THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY The Norwegian School of Sport Sciences - read more

Impossible to calculate the avoidance of injuries

Everyone wants to avoid sports injuries, but drawing up a training programme to achieve this is a myth. The solution, however, is quite simple

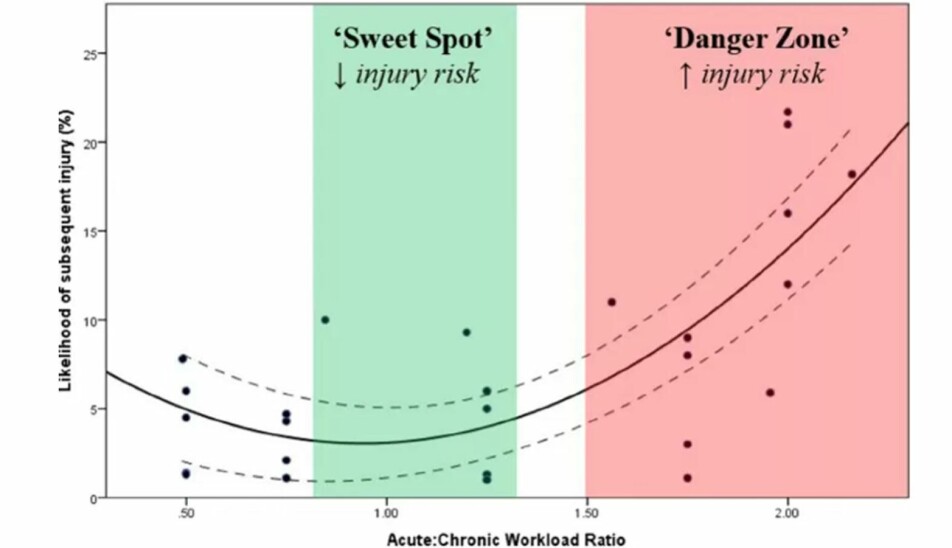

It was established as a truth and applied diligently around the world: if you want to avoid injuries, you can develop your training week by week in accordance with a fixed "percentage add-on".

"Bring on fixed add-ons"

According to the Australian behind this "revolution" in sports medicine, we can all calculate the speed at which we can increase our training load while simultaneously being sure of avoiding overload and injuries. This principle works for most sports and the results would quite simply become manifest.

Unfortunately it turned out that this was a bit too easy.

- Torstein Dalen-Lorentsen is a Research Fellow at The Centre for Sports Trauma Research at the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences (NIH).

- On 16 December he will defending his doctoral thesis at the NIH: “Training load and health problems in football – more complex than previously thought?”

500 tested, no correlation

The theory was great, but it lacked a proper research basis, so in 2017 Torstein Dalen-Lorentsen at the NIH set out to fix that. He wanted to support the theory. Consequently he rigged up an experiment involving 500 participants from the whole country, comprising 15-19-year-old junior elite football players. His aim was to establish how clear the connection actually is between increasing load and injuries.

However, his project quickly fell apart because a lot of things failed to add up.

"The first thing we saw was that there were indeed more injuries among those who suddenly increased their training, compared to those who adopted a slower approach. However: “was the urgency the cause of the injuries?” he asks. He says that there was a correlation between increased training load and injuries, but [ no coherence - in other words: it was impossible to determine injury risks on the basis of training load.

Too complex

One of the things that quickly became apparent was that individual conditions have a lot to say about how vulnerable we are:

"Genes, age, type of musculature, body composition, basic training, previous injuries – even one’s position on the pitch, muscle type and mental state all have an impact on individual safety," explains Torstein Dalen-Lorentsen. "I would love to be able to provide trainers with a simple tool for helping both fitness enthusiasts and top athletes, but unfortunately that’s not possible.”

“You still have to think about and adapt exercises and training to suit the individual. A one-size-fits-all approach doesn't work.”

However...?

Even though this theory was not really good enough, Mr. Dahlen-Lorentsen nevertheless wanted to check whether or not the principle involved in this theory was in any way valid, i.e. whether or not a systematic, controlled load increase could prevent injuries. So he allowed half the youngsters to increase their training as planned by NN, while the remainder [engaged in normal/regular training - I didn't quite grasp this].

"To put it simply, this had no effect on prevention.”

However, he believes that there is a lot to say for the concept, i.e. that you can prevent injuries by engaging in steady progression.

Consequently he also asked the young people what they thought about introducing injury prevention measures – and what makes this so difficult in practice. Because experience shows that athletes rarely use special exercises – even though they know that they will produce good results.

Groups and performance

He found two keys: who you get to join you - and whether or not an exercise improves your performance.

"In practice, the latter means that when implementing preventive measures in team sports, you need to focus just as much on what it means for your performance as on actual prevention.

It is therefore important to document how important an exercise is in order to improve your performance. And we’re not just talking about acute injuries, but also about what you can avoid having to struggle with in the long term. Injuries accumulate.

He also discovered that you need to include not just the players themselves, but also their trainers. "The young people were interested in this, while the trainers talked about how important it was for the young people to join in. They are involved in a sort of symbiotic process.”

Dangerous intentions

According to Mr. Dalen-Lorentsen, an important step forward would be to find out which training loads and programmes work best for different sports and ideally adapt their use to each individual player. On that basis it might be possible to implement a gradual increase in training loads.

"But getting it right by using one simple calculation wouldn’t work?"

"As soon as it becomes a fixed model, it stops working."

According to Torstein Dalen-Lorentsen, the study boils down to one simple lesson – in addition to the fact that the whole milieu would have to be included and one would have to place emphasis on how prevention would affect performance:

"You have to forget about any fancy stuff, comply with old principles and be careful, at least if Syou want to keep fit and healthy," he says. And he thinks that this might be particularly important now in the run-up to Christmas: “New Year's resolutions are dangerous. If you start too quickly, things can quickly go wrong. And that's not very motivating.”

PS

He is still hoping to find a model that works. In a new PhD which he has recently started, his aim is to "crush" all the figures about injuries and training loads and hopefully get a bit deeper into the statistics.

See more content from The Norwegian School of Sport Sciences:

-

Inactivity can leave lasting marks on your muscles

-

Football expert wants to change how people watch football at home

-

Kristine suffered permanent brain damage at 22: "Life can still be good even if you don’t fully recover"

-

Para sports: "The sports community was my absolute saving grace"

-

Cancer survivor Monica trained for five months: The results are remarkable

-

What you should know about the syndrome affecting many young athletes