THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology - read more

How can towns be protected from lava flows?

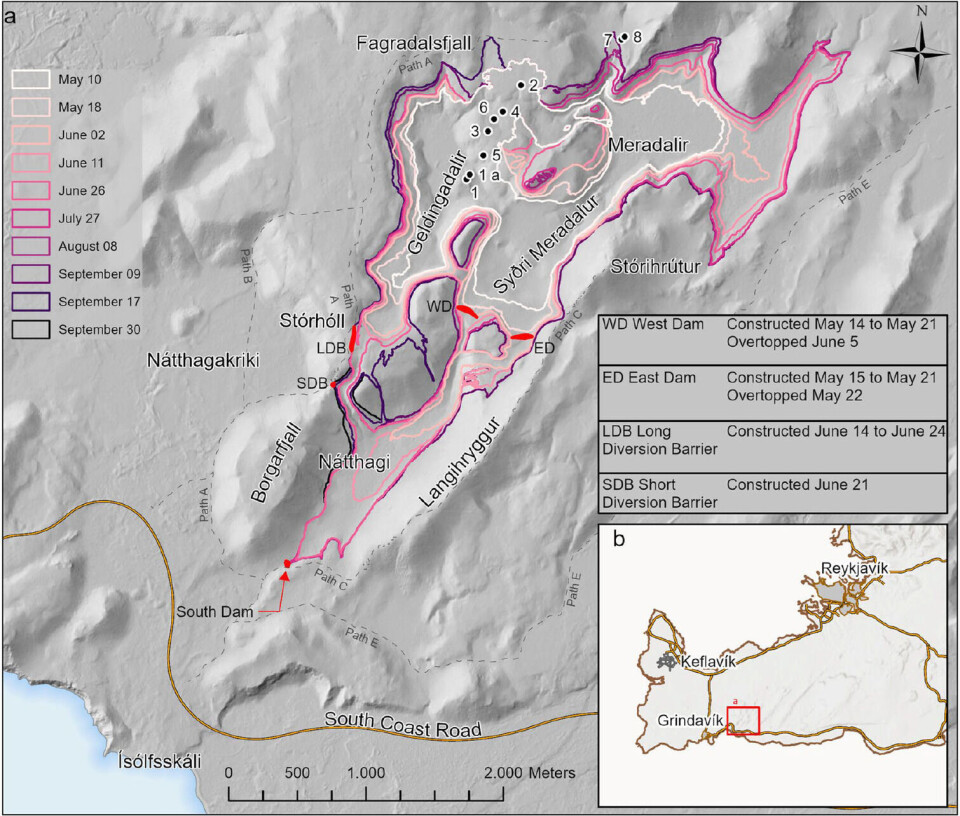

In March 2021, the Fagradalsfjall volcano in Iceland came to life. While the eruption was ongoing, large-scale field experiments were conducted to build defensive earthen barriers aimed at slowing down the molten lava flow.

Building defensive barriers to slow the lava flowing from craters and fissures in the Earth’s crust was often a race against time.

The excavator and bulldozer operators had to work around the clock. They shovelled dirt and rocks to build dams and barriers while the glowing hot lava from the eruption crept ever closer.

Delayed lava flow for 16 days

The speed of lava flows is determined by the viscosity of the lava and how steep the terrain is.

When an eruption threatens civil society and infrastructure, the most important goal is to gain as much time as possible by delaying and potentially diverting the lava flows.

NTNU professor Fjola Gudrun Sigtryggsdottir’s field experiment in Fagradalsfjall in 2021 showed that the dams delayed the lava flow by up to 16 days. They also succeeded in building effective barriers that diverted the glowing stream of lava in a safe direction.

The lessons learned would prove useful when the small town of Grindavík found itself in the danger zone of a new volcanic eruption just a couple of years later.

Lava flow can be controlled

“The main lesson we learned from that field experiment was that it's possible to control lava flows – to some extent. And it's certainly worth trying when it comes to protecting civil society and critical infrastructure,” says Sigtryggsdottir, who closely followed the field experiment.

She is a researcher at NTNU’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, and an expert on safety in relation to embankment dams, infrastructure, and geohazards.

Over 40,000 earthquakes

“The project also showed what it's like to work in close proximity to an active volcano and flowing lava. We confirmed that it's possible to work under such challenging conditions, and that the risks can be minimised if we take specific safety measures,” says Sigtryggsdottir.

In the period before the eruption, Icelandic authorities recorded more than 40,000 earthquakes. When the Fagradalsfjall volcano came to life, Sigtryggsdottir was already in Iceland and involved in the lava control project.

The Icelandic Department of Civil Protection and Emergency Management already had a working group in action. They were tasked with mapping areas threatened by lava flows and proposing measures to protect critical infrastructure.

Sigtryggsdottir participated in the group along with engineers from the consulting firms Verkis and Efla, as well as researchers from the University of Iceland and the Icelandic Meteorological Office.

Became a tourist destination during the pandemic

“The eruption had not started when the working group was established. At that time, it wasn't even certain that there would be an eruption,” says Sigtryggsdottir.

But the eruption did come. A fissure opened in Geldingardalir valley on the evening of March 19, 2021. The Covid-19 pandemic was still ongoing.

Lava flowed across the landscape, and people flocked to witness the volcanic forces being unleashed.

Major road under threat

Fagradalsfjall is located on the Reykjanes Peninsula, eight to ten kilometres from the nearest settlement in Grindavík.

At first, neither civil society nor infrastructure were at risk. However, after a few weeks, the red-hot lava had moved through yet another valley and began threatening an important national road.

At that point, the Department of Civil Protection and Emergency Management decided to build barriers to delay or divert the lava flow away from the road.

“At that moment, our work was effectively transformed into a large-scale field experiment,” says Sigtryggsdottir.

Tested different barriers

The Fagradalsfjall volcano continued erupting for six months before settling down in September 2021.

This gave the researchers time and opportunity to test different construction methods and barrier types in an area that was not as directly at risk of infrastructure damage, such as Grindavík and the Blue Lagoon.

This was the first eruption in the area in 800 years. Occasionally, the lava started flowing unexpectedly into new areas.

When that happened, they were able to test the difference in strength between the massive main barriers and temporary measures, where bulldozers piled up embankments of earth, sand, and stone as the red-hot lava crept ever closer.

Built an 8-metre-high embankment

Protecting civil society and infrastructure from volcanic eruptions is about gaining as much time as possible by delaying or diverting the lava flows.

In total, three embankment dams of earth and stone were built during the field experiment. The highest was 8 metres tall. Two 300 metres and 35 metres long barriers were also constructed to guide the lava in a different direction.

The researchers have summarised their experiences and the lessons learned in a scientific article recently published in the Bulletin of Volcanalogy.

When the Fagradalsfjall volcano came to life in the spring of 2021, it had been nearly 800 years since the last eruption on the Reykjanes Peninsula. (Video: Fjola Gudrun Sigtryggsdottir)

Created a guide for the authorities

Sigtryggsdottir has also created a barrier construction guide for the Icelandic authorities.

It is based on research literature on lava control and her own area of expertise: embankment dam safety.

The document describes how different barriers can be built using locally available materials and how they should be positioned to withstand and control lava flows.

Used to protect Grindavík

The experience from the field experiment proved useful when the authorities later built a lava barrier to protect Grindavík and a geothermal power plant on the outskirts of the town.

The work began before the first eruption in December 2023 and continued through the winter of 2024.

Sigtryggsdottir was only involved in the phase before and during the first eruption in 2021.

“But my colleagues have all been actively involved in the barriers built for the later eruption in Grindavík and were able to apply the experience from our study to that work,” she says.

Houses would have been buried

If authorities had not followed Sigtryggsdottir’s recommendations, things might have turned out differently in Grindavík in 2023–2024.

“If the barriers hadn't been built, several of the houses there would now be under lava,” she says.

Sigtryggsdottir adds that each volcanic eruption provides newinsights and new experience, which means Iceland’s officials will be better prepared the next time something happens.

New volcanic activity

In the spring of 2025, significant volcanic activity is once again taking place beneath Grindavík. The town was evacuated again on March 31. Sigtryggsdottir is in Iceland and reports intense earthquake activity. There is rumbling from the ground, movement, and new fissures where lava may begin to flow out.

“It was also concerning when a volcanic fissure recently opened directly through and downstream of the barrier on the outskirts of Grindavík. Fortunately, it was just a brief eruption this time, and the lava did not cause any destruction,” she says.

The volcanic landscape is unpredictable. There are so many things that cannot be controlled.

“Much is unpredictable, such as how much time there is to warn people about the eruption, exactly where the volcanic fissure will open, how large it will be, how much lava will come, and how fast it will flow. The challenge is always having enough time to evacuate at-risk areas,” says Sigtryggsdottir.

Lava types behave differently

There are two main types of lava, which behave quite differently, and researchers never know which type will appear where.

Pahoehoe lava flows easily and tends to spread out in thin layers. It can accumulate in layers behind a defensive barrier until there is a risk of overtopping.

Less robust barriers can be used to divert or hold back pahoehoe lava compared to the more coarse and bulky block lava.

Bulldozer effect

Block lava moves more slowly and builds up beneath the solidifying crust.

Sigtryggsdottir compares it to a cream bun. The hot, sticky lava is like the cream inside the bun – until the top layer of hardened chocolate, or lava, is pushed upwards.

When block lava meets a barrier like an embankment dam, it is pushed upwards and can remain several metres above the top of the embankment. This increases the pressure, and eventually, the block lava can push the embankment dam away like a bulldozer.

“That's why block lava barriers must be extra strong and massive,” she explains.

Must believe protection is possible

But is it feasible to actually protect communities and infrastructure in Iceland against eruptions like those that have happened recently?

“Although there’s a lot of uncertainty regarding the development of the eruption itself, it's fully possible to delay and divert lava flows. There are many challenges, but civil society and infrastructure can be protected, and when we can, we must seize the opportunity and believe it will work,” she says.

Simulating changing terrain

Recording earthquakes and measuring movements in the Earth’s crust are important in Iceland. There are also computer simulations that show how lava flows move and spread.

Since the first eruption in 2021, researcher Hörn Hrafnsdottir has conducted simulations of lava flows and how they spread. These types of simulations must take many factors into account.

Researchers must input a lava source that flows with a certain volume per hour. Then the viscosity needs to be assessed, as this affects how far and how quickly the lava will flow. The simulation must also include information about the topography.

The latter is challenging because flowing and solidifying lava creates a new landscape and topography that must constantly be updated.

Safer volcanic communities

When asked whether the fieldwork from 2021 helps make Iceland – and other volcanic communities – safer, Sigtryggsdottir responds:

“Our work from 2021 showed that it was possible to delay and divert lava flows in the Reykjanes area. The barriers that my colleagues have subsequently built have made this even clearer. However, we cannot consider a protected area to be completely safe. Vulnerable areas must be evacuated regardless. The barriers protect houses and infrastructure if they are built high enough, as long as the volcanic fissures remain behind the barriers – so we can certainly say that our work contributes to safer volcanic communities.”

Reference:

Sigtryggsdóttir et al. Experience in diverting and containing lava flow by barriers constructed from in situ material during the 2021 Geldingardalir volcanic Eruption, Bulletin of Volcanology, vol. 87, 2025. DOI: 10.1007/s00445-025-01806-3

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

More content from NTNU:

-

Fish farming is least harmful to the seabed in the north

-

Study: Centralising hospitals has reduced birth mortality

-

Early testing of schoolchildren: “We found absolutely no effect”

-

This determines whether your income level rises or falls

-

Why is nothing being done about the destruction of nature?“We hand over the data, but then it stops there"

-

Researchers now know more about why quick clay is so unstable