This article was produced and financed by University of Stavanger - read more

A number of Norwegians voluntarily joined the Confederate Army during the American Civil War. They fought to maintain slavery.

This and much more was discovered by Gunnar Nerheim when he dived deep into the history of the first Norwegians in Texas.

“They settled right in the middle of Native American territory and shortly afterwards, the Norwegians and the Comanche nation were at war with each other”, says historian Gunnar Nerheim.

His new book has all the ingredients for a good old-fashioned cowboy story. Here he explains why so many emigrants from the Norwegian counties of Rogaland, Agder and Hedmark became settlers in Texas. Not only does he contribute to the history of the life emigrants actually lived, he also reveals the narratives and destinies of the individuals who settled in Texas in the 19th century.

“This is the story of crop failures and malaria, Norwegian attitudes towards slavery and how cheap labour was recruited from back home”, Nerheim summarises.

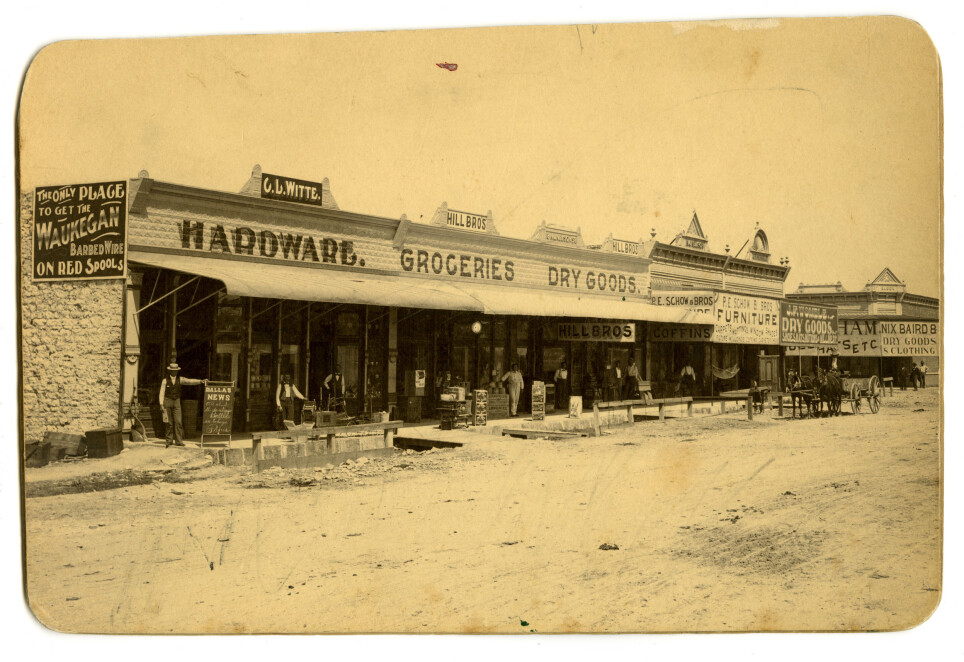

A Norwegian college in Bosque County

We rewind nine years. It was then that Nerheim was introduced to the “Norwegian” Clifton College in Bosque County, Texas.

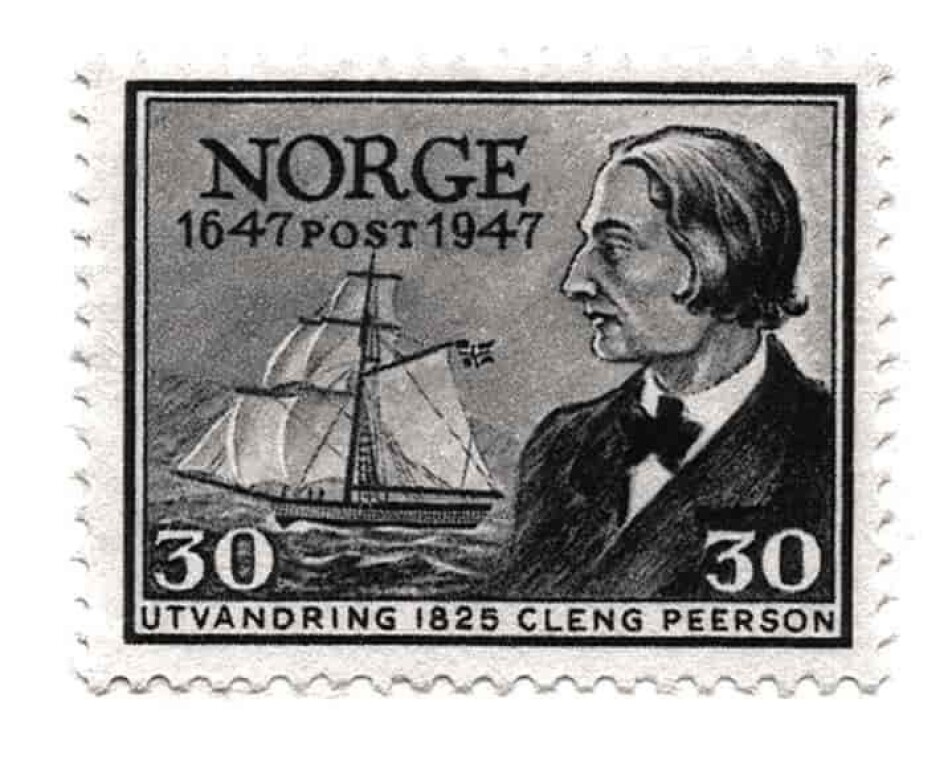

The story of Cleng Peerson, the father of Norwegian immigration, is well-known. The final ten years of his life, he lived in Texas, and in 2011, descendants of Norwegian emigrants to Texas began to make plans for a Cleng Peerson centre in Clifton. Nerheim was attached to this project, and there, he discovered the archive at the Bosque Museum.

“I scanned until the photocopier overheated and the hourglass ran out. Gradually, as I read the documents, I realised that I had found material that told the story not just of Cleng Peerson but the entire milieu of Norwegian emigration to Texas”, he says.

The book follows the tiny Norwegian colony in Texas from 1845 to the early 20th century, where virtually everyone can be traced back to the original emigrant families from Rogaland, Agder and Hedmark.

In the autumn of 1845, Johan Reinert Reiersen established the first Norwegian colony in Texas. This was the start of one of the three chain migrations that Nerheim distinguishes in the book.

“Reiersen did not want to go to Wisconsin or Missouri, where the winters were just as cold as they were back home in Norway. The sun and the warmth was more tempting, and he had thought of going to Brazil or California before he ended up in Texas”, says Nerheim.

The climate was better and the soil was more suitable, but in the late summer, malaria arrived and many died.

In the autumn of 1850 Cleng Peerson brought a small group of Norwegians from Fox River to Texas. This marked the beginning of the Peerson migration chain to Texas. Central people who followed the Peerson chain settled in Bosque County from 1854 onwards.

From 1870, this was the leading Norwegian colony in Texas, and the Norwegians fared well for the most part. The Norwegian college, Norwegian church and large farms became important keywords.

God spoke Norwegian

In the book, Nerheim has confirmed how important the three migration chains were in the establishment of the Norwegian colony in Texas.

“New Norwegian settlers constantly took over the Norwegian-American settlements from their Norwegian ancestors as they would have done back home”, he says.

“This helped them hold onto their Norwegian culture for a very long time. Many of them maintained the language, and as late as 1906, young children began school without being able to speak a word of English, despite their families having lived in Texas for many generations”, Nerheim points out.

He believes that the church was an important factor in this.

“God spoke Norwegian! Young people could not be confirmed without being able to speak Norwegian, so they went to summer schools in order to learn Luther’s Small Catechism – in Norwegian”, he says.

A lad from Hedmark cheaper than a slave

Another element that has been little known before Nerheim delved into the sources he found, are the Norwegians’ attitudes towards slavery, and how many Norwegians fought in the American Civil War.

“It was cheaper to write home and persuade a lad from Hedmark to come over to help out on the farm, in exchange for getting the ticket paid, than it was to buy slaves”, Nerheim states.

He points out the difference between the Norwegians further east in Texas and those who settled in the west. The material Nerheim has found suggests that the majority of the Norwegians were against slavery. In Bosque County, there were relatively few slaves, and none of the Norwegian immigrants there owned slaves.

“Many Norwegians from this area were therefore forced to join the Civil War eventually as the war progressed, whilst others enlisted due to the social pressure to show patriotism”, says Nerheim.

It has long been an opinion that all Norwegians in the United States felt disgusted with slavery, but Nerheim's book shows that this was not necessarily so.

Entered the Civil War with enthusiasm

Other Norwegians, especially in the east, broadly accepted the tradition of slavery, social practices and the expectations within the larger society around them, once they had settled in the south.

In eastern Texas, the economy and daily life were shaped by cotton production and slavery, and individuals within the Norwegian immigrant community bought slaves.

“There were differences. The sources show that there were also some Norwegians who freely volunteered with the confederate side in the Civil War, relatively early on in the war, and through this, fought to maintain slavery”, says Nerheim.

Within the book, he describes how the Norwegians experienced life in the Southern Army. During the Civil War, disease and plague took at least as many lives as the acts of war, and the Norwegians did not escape this. At times, the Confederate Army had little food and ammunition, and had to endure long daily marches, but during other periods it was easier, and they had the time to take part in horse racing.

Some of the soldiers sent letters home, and through these we can form an image of how some of the Norwegian immigrants experienced the American Civil War from the inside.

“Reflections of the war emerge both from the actual words written and between the lines”, the historian believes.

Many of the letters were collected in a private archive that has since been donated to St. Olaf's College in Minnesota. These, along with other letters found at the University of Austin and information within databases of the Civil War, have given Nerheim the ability to present a good image concerning how many Norwegians joined the war and how they experienced it.

“It has previously not been known how many Norwegians actually joined the war on the side of the confederates, but surprisingly, many of the Norwegians in Texas did just that, both voluntarily and involuntarily”, Nerheim concludes.

Fewer immigrants by the end of the 19th century

Towards the end of the 19th century, the price of the little amount that was given by the soil rose, and the dream of one’s own farm became more difficult for newly settled Norwegians to achieve. However, Norwegian immigration to the United States dropped sharply when the international economic crisis took place in 1873.

“More and more people wanted to own their own land all the time. Farmers with little or no capital could not afford to buy land and had to settle for renting other people’s land”, explains Nerheim.

Nerheim believes that the book fills a gap within migration literature.

“Very little has been written about the Norwegian settlers in Texas previously, and never has the actual life they lived been so fully described. The book builds on what has already been found from published material, but more importantly builds on new and broader source materials than what has previously been utilised”, he says.

The historian has been in Texas doing source work on several occasions in order to complete the book, and the text appears in both Norwegian and English.

“After retiring in 2016, this has been my main project. The English version is published by Texas A&M University Press and will soon be launched out there”, concludes Gunnar Nerheim.

References:

Gunnar Nerheim, I hjertet av Texas. Den ukjente historien om Cleng Peerson og norske immigranter i Texas. Fagbokforlaget, 2020.———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no