An article from University of Tromsø – The Arctic University of Norway

Polar widows

Being a polar explorer was extremely hard work, but it was certainly no bed of roses too for the explorer's wife. Sometimes it could take several years before she saw her husband again.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

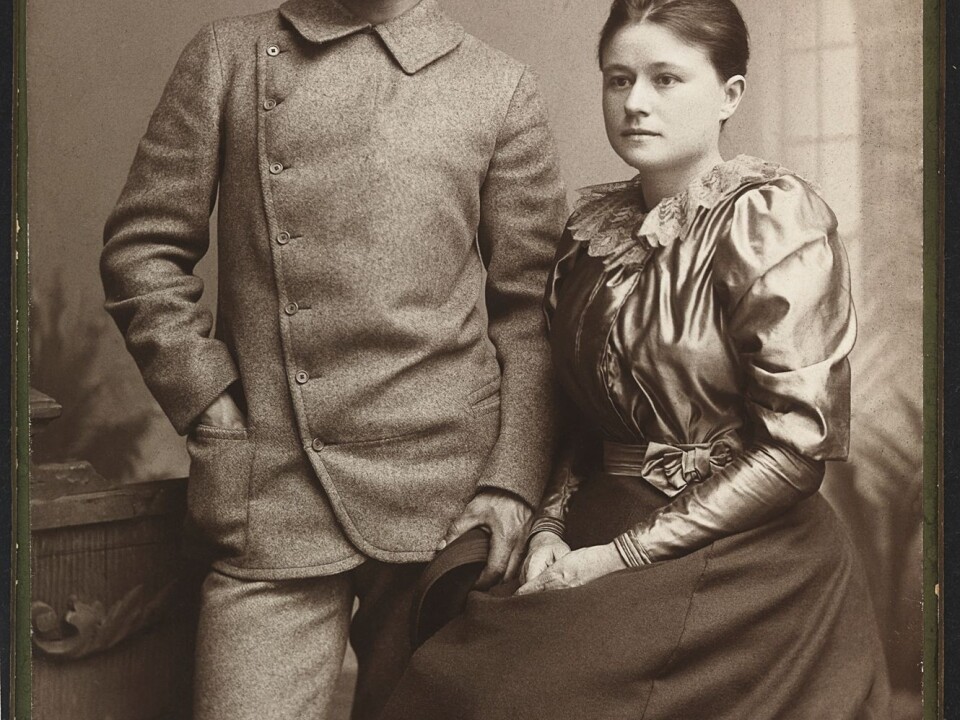

"In the middle of March, I went ashore in Tromsø to be home for a fortnight. At home, there had come a little son. Then I had to say goodbye to my boy and wife, and head out on a journey that was planned to last for two to three years, but that would last for nearly four years."

With these words, Helmer Julius Hanssen described his "family life" with his wife Kristine Augusta before heading out on an expedition to the Northwest Passage in 1903.

He accompanied the Norwegian polar explorer Roald Amundsen through both the Northwest and Northeast Passages, as well as on the famous South Pole expedition.

But his life as an explorer had a downside, as he had to endure long periods without contact with his wife and children.

"Based on what he says, you might think that Hanssen is without emotions, but I rather think he has developed some emotional distance from his family,” says Mary Anne Hauan, director of the University of Tromsø Museum.

“Otherwise, his separation from his family would be too much to bear," she adds.

Used to absent males

We know more about what it was like for polar explorers on their expeditions, and their longing and loss, than we know about what it was like for their families to be without a husband and father for so long.

"Yes, and there were many who were gone for a long time,” says polar historian Harald Dag Jølle.

He mentions Helmer Hanssen and Otto Sverdrup who went across the Arctic Ocean for three years (1893-1896) and then for another four years (1898-1902).

"It can sometimes be as crushing hard on me, especially when I think about those who are at home, who are sitting and waiting and know nothing about us. Likewise, when one comes to think about whether we will be forced to stay here another winter, one cannot disregard the possibility."

Thus wrote Otto Sverdrup himself on his second Fram expedition, of which he was the leader.

The initial plan was to stay for three winter seasons. But because they were still stuck in the ice in the summer of 1901, he and his crew had to overwinter in the Arctic yet another year.

Jølle says that polar explorers were paid wages, so from a financial perspective, their families managed well.

“Otto Sverdrup renegotiated his wages when he got married. His wife Gretha had to depend on his income when he was travelling.”

This was a time when many families had to survive long periods without a husband and father.

According to Hauan, coastal women were accustomed to their men being absent, because of their work as traders and as fishermen. They were also well acquainted with the risks to which the men were exposed.

“Polar explorers first had to cross a large ocean, and then their boats would be frozen into the ice. If you got scurvy or were seriously injured, that was your fate,” she says. “To avoid having to worry all the time, I think the women developed a displacement mechanism.”

Courage − and not just the men

Fridtjof Nansen's book, Farthest North, contains the following dedication: "To her who christened the ship, and had the courage to remain behind."

By "her", Nansen meant his wife, Eva.

This dedication shows that the explorer realized that it was not only him who had to be abundantly equipped with courage. The same was also true of his wife, who took care of the family alone.

Eva Helene Sars Nansen (1859-1907) was an internationally known singer before she met Fridtjof Nansen on a cross-country ski trail in 1888. She grew up with her parents who raised her to be a strong and independent woman.

During the first years of their marriage, Nansen was crazy with longing for her. But that changed with the years.

She remained his safe haven, but he was a hunter and kept coming back to the expression that "happiness is where you are not."

Died alone

"Oh, the times I have longed so much and it has been so empty here, but you can't think I'm so awful that I for a single second thought it was wrong of you that you went, well I'm an unpardonable egotist, but you shouldn't make me into something that I am not either."

Thus writes a smug Fridtjof to Eva in 1896. He has just returned home after three years frozen in the ice with their ship. And now he has been so generous as to allow his Eva to go on a three-week concert tour to Sweden and Finland.

"Nansen spent almost his entire life travelling. He was also a diplomat in London. His absence certainly had some effect on his marriage,” says Jølle.

Moreover, he was a superstar in his time, and that took up space in its way.

Eva Nansen died on 9 December 1907 of pneumonia, aged 49. Her husband was not present.

Letters from the explorers

"And then comes the question sometimes as to whether you really do not miss much by spending so much of your short life on the ice and under these conditions." (Hjalmar Riiser-Larsen 1930)

"Women's day. Yes, none of us miss them a great deal, but out of habit there is much talk about them, and they do often best at a distance." (Sverre (24), Karl (28) and August (31), overwintered at Hopen 1923-1924)

"I can not participate in my children's celebrations. Edit and Martha were confirmed while I was gone. Elsie will marry this year while I have voluntarily spent two years in exile." (Bernhard Eilertsen, working at the Leith Harbour whaling station on South Georgia Island, 1930)

Attacks of rage and alcohol abuse

Hilda Johansen was able to handle her husband's long absences. It was when he was at home that things got out of hand.

"The worst was at night, the cold, dark winter nights. He chased me around in my nightclothes, around the house all night, while he constantly showered me with insults and angry reproaches ... When, as he did several times, he took me by the throat and with teeth-gnashing fury declared that it would be a joy to strangle me, then I thought I would die.”

Thus wrote Hilda Johansen (1868 - 1956) in a letter to the courts in 1906. She wants a divorce. Her husband, the Arctic explorer Fredrik Hjalmar Johansen, struggled with extensive alcohol abuse.

The abuse had begun in earnest when they moved to the north in 1901 after he was appointed a company commander in the Army. The rages then came more often, and he struck her with either his bare hands or with objects he found nearby:

"He emptied the water jug's contents over me several times, and threw different things at me − bottles, glasses, candlesticks with lighted candles, and often burning lamps. He always threw things with a great deal of force. My husband is very strong."

Took his own life

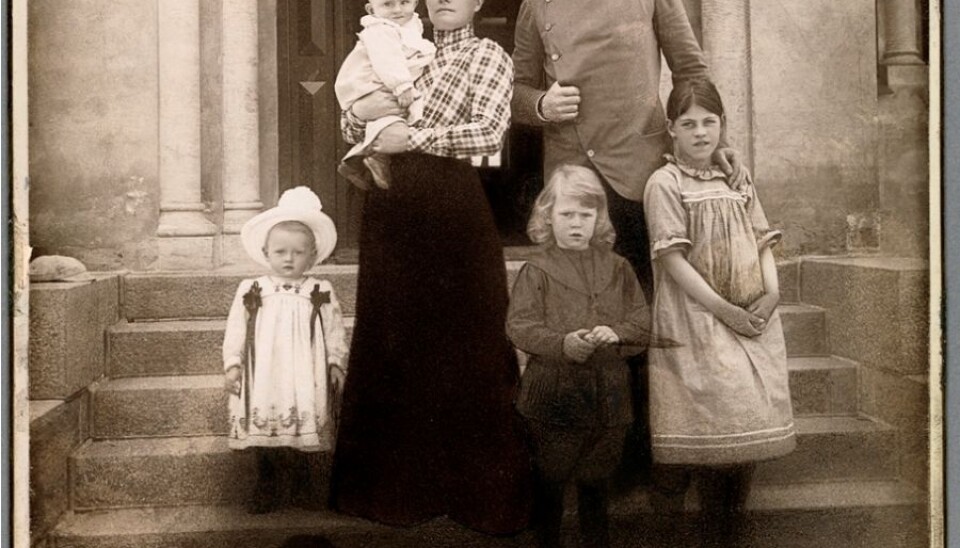

Fredrik Hjalmar Johansen (1867-1913) found his way into Norway's history books by participating in Nansen's Fram expedition and Roald Amundsen's South Pole expedition. Even though he helped save the lives of his superiors, fame eluded him, and he found himself in the shadows.

After seeing his family life, his career and finances go to ruin, Hjalmar Johansen took his own life in 1913.

His wife was then left to take care of their four children alone. Despite this, all her children passed their upper secondary school exams, which was quite uncommon for that time.

Fred Johansen, grandson of Hjalmar and Hilda, said that Hilda was doubtless a strong woman.

He remembers her as a unique combination of dignity and determination, but at the same time with a gentleness that was out of the ordinary.

"I have only fond memories of my grandmother, but it's not until my adulthood that I have understood what she went through to help her children grow to adulthood," he says.

"The sun of my life"

Despite all the struggles in his grandparents' marriage, Fred Johansen is convinced that the two were very fond of each other.

He said that Hilda’s long letters, which waited for Hjalmar both in Madeira on the way south, and in Tasmania on the way north, tell him that he still played a big role in her life.

“And he called her 'the sun of my life' in the last letter I have found between the two - before he shot himself. There was no other person for them.”

Hilda Johansen was also the first female in the nation to have a job at the Norwegian National Bank, which happened with Fridtjof Nansen's help. But it is also how she managed to support her family after her husband's death.

"My grandmother's efforts in the 'home front' were on the same order of magnitude as the challenges my grandfather faced on the ice," says Fred Johansen.

Sources: The Norwegian Encyclopaedia, Fred Johansen: Hilda and Hers, 2009, Norwegian Polar History, Per-Egil Hegge: Just one will.

-------------------------------------------