This article was produced and financed by The Fram Centre

Looking for answers from indigenous peoples on the tundra

What happens when indigenous peoples are exposed to globalisation and assimilation? Is it possible for them to maintain their cultural heritage and continue with their traditional way of life? Zoia Vylka Ravna went to the Nenets on the Russian tundra in search of answers.

“The choices you make have enormous impact on your way of life. Will you live in a traditional “chum” or a house? Will you get around by car or by reindeer and sledge?” These questions come from Zoia Vylka Ravna.

She is a PhD student at NIKU – the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research at the Fram Centre in Tromsø. For her doctoral project at UiT The Arctic University of Norway, she is looking into how globalisation affects indigenous people.

Her fieldwork has been done among the Nenets. There are almost 45 000 people who can call themselves Nenets. Like the other 45 or so indigenous peoples in Russia, the Nenets still live off what nature provides, reindeer husbandry, and fishing.

They live in eastern Russia, Siberia, and northwestern Russia. For her studies, Ravna went to the northwestern area, to the Yamal Peninsula, which extends 700 km into the Barents Sea.

Unique culture

“The Nenets are nomads who have had a unique way of life. The reindeer is central to the Nenets’ culture. Without it, they would disappear as an indigenous people. They are born into a culture where traditional knowledge must be passed down from person to person if the community is to survive”, says Ravna.

But the Russian education system requires the children of nomads to leave their camps and live at boarding schools for nine months a year. This means that young people have little time to acquire traditional knowledge, language, and spiritual values.

Among the Nenets, women are the custodians of traditional knowledge, and it is women who pass it on to small children. When the women leave the camps and move to villages and towns – voluntarily or because they have no other option – they set an example for young girls, who may also leave the traditional life on the tundra.

The reindeer herder is left behind: a man who struggles to find a mate. There is an increasing tendency that young women choose not to return to the nomadic life on the tundra after finishing their schooling.

Conversely, young men more often return to the tundra and try to carry on with life as before without taking into consideration that there is a need to change their way of thinking. In addition we see that men’s life expectancy is short, partly because of heavy alcohol consumption, which adds to the problem.

On the tundra

Ravna has spent long periods on the tundra with the Nenets to understand their way of thinking. The objective of the research project is to develop a framework that allows the Russian education system and the Nenets’ nomadic life adapt to each other.

“We have to go back to the formation of the Soviet Union to find the background for what is happening now. Before the Russian Revolution, the Nenets led a traditional nomadic life based on reindeer husbandry”, says Ravna.

One of the aims of the Soviet state was to create an egalitarian society without gender restrictions, and this shook up the traditional gender roles of the nomads. The other major change came with the Soviet system of agricultural collectives: reindeer were collectivised, though reindeer had never been collective property historically.

The period from 1920 to 1950 brought many changes that affected the transmission of traditional knowledge. One such change was forced relocation to larger villages because of the establishment of large collectives.

“It’s still difficult for the Russian system to understand the perspective of indigenous people, which is often based on seemingly abstract ideas”, says Ravna.

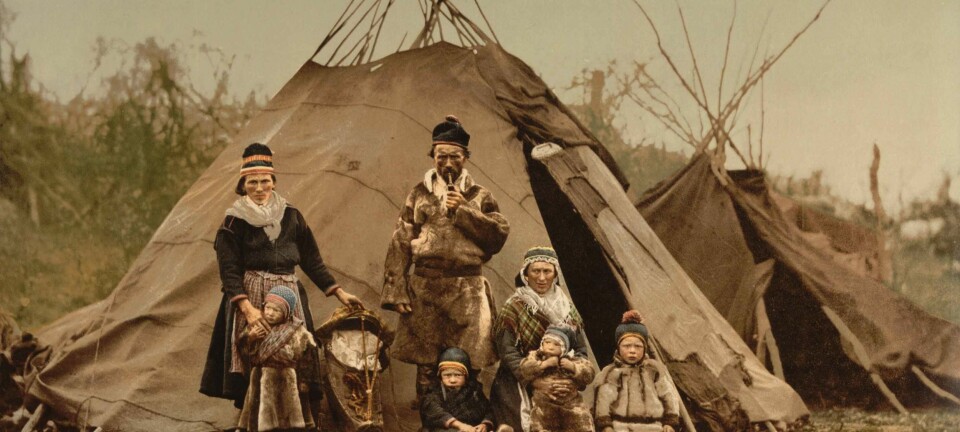

“This is something we see in other parts of the world; the wider society has trouble understanding indigenous communities. When they encounter something they don’t understand they try to control it through rules and regulations. The Norwegianisation of the Sami people serves as a good example”, says Ravna.

Personal experience

In part, she uses her own cultural background to understand what is happening. Ravna is herself a Nenets and grew up in the Nenets autonomous region in the village of Krasnoje.

In 1993, she moved to St. Petersburg to study history and culturology and shared student housing with many other students from various parts of northern Russia, Siberia, and the Far East.

“Yes, I suppose you could say I’m doing research into myself. But I think that’s necessary to create a comprehensive picture of a long-term process such as the education of a nomad child – which should include the teaching of indigenous values and knowledge. That doesn’t mean that researchers with a different background can’t study the Nenets, but research should be done on a foundation of knowledge of their history. There’s a need to change focus from regarding the traditional culture of nomads as difficult, outdated, and impractical, to looking at the advantages instead."

“The Nenets’ way of life is complex but characterised by flexibility. They are able to adapt and are mobile. Their culture can provide people with new types of solutions, solutions modern-day research can’t help us find”, says Ravna.

No right answers

There is no single “right” way to hand down traditional knowledge, but Ravna believes we need new methods of transmitting traditional culture from generation to generation.

“In a classroom, you’re expected to acquire knowledge that makes you an efficient employee: a producer of material values. For the nomads, other values are important, such as living in harmony with nature and with other ethnic groups.

“Increased globalisation can have irreversible consequences for Nenets culture. The Nenets realise this, and at the same time they realise that they need outside help to adapt to this development. Still, the Nenets’ knowledge is unique and must be their most important tool when adapting to a rapidly changing world”, says Ravna.