An article from University of Tromsø – The Arctic University of Norway

The power of myths

Few things are as effective as a good myth when it comes to uniting a people or building a nation.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

The word “myth” often makes you think of dusty, ancient stories about gods and heroes. These were the stories people shared around the fire in the olden days, when they had neither decent TV entertainment nor scientific explanations for the mysteries of life.

Yet new myths emerge all the time, especially when it comes to our search for an identity as a people or a nation.

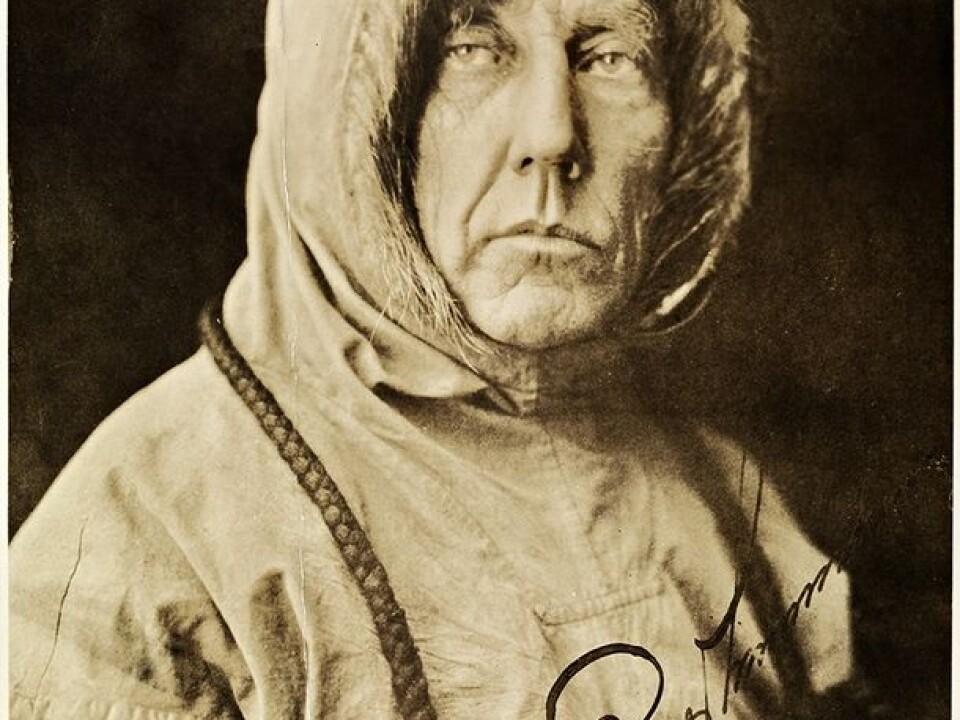

“Nation-building myths often develop in a time of crisis, for example if there is a war, or a period of great political or ideological upheaval,” says Roald E. Kristiansen, associate professor at the Department of History and Religious Studies at the University of Tromsø.

“After such a time of turmoil, it feels important to create unity and a national identity. There is a desire to create a future by looking back on past ideals. There will almost be a period of national romanticism, where the myths you share say something about who you wish to be as a people,” he says.

“True myths”

Kristiansen points out that it is irrelevant to think of myths as “true” in a scientific or historic context.

“However, they are ‘true’ to the extent that they contribute to realize the ideals they advocate,” he says.

Similarly, myths don’t always have to be supernatural fantasy stories. Sometimes myths are based on real people or events, where the stories eventually develop a mythical character.

Saint Olaf is an example of an historic person who appears in countless Norwegian myths. He is also an example of how much power myths can hold.

“Saint Olaf fought to gather and convert Norway under one king, and on the basis of one religion – Christianity. This was at a time of enormous ideological change. The Viking era was coming to an end, and the new Norway was emerging. Myths played a large role in determining which ideology would win the hearts and minds of the people,” says Kristiansen.

“Most people have heard the myth of how Saint Olaf’s hair and nails continued to grow after his death. This was considered by many as clear divine proof that he was right in his choice of religion. Christianity was introduced, and his grave in Nidaros became a popular pilgrimage for large parts of Western Europe,” he says.

Myths as an instrument of power

There are also many examples of how the contents of myths can be adapted to the needs of those in power.

When Snorre Sturlason wrote Norway’s national epic Heimskringla, it was very much to the benefit of the royal family of the day that their forefather Harald Hårfagre was portrayed as the first king of a united Norway.

“It might very well be that the Earls of Lade were more centrally placed in the power struggle that concluded with the gathering of Norway as one kingdom, but Harald Hårfagre fitted neatly in Snorre’s narrative. The contemporary kings could trace their lineage straight back to both Hårfagre and Saint Olav, and Hårfagre is, according to Heimskringla, a descendant of the Norse gods," says Kristiansen.

"Thus the myths legitimate the power of the king, who is also seen as a represent of God himself."

Getting rid of old myths is actually quite hard, and promoters of early Christianity were careful in relating the new religion to the old.

“Snorre would have regarded the Norse gods Tor and Odin more as historical figures, and would have portrayed them as subordinate to the Christian god. It wasn’t too important to Snorre to distinguish between real or mythical characters,” explains Kristiansen.

“Everything with a basis in reality had also some sort of religious meaning, which meant that the heroes of the Viking age were also connected to God even though they came along long before Christianity was introduced to the nation,” he says.

He explains that myths can develop both at the top of the power pyramid, and down among regular people. But for a myth to work, it needs to resonate with the masses. Myths that aren’t being retold will not live long.

Myths in a modern world

Today’s leaders also create myths about themselves. In modern terms, we might refer to it as image building. Totalitarian leaders can create pretty outrageous mythologies around their own personas, like Kim Jong-Il, for example, the previous leader of North Korea.

According to his official biography, Kim Jong-Il learnt to walk when he was only three weeks old, and started talking at eight weeks. While he was in university he supposedly authored 1500 books and six operas.

“He created a kind of communist religion around his own persona by constructing these myths. He’s the only arbiter of the eternal truth, and the only reason the stories aren’t dismissed as completely absurd, is that North Korea is a completely closed country,” the researcher points out.

But modern myths are also created in Norway. The German occupation during World War II was exactly such a time of upheaval where myths and national heroes were made. And the myths from this time continue to thrive among Norwegians of today.

“For instance, look at the recent film about Max Manus, a resistance hero. This can be seen as a typical modern myth construction. Just because something is a myth, doesn’t necessarily mean it is untrue. But we go back in time searching for the most coveted ideals we can build on, and thus create a world based on the values we find to be the most important”.

--------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no