An article from University of Oslo

Life changes with electricity

Over the next fifteen years, 1.3 billion people will get access to electricity for the first time. How will this affect the societies concerned?

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Electricity makes marvelous things happen and its capacity to produce bright, radiant light makes an especially striking impression when it arrives. Electricity’s introduction thus tends to be associated with progress and modernity.

This was the case in 1879 when Thomas Edison displayed an incandescent lamp for the first time in Menlo Park in New Jersey and seven years later when the sultan’s palaces in Zanzibar Town were lit.

Energy has traditionally been studied by researchers within the fields of natural sciences and economy. Anthropologists who have engaged with energy and society have mainly concerned themselves with fossil fuels and the role of these in global politics—specifically, around issues of climate change, energy security, and oil depletion. The societal impact of introducing electricity and the enormous transformation going on in the South in recent years have received little attention.

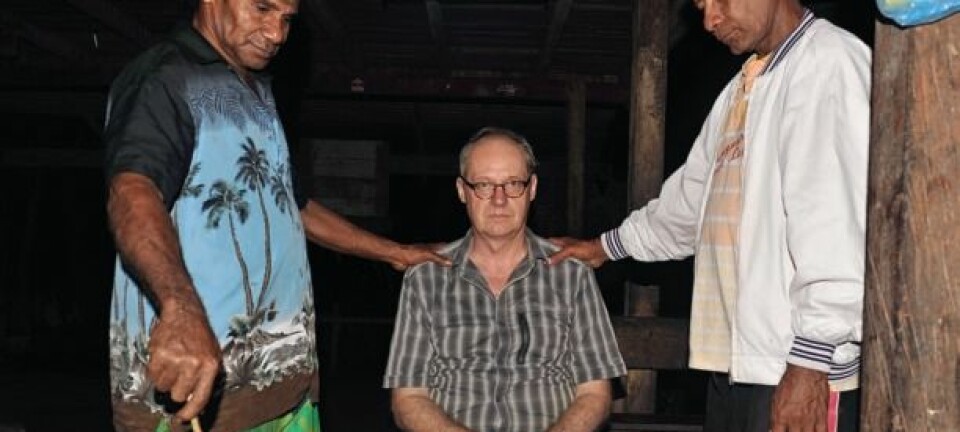

Tanja Winther and Harold Wilhite at the Center for Development and Environment have recently published an article where they use their fieldwork from Kenya and Tanzania to show how electricity’s arrival in new places affects community and household practices, social relations, local economy and power relations.

When I have seen what the president looks like, I will also feel as being part of Kenya

Because electricity’s infrastructures are physically heavy, costly, and enduring, their configuration continues to remind observers of the power of the State that provides them.

This affects the state-citizen relationship in crucial ways. The initial recipients of the electricity are usually those institutions with political and social power. In Uroa electricity strengthened the standing of Islam, the villagers’ religious practices, and their affiliation with global Islamic networks.

Amplifiers and speakers ensured that people would wake up for the 5:00 a.m. call for prayers. Tape recorders and television programs conveyed the messages of grand religious leaders, and electricity-driven water pumps ensured access to clean water. Overall, the bright light radiating from the village mosques at night testified to the purity and omnipresent power of Islam in this place.

The productive interests of women were not taken into account during electrification: female institutions in the village such as the mill and kindergarten were never electrified, reflecting women’s subordinated status in Uroa.

– This shows that the coming of electricity strengthens the social power of existing institutions rather than changing them.

The arrival of electric light can change the meaning of place. In Uroa people began to speak of their village as a town on the day the streetlights were turned on, thus elevating the status of their electrified place vis-à-vis neighbors who continued to live in darkness.

The sense of centrality brought on by electricity is further intensified by people’s newfound access to mass media and communication, enabled through such devices as televisions and mobile phones.

– Electricity literally connects various localities in new ways and modifies perceptions of belonging. An older man in Ikisaya village in Kenya expressed his expectations that electricity and television would bring with them a feeling of inclusion and national identity: “When I have seen what the President looks like, I will also feel as being part of Kenya”

Men came home after work

In Zanzibar the researchers also saw a shift in household practices, everyday practices and social relations after the electrification..

The presence of the television prompted men to come home in the evening instead of spending time outside the house with friends.

Living rooms were restructured to allow for gender-mixed settings of television viewing while still keeping a proper moral order. Due to the prestige of the modern couple hosting television-viewing time, the gender hierarchy was temporarily challenged, elevating the female host’s social position above that of male guests.

Before electrification, male status had been evaluated mainly based on the number of children and wives, but now a man might be ridiculed if he married a second or third wife without being able to provide the first wife with access to electricity. Husbands are expected to treat all wives equally, and the cost of providing them with televisions is actually preventing some husbands from marrying several wives.

– These glimpses of electrification’s multiple impacts in one site underscore the importance for ethnography and anthropological theory to take more seriously the place of electricity in maintaining and challenging social orders, an effect that tends to be overlooked in current assessments of electrification projects in the global South, says Harold Wilhite.

Electricity’s materiality is fast and electric light can be summoned with a switch. Despite this high speed, the advent of high-voltage electricity systems also means that the location of the production of electricity and the pollution it generates is often be geographically distant from the points of consumption.

The electricity in Zanzibar was imported from the mainland of Tanzania through submarine cables, and people were not concerned with its sources.

In contrast, people in Norway and France are highly concerned about their countries’ main sources of production - hydropower and nuclear, respectively. This awareness influences people’ consumption of energy.

In Norway, electricity is perceived to be cheap, safe, and clean, and is associated with the mountain reservoirs and rivers providing the energy, which are regarded as common resources. In France, electricity is perceived to be risky, both economically and in a physical sense due to the nuclear materials and wastes involved in production.

The electricity time squeeze

Electric light brings with it a fundamental impact on the distinction between day and night. Instead of depending on the natural cycles of sun and moon, daily activities can be performed also during evenings. In this sense electricity enables people to overcome “natural” limitations and to experiment with new practices.

In Uroa this had the effect of speeding up the pace of life to the extent that many people felt that they had too little time. Many referred to this effect when telling us about the changes brought by electric light and television, complaining that they now had “no time” (hamna time).

Moreover, outdoor space was regarded as safer to humans because spirits were thought to prefer darkness and tended to withdraw from (en)lightened villages. With electric light, villagers reclaimed outdoor spaces at night that were formerly the domain of occult forces.

Winther and Wilhite concluded that there is a general need to bring cultural practices, material agency, and political economy to theories of development and electrification.

This would imply, as the case of Uroa illustrates, paying close attention to instances of electrification and how these impact both the social construction of needs and the mediation of social relations within the household and beyond.

-------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no