This article was produced and financed by University of Bergen

Scientists discovered an ancient forefather

UiB scientists have found the lampshell’s ancient forefather, and discovered that the shells and bristles of the lampshells have a much older origin than priveously thought.

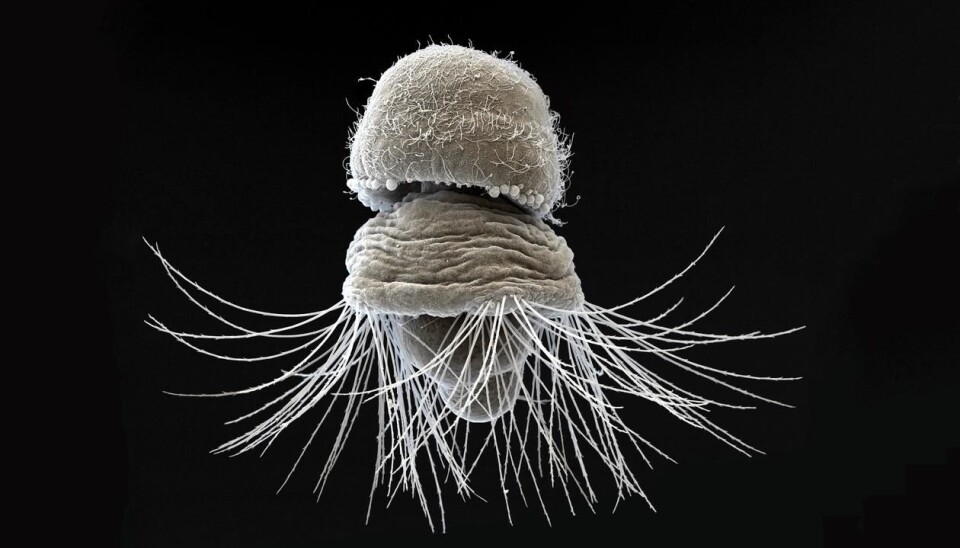

Brachiopods are marine animals that, at first glance, look like clams, but are in fact quite different anatomically. As larvae, they live a mobile life, swimming in cold waters. Upon metamorphosing into adults, their shells grow heavier and they attach themselves to the ocean bed, never to move again.

Now, scientists show the first molecular evidence that the hard tissues (chaetae and shells) of segmented worms, molluscs and brachiopods share a common origin that dates back to the Early Cambrian.

The results are published in the scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) by scientists from the Sars International Centre for Marine Molecular Biology at the University of Bergen (UiB).

Researching ancient genes

“You find shells like these from the Cambrian period, and they have not changed. We wanted to study a specific group of genes in the brachiopods,” says Andreas Hejnol, researcher at the Sars Centre.

By looking at HOX-genes, a group of related genes that pattern the basic structure and orientation of animals from head to tail, the scientists discovered that these genes also shape the shells and bristles.

Through examining brachiopods and their bristles, chaetae, the scientists discovered something new in the genes of the lampshells.

“We found amazing similiarities between the brachiopods, snails and segmented worms and their function of the HOX-genes,” the evolutionary biologist says.

Finding an ancient ancestor

The HOX genes control the brachiopods' shells and bristle during the development into the larva.

“We concluded that the brachiopods must be descendants of an ancient fossil that had both chaetae and shells,” says Hejnol.

The brachiopod forefather turned out to be the Wiwaxia, a 3-5 cm small animal living in the Cambrian time period, ca 500 million years ago.

"The Wiwaxia was covered in scales and had very large chaetae. This ancestor likely used already the Hox genes to model the bristles and shells in the brachiopods of our time, and it clearly places the Wiwaxia in a certain group of animals” says Hejnol.