This article was produced and financed by Diku - The Norwegian Agency for International Cooperation and Quality Enhancement in Higher Education

Teaching children in their mother tongue in Mozambique

Portuguese is the language of instruction in all schools in Mozambique, although most children don’t understand it when they start school. This is now about to change.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Children in Mozambique start school without knowing Portuguese, yet they have to learn everything in Portuguese.

"This makes the learning process very difficult. Everything we learn, we learn through language,” says Professor Armindo Ngunga at Eduardo Mondlane University (UEM) in Maputo, Mozambique.

Results from pilot projects on mother tongue education in Mozambique show that children who are taught in their mother tongue do better in school than those who are taught in Portuguese.

40 per cent of the population speak Portuguese - hardly anyone as their mother tongue.

Pressure for bilingual education

Research results by Ngunga and his colleagues have contributed to recent change in Mozambique. There is an emerging interest in bilingual education at grassroots level; more parents now want their children’s education to be conducted in their mother tongue in the first years of primary school. This again has resulted in governmental demands for the production of grammars, orthographies and dictionaries.

Ngunga is head of the Center for African Studies at the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at UEM, and coordinates the research project Standardization and Harmonization of Cross-border Languages. The long-term aim of the project is a transformation of the educational system from a Portuguese school to a mother tongue school.

The project is a collaboration with the University of Oslo and the University of Zimbabwe and is supported by The Norwegian Programme for Development, Research and Education (NUFU).

Languages without borders

Historically Mozambique and Zimbabwe have shared several spoken languages. But as time, colonial powers and political changes have come and gone, the languages have drifted apart.

Sena, Changana and Shona are all linguistically related Bantu languages, all spoken in Mozambique and Zimbabwe. Shona is spoken in Botswana as well, whereas Changana and Sena are also spoken in South Africa and Malawi.

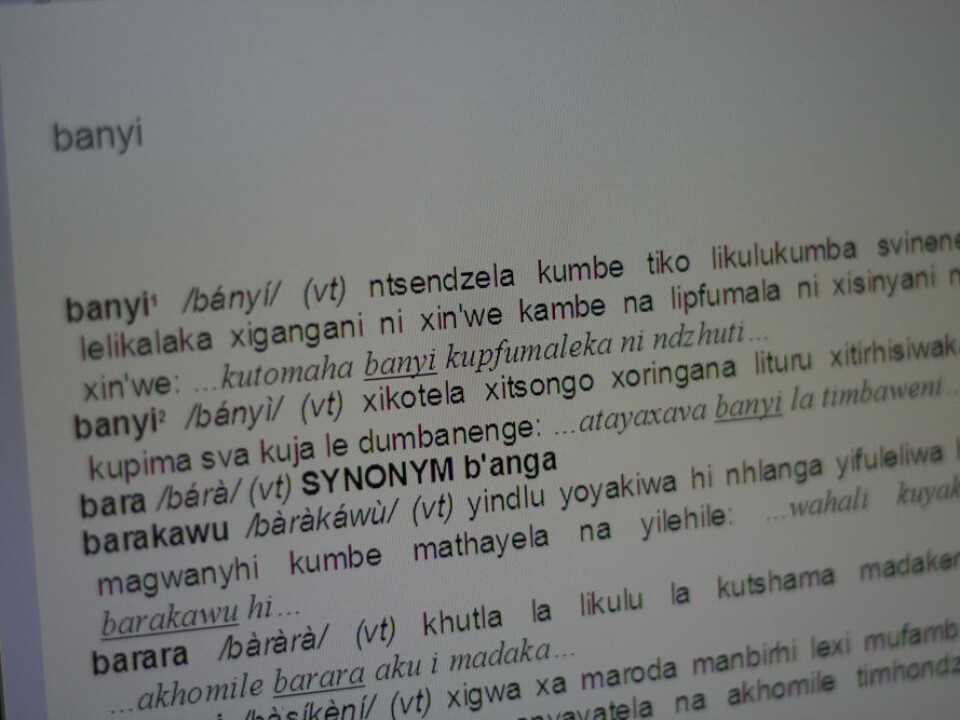

The researchers want to re-establish the close relationship of the languages by harmonizing their orthographies – their spelling and language norms. To do this they need, as a first step, to go out and record spoken languages. This work is done mostly by students. In addition they collect text samples.

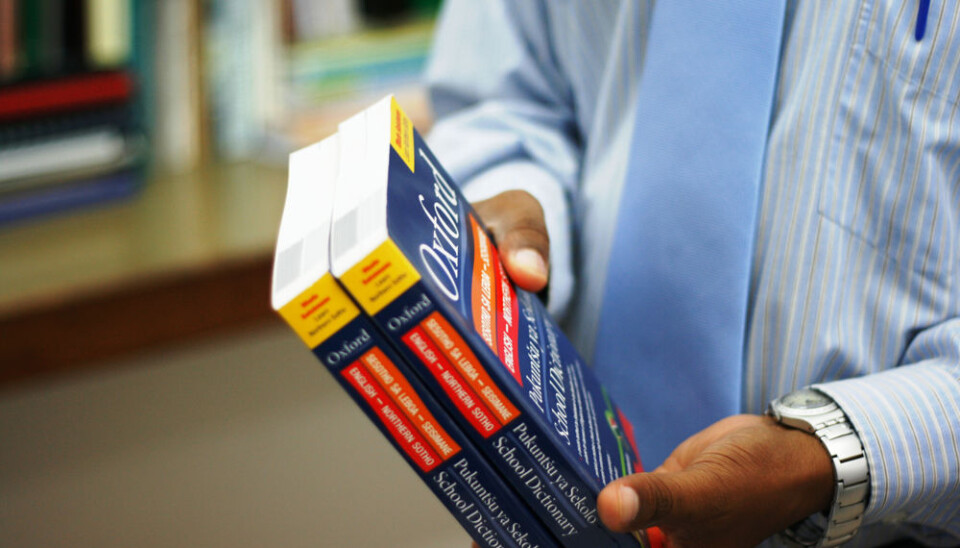

The next step is to do transcriptions of the oral material and scan the written texts before transferring all the data into a database from which they are now producing grammars and dictionaries. These new language tools are of vital importance.

Mother tongue pioneers

Historically, local African languages have been written down by a wide range of people, missionaries for instance. Different people have documented different languages according to their own mother tongue’s orthography. In Mozambique this has resulted in the same language having developed three or four parallel writing systems.

“What are the necessary steps forward to develop adequate language systems?”

“First of all, it is important to standardise the writing system so that it can be used in schools. Secondly, we need a standard terminology to be used in schools,” says Professor Ngunga.

The teachers who are taking part in the pilot projects on mother tongue education did not learn their own mother tongue in school; they are in a sense learning it at the same time as they teach. In this perspective they are mother tongue pioneers.

“The grammar and the dictionaries are going to be instrumental to the success of this project,” Professor Ngunga emphasises.

Same but different

In Zimbabwe, a former British colony, the language situation is completely different from Mozambique. The native languages have been the educational languages for decades. The British colonial powers brought their strong academic traditions to Zimbabwe. In Mozambique the universities are still relatively young due to the Portuguese rulers’ lack of academic aspirations for their colony.

“We have a language policy for the language curriculum in Zimbabwe. The mother tongue is supposed to be taught in primary school for the first three grades. This year it was set for an exam for another minority language called Tonga for the first time. I think it is a positive move from the government towards developing the languages,” explains research fellow Dr. Nomalanga Mpofu.

Regional cooperation

“Cooperation between the African institutions is very important if we want to proceed in our development together. The development and cooperation at grassroots level is done through the languages that people speak. We share the same border, the same language and people cooperate at this level. On a governmental level they speak English and Portuguese. It is important that we develop the languages that we use in order to make better use of common resources,” says professor Ngunga.

The researcher’s efforts are already producing results. The Minister of Culture in Mozambique wanted to see the orthography report before the Parliament passed a law on the official orthography of Mozambique. The new law is an indirect effect of the project.

“Could mother tongues become languages of instruction in higher education institutions in Mozambique?”

“At Eduardo Mondlane University, I think it will happen, yes,” Professor Ngunga concludes optimistically.