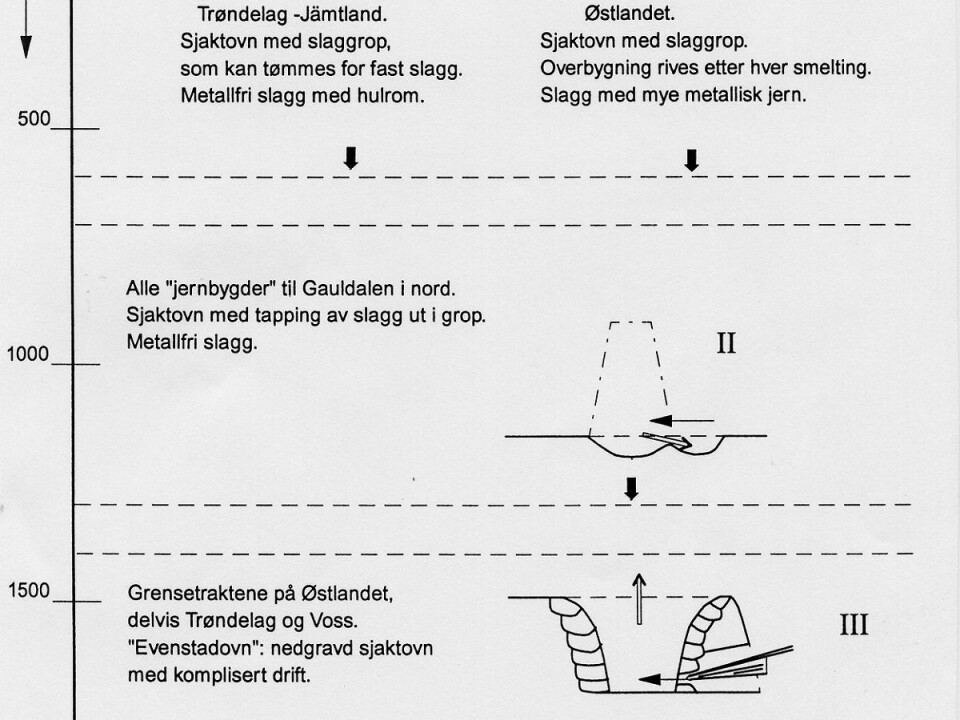

Two older methods using the bloomery technique have been used, but producing good iron by this “direct” method is an advanced process that requires the right temperature and oxygen supply, sometimes involving multiple steps.

Iron production started about 3500 years ago in Asia Minor. In Norway, people have been producing iron for at least 2300 years.

Interdisciplinary approach

Espelund is now an NTNU professor emeritus and a mining engineer, but he works in multiple disciplines. Studying iron production through the ages has been one of his main interests, although he is not a trained archaeologist.

Espelund finds that an interdisciplinary approach is essential to gain a holistic understanding of a subject. He does not hesitate to speak out when he disagrees with some of the archaeological work being carried out at a number of institutions, and is not shy about sharing his own assertions about other researchers’ results.

“Archaeology is descriptive,” says Espelund, and he thinks that many archaeologists are content to describe how something looks, but without going into depth on how it worked, and without putting the results into a natural scientific context.

But, he says, the context is important and can be figured out. For example, charcoal remnants used in the production process can be analysed using the C14 method to determine their age.

As a mining engineer, he readily uses chemical analysis to explain how our ancestors produced malleable and cast iron.

Finding slag heaps

Ore for iron production was gathered in marshes in the springtime, and smelting took place in autumn. After the iron was reduced, slag remained. Around 400 places in Trøndelag alone show traces of early iron production.

The conditions for iron production were ideal in Trøndelag and in Jämtland province in Sweden, with widespread access to both pine trees and ore.

“Today it’s the slag heaps we find first,” says Espelund. Slag didn’t have much value then, and it doesn’t now either, except as fill for road surfaces and as a tourist attraction.

Espelund has studied small pieces of iron slag from large slag heaps in Norway, Sweden, Iceland, Austria and Catalonia, and he has found similarities.

The slag heaps found all around Norway testify to significant production. A farm would use one to two kilos of iron per year until the Middle Ages — not much compared to the 450 kilos of iron we use annually now, but still impressive. Norway is ideal for examining this production.

“No other country has so many well-preserved furnaces from several periods,” Espelund says.

The reason is that Norway is a sparsely populated country, and many of the production sites were situated by marshes far from most people. In Denmark, on the other hand, most sites have been ploughed up and traces of iron production have disappeared.

Large scale production

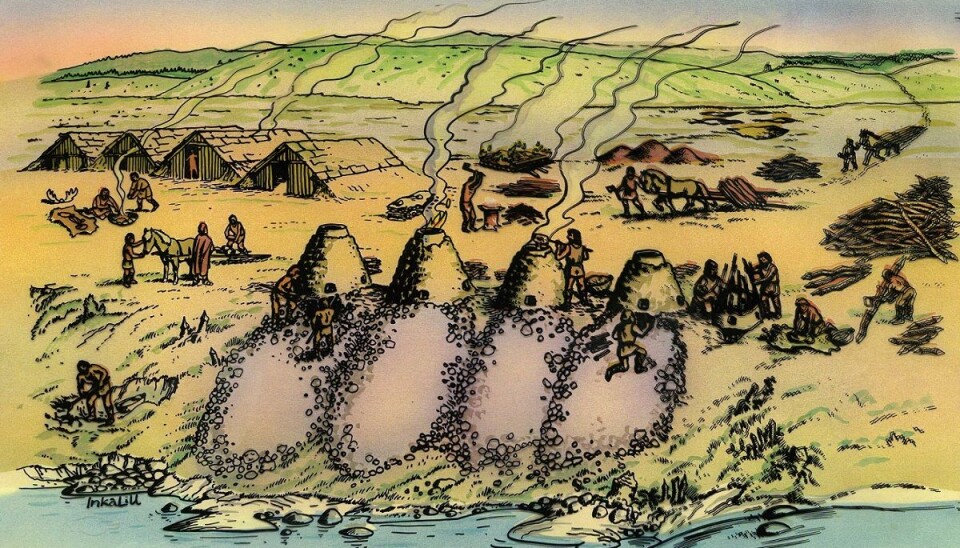

In 1982, Espelund was part of the research team that discovered the 2000-year-old iron production facility at Heglesvollen in Levanger in Nord-Trøndelag. Here they found four ovens and dug out one of them.

The researchers found a total of 96 tonnes of slag, which was spread equally between the four furnaces. This suggests that the furnaces operated simultaneously, but in different stages of the production process.

It is quite common to find four ovens beside each other. For some reason, not yet understood, there is always water in front of the ovens.

“We estimate that teams of about 10 people worked together,” says Espelund. “We are talking about a well-planned production process and an industrial enterprise with periodic, batch operation of all the furnaces.”

Nothing indicates that any religious or other rituals were part of the process, or links it to women or children.

The evidence points to a rational, industrial production of iron, with the focus being on obtaining the best possible metal for tools and weapons through hard work.

The best iron

Those involved in iron making must have been highly specialized workers who were taken out of food production and other useful work to produce iron in the summer months. The iron was important, and it was also of high quality.

“A lot of this iron contains about 0.2 percent carbon. That’s on par with the best iron a blacksmith can get,” says Espelund.

Iron with a low carbon content is malleable, without becoming brittle. However, various kinds of iron were produced depending on the type of application it was used for. How did these people of yore manage to make such good iron? Espelund has studied this for half of his life, but so far he doesn’t quite know how they pulled it off. No one knows for sure.

Espelund believes that this iron making method can be compared with the technique used in the Roman Empire — and this in a region with no written language or imposing buildings.

This first technology was in use in Norway for about 900 years, from around 300 BCE to 600 CE. The production was so high that some 40 tonnes of iron per year were produced in Trøndelag around the year 200 CE. Much of the iron was probably exported south to the European continent, where phosphorus-free welding steel was sought after.

Around the year 600 CE the entire production stopped and lay fallow for several years.

Crash

“I think the market collapsed,” says Espelund. The crash coincides with pestilence and famine in Europe.

Traditional knowledge can disappear after only a few generations, and the art of iron making was transferred through doing it, not through the written word. Soon Norwegians no longer knew how iron was made.

“They had to start all over again,” says Espelund.

The ancient methods of production disappeared, but a new one was developed, until the next crash occurred with the Black Death that swept through Europe in the mid-1300s. The same story repeated itself, and yet another new production method had to be invented afterwards.

Espelund used this last production method in his experiments with schoolchildren in the 1970s.

Where did iron making originate?

People are not exactly queuing up to take over his research field, so Espelund is thankfully still going strong. But chemist Tore Haug-Warberg has taken great interest in the field.

At 85, Espelund is now quite grown up, and these days he is cleaning out his office at NTNU, after many years as a professor emeritus.

He has financed much of his research himself, partly by self-publishing books and working many hours beyond the call of duty.

It seems that the technology for the oldest iron production in Norway originally came from the east, perhaps from Georgia. Espelund has come across publications on iron production there, which shows that the furnaces resemble ones in Norway. The chemical analysis of slag from Georgia does not show any correlation with samples from Norway, but the furnaces with slag pits are apparently quite similar.

The Georgian furnaces are about 500 years older than the Norwegian ones. Maybe the technology came to Scandinavia from the Middle East.

Espelund hopes to travel to Georgia to find professional contacts, and no doubt more results will be forthcoming. But we may never know the whole truth about early iron production in Norway.

Arne Espelund has written several books, including “The evidence and the secrets of ancient bloomery ironmaking in Norway,” which can be useful for those who want to know more.