An article from Norwegian SciTech News at NTNU

Students rebuild an orphanage after Typhoon Yolanda

Four Norwegian architecture students spent their autumn semester working on rebuilding Streetlight, an orphanage in the Philippines that was destroyed by a typhoon before Christmas last year.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

A little over a year ago, the city of Tacloban in the Philippines was ravaged by Typhoon Yolanda. The typhoon created a tidal wave that slammed into the land, turning a whole settlement to kindling.

During the typhoon, children and adults from a student centre and orphanage called Streetlight held onto the roof of the organization’s main building, which miraculously was not swept into the ocean by winds and waves that crashed into the area around Tacloban.

Everyone associated with Streetlight survived, but the buildings were all destroyed by the storm.

Suddenly Erlend Johansen, a Norwegian who established the orphanage and study center for street children, had dozens of homeless children on his hands – and nowhere to offer them shelter.

A collective effort

The typhoon and its disastrous results were a real wake-up call to the Norwegian people, and donations flooded in to help with a rebuilding project.

Now, a year after the typhoon, architect Alexander Furunes is helping to rebuild Streetlight. He is doing this via an architecture organization called WORKSHOP, which he runs with two colleagues.

Together with his colleagues, Furunes built the first centre in 2010, the one that was destroyed by the typhoon.

Furunes has four architecture students with him who are spending their fourth and fifth semesters working in the field. Way out in the field. Furunes is the field supervisor for the students, and Hans Skotte is the academic supervisor back home at NTNU in Norway.

Growing by 1000 percent

Children in the Streetlight program are currently staying in temporary houses that are built in the same area as the old orphanage and school. But a new permanent centre is being built further inland, in Tagpuro, which is much more protected from extreme weather.

Many of Tacloban’s citizens are also moving into new houses in Tagpuro— over a short period time, the town will grow from about 200 families to 2000 families. This will bring new challenges, new problems to be solved. How will the new residents support themselves? Most of the inhabitants of Tacloban were fishermen, but Tagpuro doesn’t have space or resources for so many fisherfolk.

How will so many people be transported? How and when will the roads be expanded? Where and how should the new houses be built?

“There’s a lot of questions to answer in this project,” says Furunes.

The architecture students have been involved in helping to prepare new areas for construction, and to make the moving process as easy as possible.

Creating a meeting place

Incorrect information — or simply lack of information — is one of the main problems throughout this process. So the students have concentrated on conveying information to everyone who is affected by the situation, both inhabitants of Tagpuro and those who are moving there.

To be able to effectively get new information out to everyone who needs to know, the students use a bus stop in the centre of town as a sort of hub. Why a bus stop? Because bus is the most important method of transport in the area, and the bus stop is where people meet.

The problem with moving families from one place to another is that they are moving away from their livelihoods. If they are not able to find new work in their new neighbourhood, which has been the case for many families, the parents will have to commute to and from Tagpuro to their previous home of Tacloban, where there is work to be found. People commute by bus, which is why the bus stop is an important meeting place.

“The students are also preparing new ground for a large amount of construction, and for moving a lot of people,” says Furunes.

Making new maps

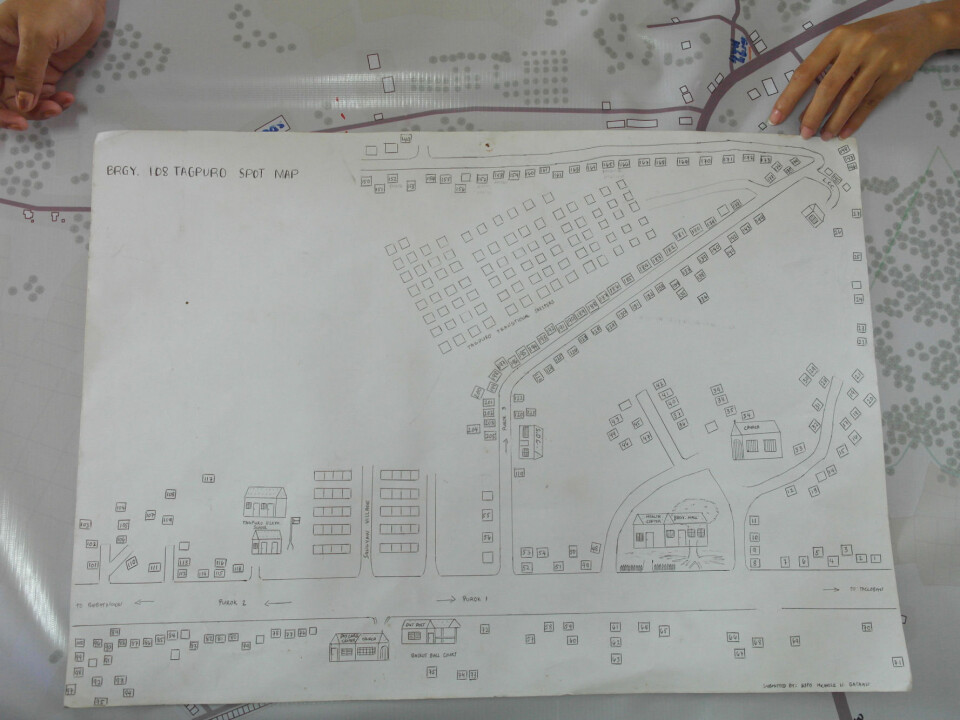

One challenge that many students have encountered — and have solved — is that there are no good maps of the area where they are working. Therefore, it has been very important to make visually clear maps that give the inhabitants a good idea of the changes that they are making.

Hand-drawn maps of the area are all that were available previously, and these don’t include the new housing. The maps that the students made have given the inhabitants an idea of the scope of the new housing project, and these maps can simultaneously be used as a tool to create new ties between families in the new area.

The bus stop is a natural place to hang up the new maps, so that inhabitants can discuss the changes that are being made.

Shielded from the rain and sun

The coast of the Philippines is often exposed to sudden heavy rain and strong sun. For this reason, it is important to be able to shelter underneath a roof, when waiting for the bus, or discussing changes to the area.

“When the bus stop was presented, people said we needed include a watch tower as well, so now we are building a two story building for the local guards, with their help,” explains architecture student Kristin Solhaug Næss.

“It’s a very important collaboration that will hopefully be a hub and meeting place for the area’s residents.”

A valuable field experience

The architecture programme at NTNU puts a strong focus on making sure that students have the opportunity to work in the field, with practical tasks and actual buildings, not just sketching architecture on the drawing board and in models. The four students who have spent their autumn semester in the Philippines have now had plenty of field experience.

“We’re discovering that it takes time to understand areas and cultures, and the processes that we’re working with. Interaction with the environment is key, and the architects aren’t the bosses who sit on a pedestal and decide how everything should be. You need to consider and include the people who are going to use these buildings,” say John Haddal Mørk, Kristin Solhaug Næss, Sebastian Østlie and Anders Gunleiksrud together.

“We could have built the same houses somewhere completely different, but we certainly would not have learned as much if we didn’t get to be in these surroundings and meet all of the challenges we’ve come up against first hand,” says Østlie.

“We’ve learned a lot about what architects can do — and what limitations there are,” says Næss.

After the typhoon destroyed Tacloban, Streetlight was temporarily rebuilt using recycled materials.

The permanent rebuilding of the children’s home will be in Tagpuro, a town further inland where the weather is calmer. Here, the children’s home, school, infirmary and office buildings will be built.

“We’re also building a park with infrastructure for the locals,” project leader Furunes explains.

“The idea is that this will be an area where both current residents and newcomers can meet and build a community.”

While building both the new park and buildings for the school, the same methods were used as the previous construction period, in 2010: involving the locals. Doing this creates a sense of ownership to the project, and it also brings the local’s knowledge about the area into the process, both about materials and building processes, as wells as about space needs and room placement.

The applications have been sent in, and construction is planned to start in February.