THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY Oslo Metropolitan University - read more

Education is no guarantee against unemployment and poverty

Despite the population's increasing educational level, the risk of becoming unemployed or becoming a social assistance or disability benefit recipient is not decreasing correspondingly, according to new research.

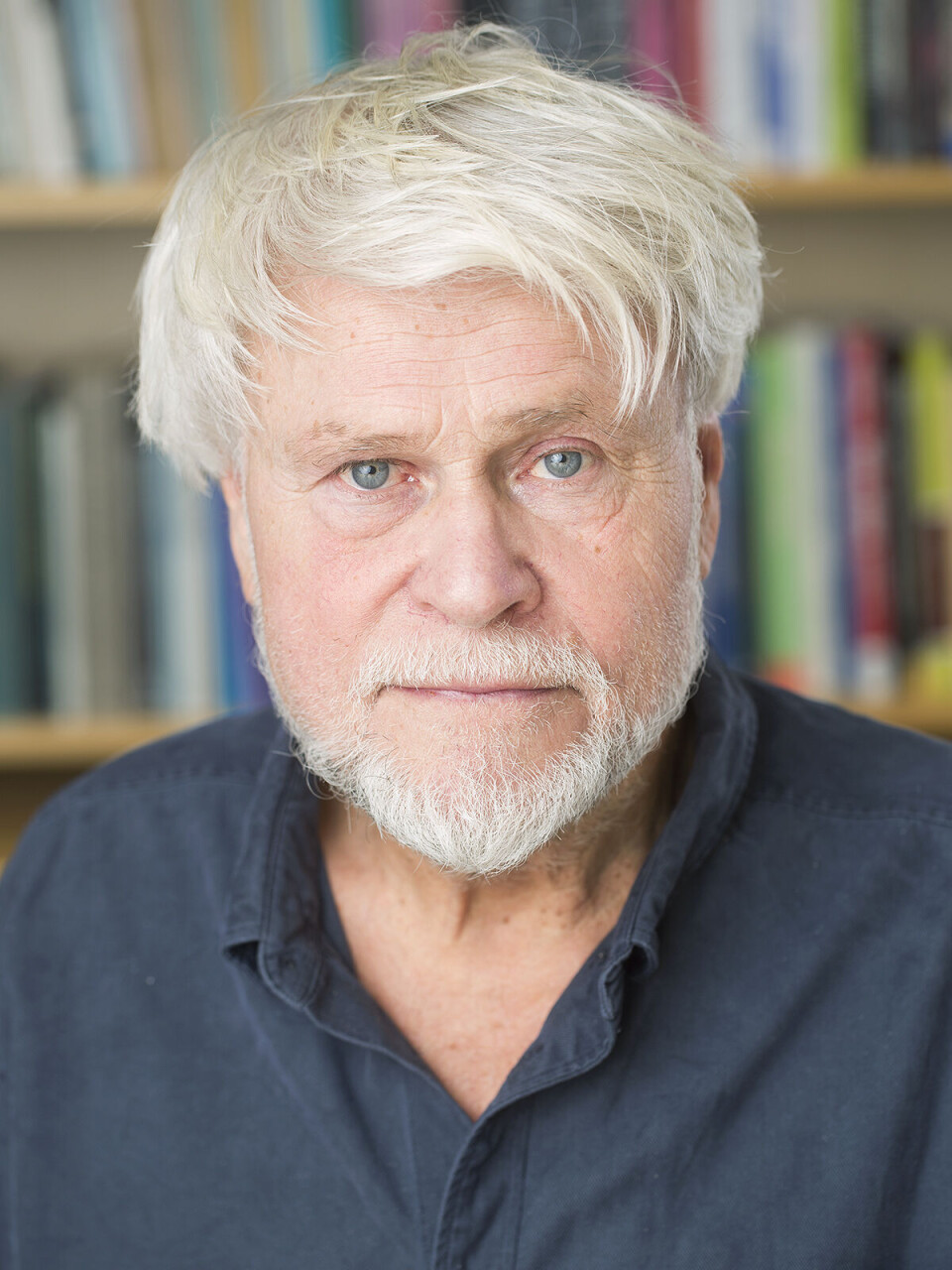

"This is a paradox in many ways, because many people will think that an increase in the educational level will reduce the risk of such outcomes," says Jon Ivar Elstad, a researcher at NOVA (Norwegian Social Research) at OsloMet.

A high educational level does not protect the whole cohort

Elstad has compared six birth cohorts, the first born around 1955 and the last around 1980, and has found that the risk of becoming unemployed, receiving disability benefit or social assistance by the age of 35 was roughly the same in all the birth cohorts. This is despite the fact that the educational level was significantly higher for the 1980 cohort than among those born earlier.

"Of course, this does not mean that education is of no significance," he says, adding that education is often regarded as a good guarantee against unemployment and poverty. The statistics indicate that it is those with least education who experience the biggest problems in the labour market.

What the NOVA study shows, however, is that the average educational level in a birth cohort has not made much difference to how often the birth cohort overall has experienced unemployment or other forms of economic marginalisation. A collective higher educational level will not protect a generation or a birth cohort against economic marginalisation, Elstad emphasises.

The risk has not changed

Within each birth cohort, it is nonetheless clear that the individual’s educational level is strongly linked to the risk of economic marginalisation.

"Those who only have primary/lower secondary education, for example, are more often unemployed or recipients of social assistance or disability benefit," he says, adding that these differences have grown over time. "As the number of those with little education has decreased, the gap to the rest of the population has increased in several areas."

A surprising finding

Another finding from the study, which Elstad describes in an article in the book ‘Generational Tensions and Solidarity within Advanced Welfare States’, is how the composition of the economically marginalised group has changed in recent decades.

"It is a surprising finding that the economically marginalised group increasingly comprise people with more than just lower secondary education," he says.

In 1990, for example, few of the 35-year-olds who received social assistance had an education: 90 per cent of them had no education beyond lower secondary school. In 2015, by comparison, at least 30 per cent of them had at least an upper secondary education.

The researcher found similar findings as regards unemployment. In 1990, three out of four unemployed people had lower secondary school as their highest education, while in 2015, the proportion had decreased to a quarter, and three out of four unemployed people had either upper secondary or higher education, according to the study.

"Previously, it was those with only lower secondary education who dominated among the economically marginalised. As the educational level has increased, the proportion of well-educated people among the economically marginalised has steadily increased," Elstad comments.

Tough competition is one possible explanation

One explanation is that the explosive growth in education in recent years has led to a university college or university education no longer being something unique. It is therefore no longer an automatic admission ticket to a secure and good position in today’s labour market.

"The competition is tough in many sectors that employ qualified labour. This means that some people with higher education have to make do with insecure jobs, short-term contracts and an unstable income. Some of them are also pushed further down the occupational hierarchy," he says and continues:

"Educational qualifications are thus no guarantee of a successful career, and, for some, the outcome could even be economic marginalisation."

Warns against putting too much faith in mass education

Elstad says that other studies conducted abroad have identified tendencies that are similar to those he himself has found, i.e., that a higher educational level in the population does not in itself lead to lower unemployment, less exclusion from the labour market, reduced economic marginalisation or greater social equality.

At the same time, he points out that a higher educational level undoubtedly has many positive aspects, including a higher material standard of living and better public health.

"It is easy to understand why people advocate more education, of course. Parents know that their children’s opportunities will improve if they have a university or university college education. Employees know that it is good to be able to refer to exam passes, courses and supplementary education in wage negotiations," Elstad says.

He nonetheless warns both politicians and the general public against believing that education – and even more education – will solve all the problems society is facing.

"When politicians see that those without upper secondary education are particularly at risk of economic marginalisation, it is easy to believe that the solution must be that everyone completes upper secondary school. And even though the desire for more education can be 'smart' at the individual level, it is not necessarily 'smart' for society as a whole," he says.

Could be dysfunctional for society

If the drive for education is primarily about improving individuals’ chances in competition with others, this could be dysfunctional for society, he argues, illustrating his point as follows:

"Imagine a football ground where all the spectators are seated and can see pretty well. But if one spectator stands up to see even better, more and more spectators will stand up, with the result that all the spectators have to stand, but they won’t see any better than they did when everyone was seated."

At the same time, Elstad adds that what he says should not be taken as a general criticism of the educational system, or as a warning against taking advantage of educational opportunities.

"But it is important that possible negative aspects of the explosive growth in education are not ignored," he says.

Reference:

Elstad, J.I. (2021). Will more education work? Economic marginalization and educational inequalities across birth cohorts 1955–1980. In Falch-Eriksen, A., Takle, M. & Slagsvold, B. (eds.): Generational Tensions and Solidarity Within Advanced Welfare States (routledge.com).

See more content from OsloMet:

-

The mural in Oslo City Hall conceals a dramatic story – about the artist’s own life

-

Mental health problems are widespread among Ukrainian refugees

-

Only 1 in 10 Ukrainians want to return

-

How class divisions are maintained in Norway

-

Many adolescents think they're not interested in politics – until a teacher gets them to reflect on their own lives

-

Researcher: Local government was key to managing the pandemic