An article from Oslo University Hospital

Old patient stories help computers to predict cancer

Old paper records of Norwegian prostate patients from the archives of a 80-year-old Norwegian clinician, will now play a surprisingly crucial role in developing future machine learning methods for cancer prognosis.

In near future computers will learn to recognize cancer. To achieve this they will need huge amounts of patient data. Prostate cancer is the most common cancer among Norwegian men. Fortunately, not everybody becomes ill or develops cancer.

When something in the body can develop into cancer, it is natural that we will wish to remove it. Surgery, however, is not always the right solution.

The tools we have today that help us distinguish between patients with dangerous and less dangerous cancer are not precise and efficient enough. Troublesome side effects such as impotence and incontinence are common for those who undergo surgery.

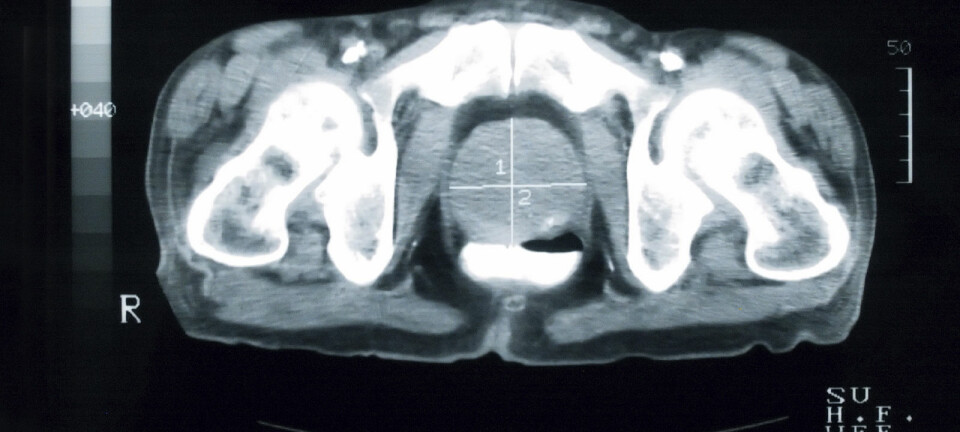

When a doctor suspects cancer somewhere in the body of a patient, he or she takes a sample of the tissue to provide an answer. However, tissue samples may remain on hold for up to two months in Norway, due to the lack of medical specialists who can diagnose cancer. Most health systems in the world are in the same situation.

The research project DoMore! at the Oslo University Hospital aims to automate this task. Recent advances in computer power and processing have made it possible to explore far greater amounts of data than before. with the help of tools like Deep Learning, Big Data, texture analysis and quantification of DNA.

This is done by using vast reserves of hospital patient data to find patterns that tell something about a patient's cancer and the likely outcome - the prognosis. The goal is to radically improve prognostication of cancer by using digital tools in pathology.

By feeding computers with vast amounts of data, computers can be trained to recognize patterns. By comparing images from a large number of patients, computers will be able to learn how to distinguish between dangerous and less dangerous cancer.

But where can we get access to the amounts of data the computers need to discover these patterns?

50 years of data

As a specialist in both surgery and urology, Håkon Wæhre (80) has been following patients with prostate cancer for more than 50 years. As a newly-trained surgeon, Wæhre became aware of the plagues the patients received after being used for prostate cancer. His efforts for protecting "the men's abdomens, has since been a red thread throughout his career.

Now, parts of his clinical data archives are included in DoMore!

The researchers at the Department of Cancer Genetics and Informatics at Oslo University Hospital use the data he collected to train computers to recognize cancer faster and more accurate than what the specialists are capable of with the naked eye:

Samples and information from 317 patients between 40 and 74 years treated for prostate cancer at The Norwegian Radium Hospital in Oslo between 1987 and 2004 are now used to develop computer technology that can prognosticate - predict - cancer development in patients. The use of the data is approved by the The Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics and the patients themselves.

"It is so important that your abdomen works. When damaged, it creates more significant consequences that are not commonly talked about. It affects not only the man but also the partner and everyone else around him," says Wæhre.

"Until we find better solutions to predict how cancer develops, many prostate patients will continue to be overtreated," he continues.

Looking for patterns

It was as a graduate physician in Trondheim in the early 1960s that Wæhre first came into contact with patients with urologic cancer - prostate cancer, bladder cancer and testicular cancer. The hospital's choices of treatment were often random.

"We had so little to offer. All we could do was to remove everything. The consequences for the patients were cruel - impotence, infertility, incontinence and problems urinating, often from a young age," says Wæhre.

The patients' situation made the graduate surgeon interested in looking for patterns among the cancer cases in hopes of finding answers to their treatment needs. His colleagues were impressed. How had he found so many patients in the same category?

"I started using 'the scientific needle'," Wæhre says. He recorded the patient information by stamping holes in punch cards. When inserting a knitting needle through the holes, he could see which patients cards fell out of the pile and which ones were left behind. That way he could find groups of patients with characteristic traits. The alternative had been to read through hundreds of records.

"I did not know how to use the information, just that it could be useful," says Wæhre about the beginning of fifty years of data collection.

"I could not foresee what opportunities patient data would create for diagnosis and prognostics through automation. Nevertheless, I see now that we are getting the tools I was hoping for."

Karolina Cyll is a fellow at the Department of Cancer Genetics and Informatics and works with Wæhres material.

"His data is particularly valuable because many of the patients have been followed up until their death. The data also include patients from before clinicians started using the blood sample PSA measurement that detects very early signs of cancer. Many of the cases have therefore come far beyond what is typical of today's patients, which is essential in understanding what direction cancer will take already from an early stage," says Cyll.

Major social problems

"Håkon and his database has played a crucial role in our research. The quality of a research group like our is entirely dependent on the fact that clinicians with heavy patient experience participate, collect, and quality assures clinical information," says Håvard Danielsen, director of The Institute for Cancer Genetics and Informatics and leader for DoMore!

The goal for the researchers is to provide faster and safer systems for prognosis of cancer by 2021.