This article was produced and financed by Institute of Marine Research

Acidic ocean water makes sea snails smaller

Sea snails prefer to be smaller when they are stressed by high CO2 levels.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

New findings explain why marine species that survived previous mass extinction events were much smaller – a phenomenon known as the ‘Lilliput effect’.

Sea snails respond with stunted growth when they are exposed to the high levels of CO2 we can expect in the future oceans.

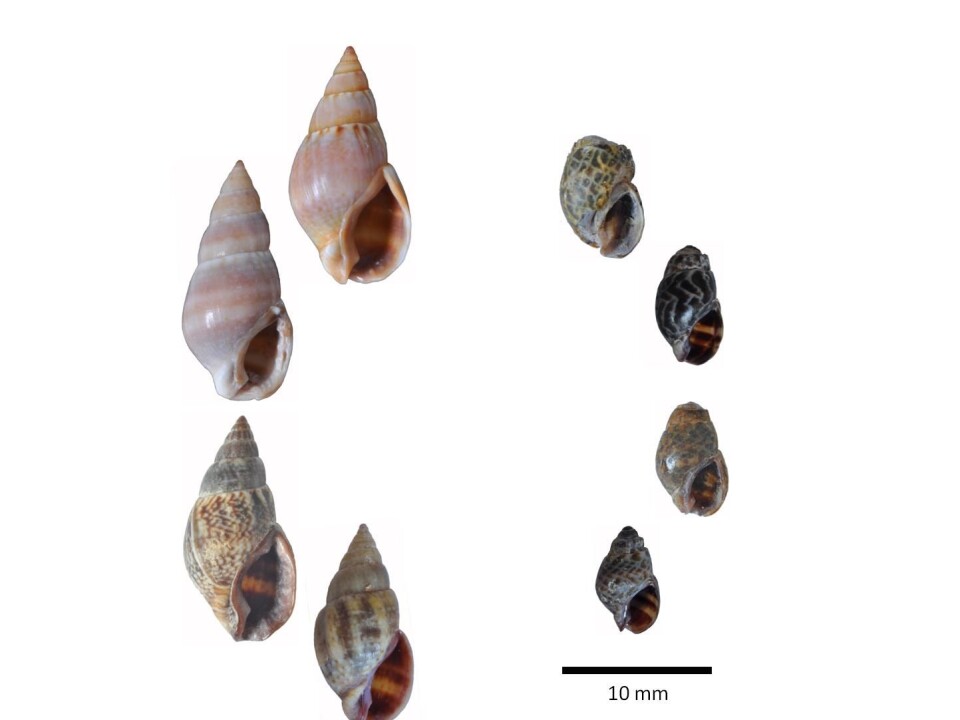

A team of marine scientists and paleontologists from ten institutions in Norway, Italy, Monaco, New Caledonia and the UK has studied how sea snails cope in more acidic conditions. Two species of snails growing at shallow water CO2 seeps were compared to those found in normal pH conditions.

Adapted over many generations

The shells from high CO2 seawater were about a third smaller than the snails from the normal environment.

The finding, recently published in Nature Climate Change, confirms that stunted growth can be an adaptive response to ocean acidification, enabling some sea creatures to survive high carbon dioxide levels, both in the future and during past mass extinctions.

The study also confirms the theory that the snails had adapted to the conditions over many generations.

Being small is an advantage

Samuel Rastrick from the Institute of Marine Research was responsible for determining the animals’ metabolic rates in the study.

"The metabolism is a decisive survival factor when the environment changes," he says.

"Metabolic rates change with body size. This means that smaller animals can maintain comparatively higher costs of survival per gram of tissue whilst reducing their total need of energy. This gives smaller animals the advantage."

More acid water affects the calcification process that ensures snails and other marine species healthy shells. The study shows that the metabolic changes allowed the animals to maintain calcification and to partially repair shell dissolution.

Warns about the impacts

Examinations of the fossil record also show that mass extinctions and dwarfing of marine species are repeatedly associated with episodes of past elevated oceanic CO2. It is likely that similar changes will increasingly affect modern marine ecosystems, especially as the current rate of ocean acidification and warming is so rapid.

The change in seawater chemistry is already affecting marine organisms, ecosystems and the services they provide. In a joint press release the team of scientists warns about the impact that continuing ocean acidification could have on marine ecosystems – unless the rate of carbon dioxide emissions is drastically slowed.

"If animals become smaller to survive elevated CO2 levels this could have an obvious effect on the aquaculture and biomass production of some species," says Rastrick.